Tens of thousands of migrants marching, on foot, coming from all over Central America, and especially from El Salvador, and wanting to enter the United States to attend the great Summit organised by Joe Biden: not as diplomatic guests, but as a desperate mass in search of peace, food, work. A powerful march, which obviously ended up against the concrete wall, barbed wire and border guards: the symbol of the failure of a Summit that was probably a propaganda move for internal purposes, and only served to show America’s inability to sustain a positive role on the continent.

At the border, the army is waiting to repel them. The few who manage to enter, and are condemned to live as illegal immigrants in a land whose language they do not even understand, are enlisted by the same criminal gangs that oppressed them in their homeland, or are martyred with demands for money, violence, and rape. The American federal administration, instead of fighting the phenomenon, uses it to defend insane laws that arm citizens: let everyone buy a machine gun and finally learn to defend themselves.

The reason for the Summit

From 8 to 10 June 2022, the ‘Summit of the Americas’ was held in Los Angeles, a meeting marred by vetoes, controversy, disorganisation, defections, and which produced little: a disaster of image and political substance. The earthquake was triggered by Biden even before it began: despite the fact that the White House had hoped for the participation of the leaders of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela[1], the decision was revoked – because, as spokeswoman Karine Jean-Pierre explained, ‘dictators should not be invited’[2]. The reasons jar with what had happened just a month earlier, when Biden himself hosted the US-ASEAN Summit attended by Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos – openly authoritarian regimes – excluding only Myanmar[3].

It is clear to all that there are electoral needs behind it: Biden needs to strengthen the bond with expatriate Latinos in America, who are hostile to South American governments. Moreover, the excluded states are those that have the strongest relations with Russia and China. The first reaction is from Mexican President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, who announces his defection in protest against the exclusion of the three countries[4]. He receives the support of Maduro, who calls Biden’s “an act of discrimination”[5]. Bolivian President Luis Arce threatens to boycott the meeting, Chilean President Gabriel Boric speaks of a ‘grave mistake’[6]. and his Argentinean counterpart, Alberto Fernández, shares his opinion. For Cuba it is ‘an unjustified move’ and Ralph Gonsalves, the Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, accuses Washington of ‘using bad manners’[7].

Particularly catastrophic was the decision by the President of Honduras, Xiomara Castro, to boycott the summit, given that until a few days before, he had been maintaining intense diplomatic relations with Kamala Harris, planning important cooperation initiatives[8]. The Nicaraguan Daniel Ortega renounced the summit with words of contempt[9], and the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, also announced that he would boycott the summit[10]: this means that an important demarcation line has been crossed and that the USA has lost that charisma of a great power that until a few years ago few South American countries allowed themselves to openly contest.

The USA is going through a very difficult phase, both because of the pandemic, which has exhausted the country, and because of the battles over abortion and arms sales. Inflation gallops and reaches record levels, the long shadow of the 2020 elections is still at the centre of a fierce debate, politics is divided on climate change, but above all on the Ukrainian crisis. Never before has the current president had such a low approval rating[11]. Hence the choice to tackle an ancient and controversial topic: immigration from the southern regions. And this is, of course, the central theme of the summit.

The march of the Latinos

14,000 march together to the United States a few days before the Summit of the Americas[12]

Further agitating the climate are 14,000 people who organise themselves for a mass migration just days before the start of the summit. From Tapachula, a small town on the border between Guatemala and Mexico, they set off northwards, walking almost 2000 kilometres, in order to reach the Californian border and cross it. Among them are entire families, 3,000 children, at least 126 pregnant women and more than 70 physically disabled people[13].

Tapachula has about 350,000 inhabitants, but has long been home to several thousand more, having become, along with Tenosique in Tabasco, a hub for migrants trapped by the repression of migration flows from Central America. The town is located in Chapas, one of Mexico’s poorest states, and is a sort of displaced persons camp for migrants, who stay here for several months, waiting for a visa that may never arrive[14]. An open-air prison where despair, misery and anger are the companions of those who hoped for a better life than the one they left behind.

Migrants come from Honduras, El Salvador, Haiti, Venezuela, others from much further afield: Cuba, Brazil, Nigeria, Palestine and, recently, even Ukraine. They flee war, hunger, torture[15]. The journey to Tapachula takes months, during which they fight for survival[16]. The disappointment of those who have come this far and find that they cannot go on is great, anger and frustration run rampant. The number of migrants crossing the southern border with Mexico is steadily increasing[17]: every year at least half a million people attempt the journey to the United States, and most of these come from the three northern triangle countries, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Of these, only a small proportion require visas[18]. According to the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), in 2021 there were 89,636 applications for refugee status in Tapachula and 7,153 in Tabasco, but only 19,273 applications were granted, while 20,364 were granted in Chiapas and 1,499 in Tabasco[19].

