Taiwan is a nation in the balance. Much more so than the state of Israel ever was. Since the international agreement for its independence (1948) [1], the island of Formosa has always looked fearfully across the channel, dreading the day when Chinese armies would annihilate Taiwanese democracy. Great military, commercial and diplomatic pressure from the United States, Japan and the European Union have so far managed to prevent this day from coming – but this is no guarantee for the future, not least because Chinese pretensions have never changed, and lately the threats have become more worrying.

The Taipei government’s strategy is logical: to carefully cultivate its international alliances, to get the other countries of Indochina to also consider the independence of the island of Formosa as a fact of life and a fact of stability for the entire region, as well as an important trading partner. In this sense, Taiwan has managed to make itself indispensable, as it produces the bulk of the world’s semiconductors – the electronic components that are crucial to the scientific, industrial and commercial development of everything to do with digitalisation.

In recent years, however, Taipei has discovered that it has overstepped its bounds: the island’s large industrial complexes require quantities of electricity that are increasing at a dizzying rate from year to year. The island has no significant natural resources and burdens its foreign trade balance (thus decreasing its independence) to buy energy. An intolerable and dangerous situation.

The energy node

7 August 2022: Chinese jet exercise in the skies over Taiwan[2]

Taiwan’s struggle to survive may lead one to believe that the biggest threat Taiwan faces is China and its threats of invasion: the truth is that in order to maintain economic, industrial and military independence, Taiwan needs a huge amount of electricity[3]. This is a sword of Damocles over the heads of the inhabitants of Formosa, and until this problem is solved, everything will remain in the hands of the United States and its fleet – a defence that for us in the West is only necessary as long as the island continues to be a major supplier to our electronics market[4]. Taiwan produces about 65% of the world’s semiconductors and almost 90% of the most advanced chips, making the world dependent on its supplies for iPhones and advanced defence systems[5].

The Chinese land and air military exercises this summer[6], which took place over vast expanses of ocean around Taiwan and began immediately after US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei, were a warning of no small magnitude to the West about China’s new regional policy course. The increased intensity and scale of Chinese incursions has amply justified growing fears that a high level of military pressure will become the ‘new normal’, creating instability and threatening Taiwan’s sea and air trade[7].

Even if a blockade of Taiwan is considered unlikely, it remains on record that Beijing’s crossing of the median line separating the island from China is nevertheless a change in the status quo in the Taiwan Strait[8]. The constant Chinese threat plays a decisive role in the health of Taiwan: 22nd largest economy in the world and 15th largest exporter, with 38% of its turnover accounted for by exports of semiconductors – produced by the giant TSMC Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing & Co. (which produces 92% of the world’s most advanced chips[9]) and other smaller companies (which, incidentally, contributed to GDP growth of 3.3% in 2020 and 6.5% in 2021 – despite the pandemic), Taiwan is vulnerable in terms of energy as it is totally dependent on foreign supplies[10].

In 2016, domestic energy production covered only 2% of Taiwan’s total consumption. 98% is imported and comes mainly from fossil fuels, with 48% derived from coal, 29% from oil and only 13% from natural gas[11]. At that time, the Taipei government began a huge effort to change this, but with limited success: in 2018, foreign oil produced 48.28% of energy, followed by coal (29.38%), natural gas (15.18%), nuclear power (5.38%), biomass and waste (1.13%) and with a laughable share of green energy (0.64%)[12].

Although the number of inhabitants decreases, and the government invests money to increase the share of self-generated energy[13], industrial and civil demand for electricity grows inexorably[14]. In 2020, total electricity consumption reached 271 billion kWh, an increase of 5.5 billion kWh over the previous year[15]: a figure that amply illustrates the severity of the problem[16].

Historical trend of annual electricity production in Taiwan[17]

The natural gas deposits discovered in Guantian (2004) and Gongguan (2012), estimated at one billion cubic metres[18], are not enough[19] and force Taiwan into a dangerous dependence on supplies from Qatar, Australia, the United States and Russia[20]. Gongguan has been the oil-supplying area of the national oil company CPC since the 19th century[21]. In 2012, Taiwan produced an average of 20,000 barrels per day and planned to explore off the island of Taiping[22]. The reserves stored in the depots are infinitesimal[23] and would not be enough to sustain supply for a year[24], so the island is easily blackmailed[25]: ‘While Taiwan’s oil stocks would be sufficient for 138 days, the island would be less resilient with regard to electricity’ as ‘importers of natural gas are currently required to hold only an eight-day supply, which makes them vulnerable to any potential Chinese action’[26].