Most of the migrants remain in a hopeless limbo, to which they react with stone throwing, fires and clashes with the police[20]. The difference this time is made by Victor Luis García Villagrán, director of the Center for Human Dignification, and Irineo Mújica, director of Pueblos sin Fronteras: they are the ones who organised the march, with the aim of making the voice of the desperate people heard in the Summit rooms, where an absolutely inadequate agreement will be produced[21].

Migrants break through a National Guard line trying to prevent them from leaving Tapachula[22]

The agreement ‘The Los Angeles Declaration’[23] is certainly a step forward and contrasts with the anti-immigration policies of the past Trump administration. Among the main points, Mexico pledges to launch a temporary employment programme for 15,000-20,000 workers from Guatemala, with the intention of also including workers fleeing Honduras and El Salvador; the Biden administration plans to allocate 314 million dollars in humanitarian aid and provide a billion-dollar sum to development banks to support the reception of migrants and refugees in Ecuador and Costa Rica[24]; visas for seasonal non-agricultural workers will also be provided to 11. 500 citizens of Central and North America and Haiti; in addition, Biden promises more efforts to combat human trafficking and pledges to resume family reunification plans with Cuba and Haiti; there will also be joint efforts to try to stem the flight to the US by promoting local job opportunities; and Costa Rica will implement a protection programme for migrants from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba[25].

Many experts, however, judge the agreement to be insufficient, as it is non-binding and will do little on its own: it is promises that, if not followed up by specific implementation programmes, risk remaining on paper[26]. Moreover, it was hatched at a summit where the top leaders of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, Cuba and Venezuela, nations that collectively account for most of the emigration on the US-Mexico border, did not even attend[27].

One result, however, seems to have been achieved: as soon as the Summit ended, the Mexican immigration authorities intervened with the group of 14,000 marching migrants, redirecting them to the Mexican National Migration Institute (INM) and issuing them with visas[28]: a positive truce, even if the problem remains enormous. So far, only vague promises have arrived, while concrete and immediate answers are needed: for these people the choice is often between life and death, as for the Salvadorans fleeing a country torn apart by crime and who are the emblem of the desperate search for salvation.

Between wars, dictatorships, criminal gangs and denied rights

14 July 1969: the ‘football war’ breaks out between El Salvador and Honduras[29]

El Salvador is the smallest and most densely populated non-island state in Latin America, squeezed between Guatemala, Honduras and the Pacific Ocean. It has about 6.5 million inhabitants, more than 85% of whom are mestizo and 12% white, with the remainder divided mainly between indigenous people, Arabs and Armenians[30]. It is home to the continent’s third largest Palestinian community[31], which includes the current President Nayib Bukele, in office since 1 June 2019. More than 3 million Salvadorans reside abroad and of these more than 90% in the United States[32].

Descended from the ancient Maya, the Salvadorans were colonised by the Spanish in 1524, achieved independence in 1821 and became part of the Federation of Central America[33]. In 1841, after the dissolution of the Federation, the Republic was proclaimed. The production and export of coffee became the main economic sustenance, although a powerful oligarchy, called “of the 14 families”, emerged around the activity, which had not only the economy but also politics in its hands[34].

The first free elections in 1931 led to a military coup and the dictatorship of General Maxímiliano Hernández Martínez[35]. In 1950, after a period of internal unrest, during which several military men succeeded each other at the top of power, Oscar Osorío was elected president, who prepared a new constitution and joined the Organisation of Central American States created in 1951[36]. His is a government that, thanks to the favourable economic climate and a low-wage regime, favours the development of infrastructure and a good degree of industrialisation. But the repressive climate and subservience to the Americans (which produced the death squads, right-wing terrorist groups financed by Washington to oppose the communists, responsible for unspeakable disasters[37]) are still a reality today: in 1960 a coup d’état staged by left-wing military deposed President José María Lemus, but the music did not change[38].

Poverty spreads, and in 1960 El Salvador, along with Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua – joined two years later also by Costa Rica – establish the Mercado Común Centroamericano (MCCA), which decrees the beginning of a process of integration that favours the exit from chronic agricultural backwardness[39]. Meanwhile, after the holding of free elections in 1961 was prevented by a new military coup, a new constitution was passed in 1962 to give the country more democracy, but the levers of power still remained in the hands of the military and the ruling oligarchy[40].

The population increases and land is scarce. Thus, in 1967, an immigration treaty was signed with Honduras, which made its uncultivated land available to the Salvadorans: within two years, 300,000 peasants had already crossed the border, most of whom occupied and cultivated plots of land illegally, causing many illegal businesses to proliferate and generating great economic disparity with the residents[41]. This fuels frictions, which are ridden by the nationalist government of Oswaldo López Arellano[42], who came to power through a coup d’état. He cancelled the agreements signed two years earlier, stipulating that land use must be restricted to the country’s natives, and implemented a rapid and violent programme of deportations of immigrants to El Salvador[43].

Diplomatic relations between the two countries, although allied against communism, broke down, tensions exploded and, on 14 July 1969, Salvadoran troops crossed the border, igniting a conflict that lasted only 100 hours, but left 6000 dead, 15,000 wounded and between 60,000 and 130,000 Salvadoran forced repatriations on the ground[44]. The conflict is called the ‘Football War’ because it takes place in conjunction with the 1970 World Cup qualifiers, but football has very little to do with it, except that it is exploited as propaganda to exacerbate the conflict between Honduras and El Salvador[45]. The consequences on a political level are devastating: diplomatic and trade relations remain suspended for years, the MCCA is also suspended, undermining regional integration, and the whole of Central America once again finds itself in the hands of the agrarian oligarchy[46].