This is despite the fact that CPC has undertaken very costly potential assessment activities in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea – two areas disputed between China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines and Taiwan[27] – and are therefore not suitable to solve the problem[28]. According to an analysis of data from Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs[29], ‘stockpiles slightly exceed minimum requirements with 39 days of coal, 146 days of oil and 11 days of natural gas’ – should ‘China implement a total or even partial blockade, Taiwan would suffer severe damage to its economy after 11 days as natural gas accounts for about 37% of electricity production and oil-fuelled production is negligible’[30].

The other Asian countries are well aware of this. On 27 October 2022, at the ASEAN meeting on the humanitarian crisis in Myanmar[31] (a bloodthirsty regime[32] that Beijing is using in an anti-Indian vein, given the great industrial and economic growth of this country[33]), the members of the League of Far Eastern Countries expressed enormous concern about China’s attitude towards Taiwan, because they fear a naval blockade that would wipe out the supply of semiconductors, on which these growing economies are totally dependent[34].

The role of ASEAN

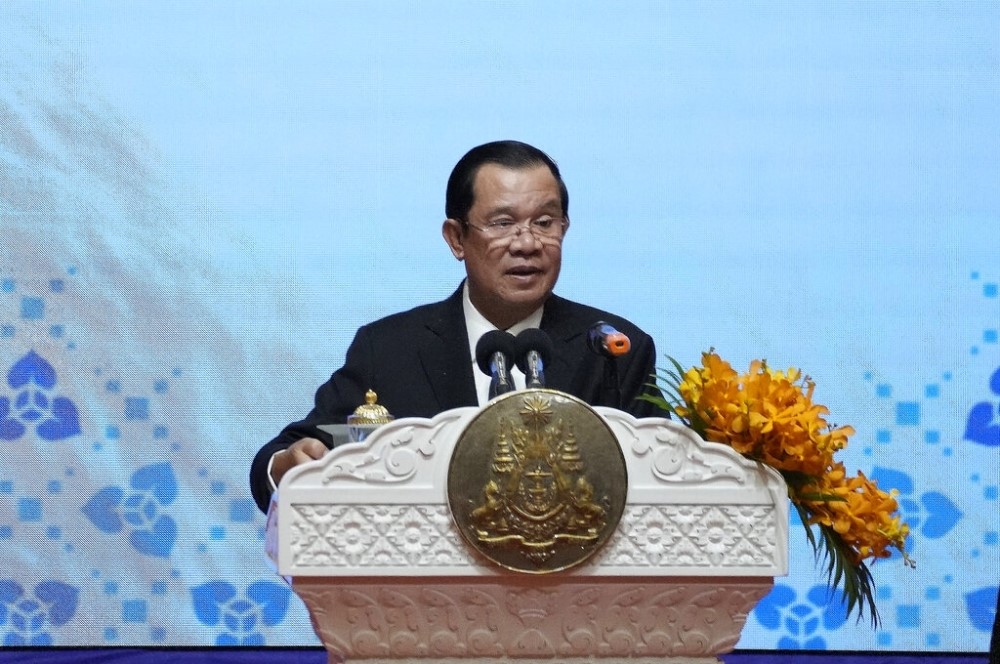

3 August 2022: Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, speaking at the ASEAN conference, warns of the very serious risks of a possible military isolation of Taiwan for the entire Far East[35]

Cambodia currently holds the rotating chairmanship of ASEAN, and Prime Minister Hun Sen showed great courage by inviting Ukrainian President Zelensky and US President Joe Biden[36]. The meeting follows a bilateral meeting between ASEAN and the United States (12-13 May 2022) at which Cambodia had managed to convince the other member states to decisively condemn the Burmese regime, Russia’s invasion and the Far East’s choice of camp in favour of the United States and thus against China: a development unthinkable only a few years ago[37].

In 2016, the newly elected (in the ranks of the DPP, the strongly independentist Democratic Progressive Party[38]) President Tsai Ing-Wen launched the New Southbound Policy, with the aim of ‘realigning Taiwan’s role in Asian development, seeking new directions and momentum for the country’s new phase of economic development’ through alliances within ASEAN and with India, Australia and New Zealand – with the hope of stepping out of China’s political, military and commercial shadow[39]. The retaliation was not long in coming: a drop in Chinese tourist arrivals, countered by the abolition of visas for tourists from Indo-China countries[40], which brought a tourist surplus of USD 3.45 billion, thanks to which an infrastructure development plan was financed[41].