The Salvadoran civil war

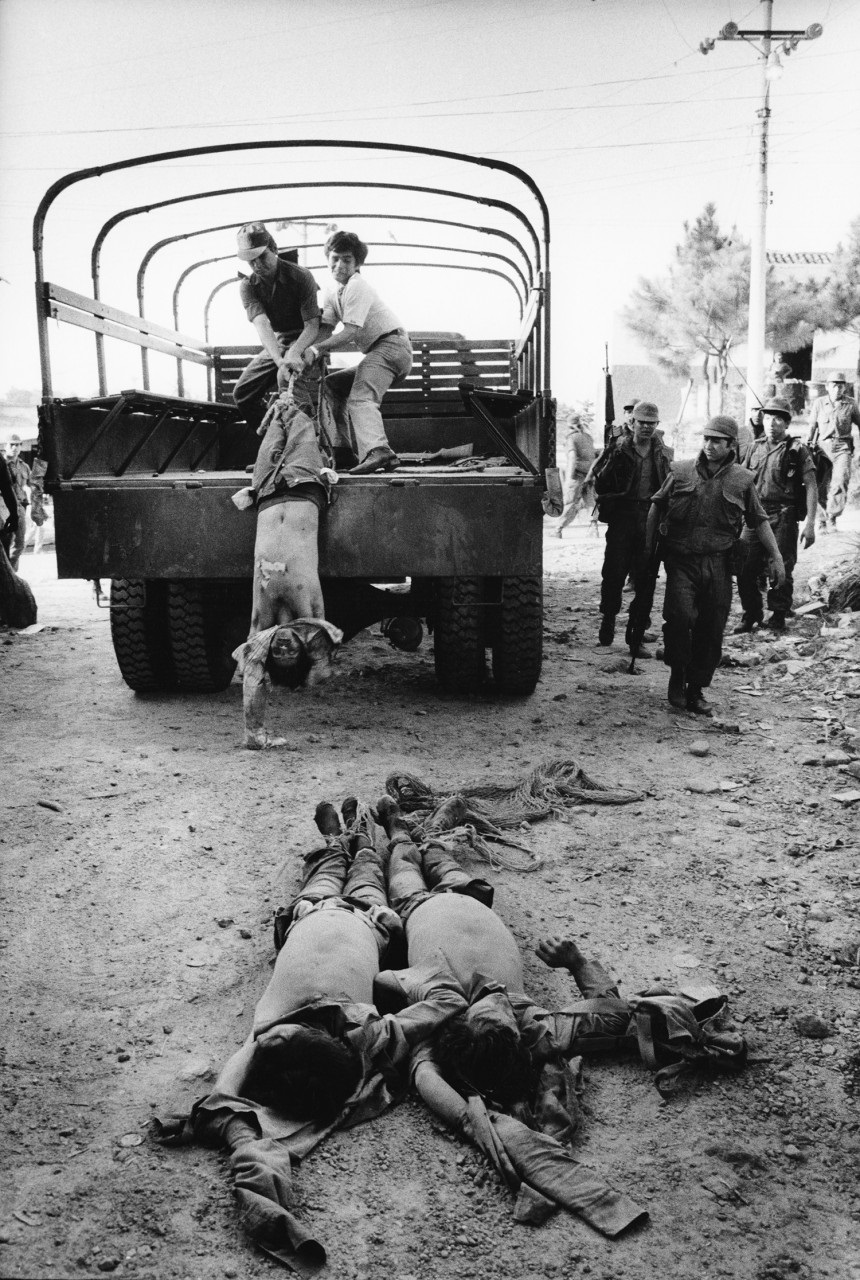

Cuiscatancingo, San Salvador, March 1982: Soldiers load the bodies of slain guerrillas onto a truck[47]

Starting in 1974, in a climate of increasing violence, communist-inspired armed formations carry out numerous kidnappings and political assassinations, and the government responds with force. In 1977, the election of General Carlos Humberto Romero caused serious unrest[48]. Romero was replaced in 1979 by a more moderate junta, composed of military and civilians, but failed in the work of pacification[49]. In March 1977, a commando, possibly armed by the CIA[50], kills the Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, who had sided against the junta[51]: the civil war begins.

A vast alliance, the Revolutionary Democratic Front (FDR), brings together trade unions, workers and peasants, left-wing parties and also part of the Christian Democrats, united in the fight against the regime[52]. In December, the Christian Democrat leader José Napoleón Duarte was elected president, with the blessing of the new US president, Ronald Reagan[53]; from him he obtained aid and military advisers, while the guerrillas enjoyed the support of the Soviet Union, Cuba and Nicaragua[54].

In 1981, the attempt by the Socialist International and the Latin American and European Christian Democratic parties to end the civil war failed. No subsequent government succeeded in finding a way to peace. What changed things was the coming to power of Gorbachev in the Soviet Union and the abandonment of the policy of expansion in Latin America. In 1989, an agreement was reached to dismantle the Contras guerrilla bases in Nicaragua[55]. On 12 December the presidents of the Central American states meeting at the San Isidro summit signed a document calling on the leaders of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the military wing of the FDN, to lay down their arms[56]. In 1990, negotiations took place in Geneva and Mexico between representatives of the government and the FMLN[57].

The parliamentary and local elections of 1991 saw, for the first time in ten years, the non-communist left unite in the Democratic Convergence list, and the country finally moved towards normalisation. In December 1992, with the peace agreement between the government and the FMLN[58], the civil war, which had cost the lives of some 70,000 people, as well as destruction and mass exoduses of incalculable proportions, came to an end.

The USA and crime in Central America: what responsibility?

A cell overcrowded by criminal gang members in the penal centre of Quezaltepeque (El Salvador)[59]

The civil war exodus drives hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans across the US border. Many take refuge in the slums of Los Angeles. Most of them have lost everything, and finding themselves in extreme poverty in a foreign country drives them to seek protection in local gangs, and then to join their criminal activities. The effect on Californian society is dramatic, so much so that, in 1996, the US Congress passed a law allowing the authorities to deport criminals subject to a prison sentence of only one year, an act previously reserved only for criminals convicted of violent crimes and sentenced to five years or more[60].

The law triggers the deportation of tens of thousands of gang members to Central America (at least 20,000), most of whom end up in El Salvador[61]; once they arrive in a land where the situation is already precarious due to severe poverty and chronic lack of opportunities, they can only implement what they have learnt in Los Angeles, moreover enlisting new recruits: the civil conflict has destabilised the local police, who no longer have any control over crime, and in the region overflowing with weapons, they shoot without any qualms.

The main gang in El Salvador has the name Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13 gang, and was formed in Los Angeles, in the neighbourhoods controlled by the Mexican mafia, between the 1970s and 1980s, then exported thanks to the 1996 law. It is the most violent, but it is certainly not the only one: the terrain is fertile and criminal gangs proliferate and wage war against each other, like the eternal war between Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 (another gang originally from Los Angeles), which makes El Salvador the most dangerous place with the highest crime rate in the world: the Ministry of Defence estimates that 500,000 Salvadorans, 8% of the population, are involved in gangs[62]; 2015 is a record year with 103 homicides per 100,000 residents: the highest rate in the world, followed by Venezuela and Honduras[63].

In 2012, then-President Mauricio Funes initiated a negotiation with the Salvatrucha and Barrio18 maras, promising them, in exchange for a truce, less repression, better conditions in prison and investment in rehabilitation programmes for ex-prisoners[64]. In the immediate term, the strategy is successful, murders decrease substantially, but the agreement has devastating consequences: the criminals now have the power to influence politics[65]. The truce lasts the space of a year and in 2013 murder rates reach alarming levels – a gang strategy to bend politics. This time, however, the response is different: in 2016, the legislature outlaws state negotiations with the gangs[66], and arrests 21 officials who made the deals: among the alleged offences are unlawful association, trafficking in illegal goods in prisons, abuse of office, falsification of documents and misappropriation of state funds to the tune of at least $2 million[67].

The so-called ‘death triangle’, where the concentration of crime is the highest in the world[68]

Under Nayib Bukele, president since June 2019, the murder rate drops dramatically from 36 to 18 per 100,000 inhabitants. The reasons lie in his anti-crime programme: modernisation of the security forces, their expansion across the territory and penetration of criminal strongholds, a plan that is tainted by mass detentions without due process[69]. In fact, in August 2021, evidence surfaced that Bukele had implemented a negotiation plan very similar to that of 2012[70].

El Salvador, in terms of criminality, is in good company: Guatemala[71], Honduras[72] and Belize are among the countries with the highest murder and crime rates[73], included in an area called the ‘northern triangle’, also known as the ‘triangle of death’[74]. The common denominator: the presence of gangs, now internationalised, such as the M13, which over the years has become a commercial power with investments in numerous activities, both legal and illegal, and which governs practically every aspect of daily life in the areas where it is present[75].

Honduras is one of the poorest countries in Central America, torn apart by coups, armed revolts, conflicts with its neighbours and hurricanes[76]. Here, the M13 has its main leader Yulán Adonay Archaga Carias, known by the nickname ‘El Porky’. He has a price on his head of USD 100,000 and is wanted by the FBI[77]: in addition to the drug market – he produces synthetic drugs that he resells to various Colombian cartels[78] – he controls numerous activities such as the San Pedro Sula landfill, from which he recovers and recycles tons of materials, and extorts money from a myriad of small businesses and residents, counting on the complicity of local administrations[79]. M13, along with other gangs such as Barrio18, also reigns in Guatemala and Jorge Yahír, alias Célbin, then Vago, finally Diabólico, is its current leader. He is now in prison along with 400 of his cronies. The gang is dedicated to extortion and drug trafficking, but runs many legal businesses such as motorbike taxi companies and car sales[80]. Homicides are also on the rise in this land[81].

USA and Mexico: a hot border

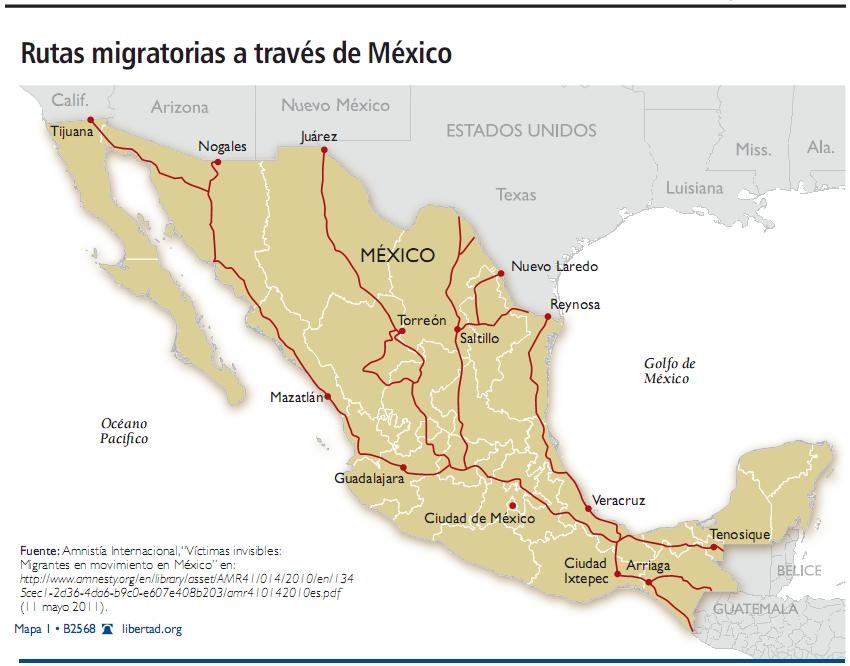

The main routes followed by migrants from the southern to the northern border of Mexico. On the way, the risk of encountering kidnapping, rape, depredation and death is high[82]

The triangle of death borders Mexico: in the imagination of migrants, the road to salvation. A fallacious hope, because here too there is a lack of migratory policies, which strike at the reasons that drive millions of desperate people to leave – and, moreover, if they do arrive in America, they have to deal with the same brutal gangs that had oppressed them at home, since the US government fails to fight them.