The multiplication of lucrative Chinese projects throughout South-East Asia and the dependence of the region’s economy on Beijing’s investments have meant that ASEAN countries have long been reluctant to develop deeper relations with Taiwan – good relations that are not very welcome in China, as evidenced by China’s ‘exhortation’ to abide by its One China Policy[42]. A strategy that bought time, gained Chinese funding, but never broke the link with Taipei[43]. An almost obligatory choice in the years of the Trump presidency, which has always rejected dialogue with Indochina[44].

Joe Biden’s entry into the White House was the new fact that, with the coup d’état in Myanmar, changed the cards on the table[45]: the Far East rejects (rightly) the destabilising force of NATO that led to the war in Vietnam[46], but is open and interested in collaboration with the West in the face of the common fear of China[47]. Once Biden demonstrated Washington’s desire to consider Indochina an ally (including economic and trade), ASEAN excluded Myanmar from its meetings, decided to enforce sanctions against Russia, and openly sided with Taiwan[48].

The energy project

Greater Changhua 1 and 2a are Taiwan’s first large-scale offshore wind projects[49]

If China is the world’s largest factory, Taiwan is its technological beating heart, producing around 65% of the world’s semiconductors and over 90% of the most advanced chips, which is why the Taiwanese TSMC factory alone consumes 6% of the country’s electricity today – an amount that will double[50] by 2025 when the new factories are ready[51]. Of gas and oil we have already said: they are not enough. Taiwan has no rivers that can generate hydroelectric power, the overpopulation leaves no room for solar power plants, and the population is against nuclear energy.

The consequences are serious: in recent years, the island has suffered blackouts several times due to the overloading of existing power plants[52]: the increase in consumption means that blackouts become more and more frequent, and old plants are increasingly difficult to repair[53]. For this reason, Taiwan today depends on importing foreign electricity – which needs adequate cables, which are not there. The Taipei government has decided to focus on green energy: increase the use of natural gas, reduce the use of coal and end the use of nuclear energy[54].

In recent years, then, the Taiwanese government has set particularly ambitious targets for renewable energy, with a focus on developing its capacity in the offshore wind energy sector, for which the government is ready to invest impressive sums, thus attracting manufacturers from around the world – Taipei, in fact, wants to increase the currently available electrical power tenfold and wants to do so as soon as possible[55]. In 2021, the Jones Day White Paper was published, reforming the legislative framework: the procurement rules, the environmental approval process, the grid allocation process, the approval/licensing regime for offshore wind developers (e.g. foreign ownership limits, foreign exchange controls, etc.), all with the intention of providing investors with solid certainty[56].

The initial target is to grow by 5.6 GW by 2025 thanks to investments of NT$ 865.6 billion (around USD 28 billion), which will lead to the creation of around 20,000 new jobs, the annual generation of 20 TWh of electricity, and a simultaneous reduction in CO2 emissions of 10.5 million tonnes per year[57]. The plan is divided into three phases: a) the Demonstration Incentive Programme (DIP); b) the Zones of Potential; c) the Zonal Development, each with a separate grid allocation. Initially, the project envisaged the construction of three wind farms named (Formosa 1, Formosa 2 and Formosa 3), to which Formosa 4 was added, to be commissioned in 2025 and consisting of a 4400 MW offshore wind project in the South China Sea[58]. The project was developed by J&V Energy Technology, Swancor Renewable Energy, Tien Li Offshore Wind Technology and Yeong Guan Energy Technology, and is currently owned by Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners[59].

The first park, Taiwan’s 1st Offshore Wind Farm, began commercial operation in April 2017 off the coast of Miaoli County, on the northwestern side of the island, and is led by the Germans of Swancor Renewable (Synera Group)[60]. The initial plant consists of two wind turbines of 4 MW each, installed in November 2016[61]. The second part went online in December 2019, and consists of 20 SWT-6.0-154 turbines from Siemens Gamesa with a total capacity of 120 MW[62], and produced its first electricity at the end of 2021[63].