The dramatic social crisis in Central America is the product of foreign interventionism, in particular of the USA, which for decades sabotaged the democratic evolution of these countries: the support of criminal gangs was produced by them, to prevent the emancipation of the population. By the time the Cold War ended in 1989, it was too late to realise that they had armed militias that would never again lay down their arms and abandon empires built on drug trafficking.

Over the years, the gangs have created parastatal systems within their respective territories, taking the place of administrations in directing traffic, financing hospitals, all paid for by drug trafficking: it is estimated that there are over fifty gangs within El Salvador, for example. Prisons, horribly overcrowded, are no solution: prison guards merely prevent escapes, but cannot control the inmates. They are afraid of them, so they are free to organise their trafficking as if the prison were a headquarters and recruitment centre[83].

Interventions on the ground are limited to brutal military actions, which only result in bloodbaths. Prevention, here, is an unknown concept. The US, after the Cold War, has limited itself to considering the migration issue on the basis of employment needs, leaving it to the Central American countries to solve the problem. The only major operations adopted by the Pentagon, which often turned out to be counterproductive, were to create special army corps, supported by intelligence, to target individual drug trafficking leaders.

Hillary Clinton, when she was Secretary of State, was the most active in the fight against drug trafficking, allocating several billion dollars to countries and their local police, but the results were disastrous[84]. Obama was the creator of one of the most innovative projects, the CARSI (Central America Regional Security Initiative) through which the police are supported: it is a pity that only half of the funds were used for the agreed cause, the rest was used to strengthen local potentates[85].

12 January 2021: President Trump in Alamo, Texas, inaugurates a section of the wall protecting the border with Mexico[86]

Then Trump arrives, and things get worse: he comes up with the idea of the 6 to 10 metre high and 2000 km long iron wall on the border with Mexico – a useless work, blocked by the Biden administration, costing the dizzying sum of $15 billion (amounts that have risen enormously in the course of construction[87]): it is now a pile of rusty steel piles that run mostly along the Arizona border and often collapse due to corrosion and landslides[88]. What remains are deserted construction sites, beautiful natural areas scarred by dynamite, and piles of materials piled up and abandoned along the border, worth at least USD 350 million[89]. Instead, contracts with construction companies remain standing: according to a report by the Subcommittee on Government Operations and Border Management, the Biden administration at the end of 2021 was still paying up to $3 million a day to subcontractors to guard the wall, construction sites and piled-up materials[90].

Trump does not just put up a wall: the decision is accompanied by measures that undermine human rights, including the extended use of detention even for women and children, increased limits on access to asylum, strengthened enforcement along the US-Mexico border, and lowered thresholds for deportation (even a traffic violation becomes grounds for deportation)[91]. The construction of detention facilities along the southern border, an increase of 10,000 ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) agents, already responsible in the past for violent raids against immigrants, is ordered[92]. Dulcis in fundo, comes the suspension of visas to citizens from Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia and Yemen: their origin is already enough to consider them terrorists[93].

The barrier proves, where completed, to be a sieve – and a dangerous one, because of falls in the attempt to climb over it. The Biden administration, however, does not erase all the past. Apart from halting the construction of the wall, there are only timid signs, such as the amendment to Title 42 allowing humanitarian exemptions to the deportation of unaccompanied minors and families with young children; we have to wait until May 2021 for the number of asylum permits to be raised from the 15,000 envisaged by the Trump administration to the current 125,000[94].

The immigration bill promised by Biden is stalled, thanks in part to the complicated as well as unfavourable political situation for him, with record immigration levels and Republicans who do not fail to ride on popular discontent. But the Los Angeles Declaration, however timid and unpredictable in its implementation, is at least a first clear political signal. But there is no time to lose: northern Mexico is in danger of exploding, it is only a matter of time.

[1] https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/06/biden-summit-of-the-americas-latin-america/661257/

[2] https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/topnews/2022/06/06/per-biden-dittatori-non-vanno-invitati-a-summit-americhe_e1ac5894-779f-4e32-9f8d-ce96f3a93819.html

[3] https://www.voanews.com/a/us-announces-new-plans-on-maritime-cooperation-with-asean-eyeing-china-/6570248.html

[4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/6/mexico-will-skip-us-hosted-summit-of-the-americas

[5] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/venezuelan-president-praises-mexico-for-snubbing-americas-summit/2607451

[6] https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/exclusion-countries-americas-summit-mistake-says-chilean-president-2022-06-06/

[7] https://www.ft.com/content/afd67e97-485c-4ac3-881b-73e8fce07bf1

[8] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/vp-harris-attends-inauguration-honduras-first-female-president-rcna13832

[9] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/19/us-accuses-cuba-of-using-upcoming-summit-as-propaganda

[10] https://www.usnews.com/news/us/articles/2022-06-09/salvadoran-leader-rebuffs-blinken-effort-to-bolster-summit

[11] https://news.gallup.com/poll/394028/biden-job-approval-not-budging-satisfaction-dips.aspx

[12] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-61685118

[13] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-61685118

[14] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jun/03/migrant-caravan-tapachula-mexico-biden

[15] https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF11151.pdf “Central American Migration: Root Causes and U.S. Policy” – Congressional Research Service (CRS) – March 31, 2022

[16] https://www.unhcr.org/5630f24c6.html

[17] https://reliefweb.int/report/mexico/flow-monitoring-migrants-tapachula-and-tenosique-round-1-march-2022

[18] file:///D:/Users/Momo/Downloads/MSF_Forced-to-flee-Central-America_s-Northern-Triangle.pdf

[19] https://reliefweb.int/report/mexico/flow-monitoring-migrants-tapachula-and-tenosique-round-1-march-2022

[20] https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/migrants-clash-with-police-southern-mexico-2022-02-23/

[21] https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2021/10/23/politica/salen-mas-2-mil-migrantes-en-caravana-de-tapachula-a-la-cdmx/

[22] https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/migrants-march-south-mexico-us-weighs-lifting-ban-83813637

[23] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/10/fact-sheet-the-los-angeles-declaration-on-migration-and-protection-u-s-government-and-foreign-partner-deliverables/

[24] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/10/fact-sheet-the-los-angeles-declaration-on-migration-and-protection-u-s-government-and-foreign-partner-deliverables/

[25] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/10/fact-sheet-the-los-angeles-declaration-on-migration-and-protection-u-s-government-and-foreign-partner-deliverables/

[26] https://time.com/6186209/declaration-migration-americas-summit/

[27] https://time.com/6186209/declaration-migration-americas-summit/

[28] https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2022-06-11/mexico-disbands-migrant-caravan-that-set-out-for-u-s-during-americas-summit

[29] https://www.diez.hn/laseleccion/la-guerra-del-futbol-entre-honduras-y-el-salvador-que-nunca-se-ITDZ859230

[30] https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/el-salvador-population

[31] https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/hlps.2020.0230

[32] https://investelsalvador.com/salvadorans-abroad/

[33] https://www.teachingcentralamerica.org/history-of-el-salvador

[34] https://www.centralamerica.com/el-salvador/history/

[35] https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/h/hernandez_martinez.htm

[36] https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/o/osorio_oscar.htm

[37] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230108141_4

[38] https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/lemus-jose-maria-1911-1993

[39] https://www.comex.go.cr/tratados/centroam%C3%A9rica/

[40] https://uca.edu/politicalscience/dadm-project/western-hemisphere-region/el-salvador-1927-present/

[41] https://www.jstor.org/stable/27868774 “Honduras – El Salvador, The War Of One Hundred Hours: A Case OF Regional Disintegration” – Alain Rouquié and Michel Vale – 1973

[42] https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/oswaldo-lopez-arellano

[43] http://countrystudies.us/honduras/22.htm

[44] https://sites.google.com/view/spistoriapoliticainformazione/latinoamericana/la-guerra-del-calcio

[45] https://www.si.com/soccer/2019/06/03/football-war-honduras-el-salvador

[46] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-48673853

[47] https://www.mikegoldwater.com/assignments/editorial-el-salvador-civil-war/

[48] https://www.nytimes.com/1977/03/20/archives/salvadoran-vote-unrest-raises-fear-of-polarization.html

[49] http://countrystudies.us/el-salvador/13.htm

[50] https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2000/mar/23/features11.g21

[51] https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2000/mar/23/features11.g21