The three phases of the OWE project (Offshore Wind Energy)[64]

Taiwan’s 2nd Offshore Wind Farm (a 376 MW offshore wind project comprising 47 Siemens 8 MW turbines installed in water depths of up to 55 metres) has completed the installation of twelve turbines as at 21 July 2022 and has started supplying power to the national grid[65]. The wind farm, also located offshore in Miaoli County, is already half ready, and more than a quarter of the planned wind turbines have been installed[66] ‘despite adverse weather conditions’, and ‘with high health, safety and environmental performance and high sustainability standards’[67].

The installation of jacket foundations and subsea inter-array cables did not begin until April 2022, while turbine installation began in early June, and in July, Saipem completed the fabrication of 32 wind turbine jacket foundations. The park is being developed by the Americans of JERA, the Australians of GIG Green Investment Group, and the Germans of Swancor Renewable Energy: once completed, it will provide renewable electricity for the needs of some 380,000 households[68].

It is a cyclopean project, still nearing completion[69]: in August 2022, the last of 188 support pylons was installed, each 78.9 metres long, with an external diameter of 2.4 metres and weighing 280 tonnes[70]. The work was subcontracted several times, due to its difficulty, and was completed by the Italians of Saipem[71] and Singapore’s[72] Sembcorp[73]. On 1 September, the 47 foundations of the wind turbine casing and the submarine cables[74] were installed. On 21 September, the British company EDS HV[75] was awarded a multi-million dollar contract for high voltage grid support services[76].

Everything seems to be proceeding at great speed, but appearances often deceive. On 30 September, in fact, the Danish multinational Ørsted[77] decided to withdraw its bid in the first auction of Round 3 of the development phase: ‘As the largest and most experienced offshore wind developer in Taiwan, we had to take stock of the constraints imposed by current regulations, which in combination with high inflation and rising interest rates led us to conclude, after exhausting all efforts, that we could not make the projects sustainable’[78].

Ørsted is the largest shareholder (35 per cent) of the first commercial-scale offshore wind project, Formosa 1, and its 900 MW Greater Changhua 1 & 2a wind farm will soon come on stream; meanwhile, the company is pressing ahead with the development of its next wind farm, also in Taiwan, the 920 MW Greater Changhua 2b & 4, for which it won the construction rights in Taiwan’s first offshore wind auction in 2018[79]. The reason for abandoning Formosa 3 is summarised in the Global Offshore Wind Report 2022, in which Ørsted also participates: ‘World governments must urgently put in place the policies and regulatory frameworks to deliver on their promises’[80]. which means that economic, industrial and legal promises are not being kept, and that part of Taiwan’s cyclopean project rests on feet of clay.

Offshore Windfarm Projects Review in Taiwan Island 2019[81]

Here’s why: Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs released the plan for Phase 3 on 19 August 2022 for projects scheduled to come on stream between 2026 and 2035[82]. It would already be too late, but the official document says that the decision on whether individual batches will be 1 GW or 1.5 GW is still postponed: a 50% increase[83]. For companies, under these conditions, it is impossible to plan expenditure and the construction of a plant[84]. Add to this the problems of supply delays due to the pandemic, the war in Ukraine[85], and certain national crises – all variables that can turn a wind farm into the grave of a construction company[86].

Applicants can only be admitted to bidding after a ‘performance capability assessment’ and the submission of site approval documents (nine letters of evaluation), preliminary approval of the EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment) and Taipower Grid Feasibility (compatibility with the Taipower power grid) – an old and damaged grid, unsuitable to support the distribution of increased electricity production[87]. Maintaining a stable power supply is one of the most significant challenges facing the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Taipower[88]: the most recent forecasts speak of a growth in energy consumption of 2.5 per cent per year, i.e. something 26.4 per cent higher than the previous estimate[89].

According to the operators, however, even this new estimate is optimistic, given the increase in blackouts[90], so the government document announces the possibility of a new adjustment of the tender with the allocation of licences for the production of another 100MW, which, at this point, no company in the world would be able to realise on time and with the expected costs[91]. This being the case, however, one can understand why a large company like Ørsted is backing out and why others, who have been part of the plan for years, are raising with the government the question of a new distribution of costs and benefits, so that they can amortise the construction and installation costs[92].

The big mistake made by Taipei was to have invested huge financial resources in the development of offshore wind energy, without first rebuilding the power grid and distribution plants, and without worrying about possible price increases due to the government’s erratic regulation[93]. An effective legal and administrative framework was lacking, creating a centralised state agency empowered to make immediate strategic and spending decisions[94]. The grid has not been updated, and the just demands of those already working in the sea have not been taken into account, as the fishing industry contributes 14% to the national GDP and will be deeply damaged by offshore wind farms[95]. More generally, the issue of popular will was ignored[96].

The Chinese threat, the Indochina alliance

Chinese jets and ships around Taiwan. Beijing: ‘Action needed against collusion with the US’[97]

The wind project is a matter of life and death. On 25 August 2022, the ‘Taipei Times’ writes: ‘Wind farm projects stimulate foreign direct investment. These have contributed (43% of the total) to triple in just one year (+ USD 9.69 billion) [98], but Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Formosa was enough to trigger Xi Jinping’s threats and military exercises, which, coupled with the shortcomings of the Taiwanese wind project, immediately caused the foreign investment figure to drop by a third[99]. Approved bids in the first seven months of 2022 dropped 7.04% year-on-year[100].

The curve rose again as soon as Biden and Xi Jinping shook hands on 14 November 2022[101]. The truce in the dispute between the two superpowers gravitating over the Pacific, Taipei knows very well, is not just a positive sign[102]. It means that, more or less secretly, and with Washington’s silent complacency, Chinese industries are taking over the shares of construction licences that Western companies have given up[103]. An intensification of Chinese military exercises along the sea lanes around Taiwan could potentially not only disrupt Taiwan’s exports and delay or interrupt incoming shipments of energy, minerals, foodstuffs and other critical components, but also jeopardise the integrity and success of the Taiwanese wind project[104].

The Chinese threat is responsible for the confusion generated by the need for a reshaping of the Round 3 rules to speed up the construction of planned plants and increase the power output: a necessity that is economically and industrially unacceptable to companies like Ørsted[105]. Taiwan is lagging far behind, because the countries of Indochina (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) have long been engaged in thermal and hydroelectric power projects, the aim of which is to enable economic growth, but also to secure independence from China[106].

Vietnam has an advantage over its neighbours: it has a large financial operator (SAM Saigon Asset Management) committed to managing funds for Indo-Chinese energy implementation[107], and the State’s plan (Master Plan 7) is already well underway and has provided for new investments of USD 48.8 billion, tripling the country’s electricity capacity[108]. As the price set by the government for electricity was too low, the plan slowed down after 2020, but the deregulation of the last two years has restored attractiveness and momentum to Vietnam’s ecological transition[109].

Cambodia is the one with the highest prices, but it does so because it produces electricity almost exclusively with diesel, which nowadays costs insane amounts of money – which is why the government has just launched the tender for 15 new renewable energy projects[110]. As for Laos, its electricity production is the main component of GDP: a cornerstone of the local industrial development policy[111]. Although Laos’ economy is mainly based on agriculture and livestock farming, its economic growth has been among the fastest in Asia thanks to exports of natural resources, including hydropower, for which the country has earned the nickname ‘Southeast Asia’s battery’[112]. In 2018, with a total installed capacity of 519 GW, Indochina is the region on the planet that hosts a third of the world’s entire hydropower production[113].

The Baihetan Power Station (China): the largest hydroelectric project in the world, producing 10 billion kwh of clean electricity per year – a reduction of 8.38 million tonnes of carbon dioxide[114]

Fortunately, not far from Taiwan, there are two economies that are growing at an impressive pace, have excellent diplomatic and trade relations with Taipei, and share the fear of China: India and Indonesia. The latter is the most populous country and the largest economy in South-East Asia, and although 98.1% of the country is now served by electricity, the growing need for energy and electronics makes Taipei the great hope for Indonesia’s economic boom[115].

The primary energy supply in Indonesia is mainly based on fossil fuels: in 2015, 41% of Indonesia’s energy consumption was based on oil, 24% on natural gas and 29% on coal, while renewable energies, in particular hydro and geothermal, account for a 6% share, although the statistics do not take into account the traditional use of biomass, which is estimated to account for between 21% and 29% of total energy demand[116]. Today, only 8.15 per cent of Indonesia’s hydropower potential is exploited, which corresponds to only 7.6 per cent of the national demand[117]. The Djakarta government wants to meet its goal of increasing the market share of renewable energy to 23% by 2025, and the two ways to avoid a deal with Beijing are to exploit the large hydropower potential and to purchase green energy from friendly countries – such as Taiwan[118].