[52] https://freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC51_scans/51.elsalvador.fdr.pamphlet.pdf.pdf

[53] https://biography.yourdictionary.com/jose-napoleon-duarte

[54] https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1984/05/13/reports-of-us-covert-aid-seen-hurting-duarte/4f4691f9-260d-4df7-a071-dcd84600ff70/

[55] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-19-mn-2225-story.html

[56] https://delphipages.live/it/politica-diritto-e-governo/politica-e-sistemi-politici/farabundo-marti-national-liberation-front

[57] https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/pwks38.pdf “El Salvador – Implementation of the Peace Accords” – Margarita S. Studemeister -UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE – 2001

[58] https://peaceaccords.nd.edu/accord/chapultepec-peace-agreement

[59] https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/30/el-salvador-gang-violence-ms13-nation-held-hostage-photography/

[60] https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/illegal_immigration_reform_and_immigration_responsibility_act

[61] https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/08/31/long-journey-us-border

[62] https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/30/el-salvador-gang-violence-ms13-nation-held-hostage-photography/

[63] https://insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-homicide-round-up-2015-latin-america-caribbean/

[64] https://elfaro.net/es/201203/noticias/7985/Gobierno-negoci%C3%B3-con-pandillas-reducci%C3%B3n-de-homicidios.htm

[65] https://www.lawfareblog.com/whats-behind-spike-violence-el-salvador

[66] https://insightcrime.org/news/brief/el-salvador-reforms-classify-gangs-terrorists-criminalize-negotiations/

[67] https://es.insightcrime.org/noticias/noticias-del-dia/el-salvador-arresta-funcionarios-durante-intensa-investigacion-tregua-pandillas/

[68] https://www.worldvision.ca/stories/child-protection/northern-triangle

[69] https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/why-has-gang-violence-spiked-el-salvador-bukele

[70] https://insightcrime.org/news/evidence-of-gang-negotiations-belie-el-salvador-presidents-claims/

[71] https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/25-of-politicians-are-linked-to-crime-in-guatemala-city/

[72] https://ticotimes.net/2022/01/28/honduras-poor-violent-and-corrupt-2

[73] https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/BLZ/belize/crime-rate-statistics

[74] https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/events/event/?eventid=85124

[75] https://insightcrime.org/investigations/ms13-and-company/

[76] https://ticotimes.net/2022/01/28/honduras-poor-violent-and-corrupt-2

[77] https://www.elheraldo.hn/honduras/fbi-recompensa-informacion-captura-porky-hondureno-mara-salvatrucha-KYEH1500831

[78] https://insightcrime.org/news/honduras-how-ms13-became-lords-trash-dump/

[79] https://insightcrime.org/news/honduras-how-ms13-became-lords-trash-dump/

[80] https://insightcrime.org/investigations/when-the-ms13-played-possum-guatemala/

[81] https://www.infobae.com/en/2022/03/15/guatemala-has-seen-a-13-increase-in-homicides-in-2022-4/#:~:text=Guatemala%20has%20seen%20a%2013,%2D%20Infobae

[82] https://mexicopasomigrante.wordpress.com/2015/06/01/rutas-medios-de-transporte-y-sitios-peligrosos-de-el-migrante-por-mexico/

[83] https://www.tpi.it/esteri/prigione-el-salvador-senza-guardie-2016031515882/

[84] https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/a-voters-guide-to-hillary-clintons-policies-in-latin-america/

[85] https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/examining-the-central-america-regional-security-initiative-carsi

[86] https://eu.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2021/01/14/trumps-border-wall-plan-has-been-nothing-but-waste-deception-column/4145176001/

[87] https://eu.azcentral.com/story/opinion/op-ed/elviadiaz/2022/03/04/trump-border-wall-mexico-breached-security-joke/9372239002/ ; https://www.propublica.org/article/records-show-trumps-border-wall-is-costing-taxpayers-billions-more-than-initial-contracts?token=3p3X0N3JfobGr1KqFitlqTfpfy7f_krE

[88] https://www.businessinsider.com/pictures-trumps-half-built-border-wall-and-ruined-landscape-2021-2?r=US&IR=T

[89] https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/12/steel-trump-border-wall-rusting-desert/621005/

[90] https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/12/steel-trump-border-wall-rusting-desert/621005/

[91] https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/

[92] https://www.ice.gov/doclib/news/guidelines-civilimmigrationlaw.pdf

[93] https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/

[94] https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/

Leave a Reply