Both Indonesia and other ASEAN countries are strongly motivated to help and support Taiwan’s independence, so as to ensure free trade in semiconductors and to have a solid and reliable ally just a few kilometres from the Chinese coast. Gone is the time when the Far East needed Beijing to sustain its growth, the economies of Indochina have become strong and aggressive – and are the expression (except for Myanmar) of democratic-led and religiously tolerant countries. The European Union is right to include Taiwanese companies in its development programmes in robotics, digital security, healthcare, microelectronics – and, of course, renewable energy[119].

And that is why Taipei’s cyclopean, courageous, perhaps disorganised effort to achieve energy independence and the transition to renewable energy in a single decade must be supported by us Europeans with conviction, consistency, and avoiding falling into the umpteenth trap of being caught between Russian, Chinese, and American interests. Indochina is a key ally, and Taiwan is, in every sense, an island of reason in a quadrant of imperialist militarism.

[1] https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_3.php

[2] https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-military-begins-fresh-taiwan-drills-showing-new-normal/article65746827.ece

[3] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[4] https://www.ispionline.it/it/print/pubblicazione/taiwan-sfida-sullo-stretto-36003

[5] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[6] https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3188257/mainland-china-declares-military-drills-will-continue-around ; https://asiatimes.com/2022/08/chinas-taiwan-strait-drills-the-new-normal/

[7] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[8] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[9] https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/nancy-pelosi-taiwan-visit-china-us-tensions/card/taiwan-s-energy-supply-is-vulnerable-to-china-retaliation-economist-says-PrV8K5k11XrXuKlkvOXt

[10] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[11] https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2020/05/taiwan-energy-independence/

[12] Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs. Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs. 2019-08-01 https://www.moeaboe.gov.tw/ECW/english/content/ContentLink.aspx?menu_id=1540

[13] https://e-info.org.tw/node/229789

[14] https://e-info.org.tw/node/229789

[15] https://e-info.org.tw/node/229789

[16] https://e-info.org.tw/node/229789

[17] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_in_Taiwan

[18] https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-are-the-major-natural-resources-of-taiwan.html

[19] https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/nancy-pelosi-taiwan-visit-china-us-tensions/card/taiwan-s-energy-supply-is-vulnerable-to-china-retaliation-economist-says-PrV8K5k11XrXuKlkvOXt

[20] https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/nancy-pelosi-taiwan-visit-china-us-tensions/card/taiwan-s-energy-supply-is-vulnerable-to-china-retaliation-economist-says-PrV8K5k11XrXuKlkvOXt

[21] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2021/05/28/2003758176 ; https://www.moc.gov.tw/en/information_247_125403.html

[22] https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-are-the-major-natural-resources-of-taiwan.html

[23] https://www.worldometers.info/oil/taiwan-oil/

[24] https://www.worldometers.info/oil/taiwan-oil/

[25] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[26] https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/nancy-pelosi-taiwan-visit-china-us-tensions/card/taiwan-s-energy-supply-is-vulnerable-to-china-retaliation-economist-says-PrV8K5k11XrXuKlkvOXt

[27] https://www.limesonline.com/rubrica/una-bomba-geopolitica-nel-mar-cinese-meridionale-2

[28] https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?post=36813&unit=29,45 ; https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/TWN

[29] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[30] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[31] https://www.glistatigenerali.com/asia_geopolitica/la-stupidita-e-la-ferocia-al-potere-scene-da-un-myanmar-nel-caos/

[32] LA STUPIDITÀ E LA FEROCIA AL POTERE: SCENE DA UN MYANMAR NEL CAOS | IBI World Italia ; GLI INTRIGHI FINANZIARI DIETRO IL SANGUINOSO COLPO DI STATO DEL MYANMAR | IBI World Italia

[33] https://www.glistatigenerali.com/asia_geopolitica/la-stupidita-e-la-ferocia-al-potere-scene-da-un-myanmar-nel-caos/

[34] https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/nancy-pelosi-taiwan-visit-china-us-tensions/card/taiwan-s-energy-supply-is-vulnerable-to-china-retaliation-economist-says-PrV8K5k11XrXuKlkvOXt

[35] https://www.manilatimes.net/2022/08/04/news/world/pelosis-visit-to-taiwan-dominates-asean-meet/1853291

[36] https://apnews.com/article/putin-biden-asia-indonesia-business-1c82e0cb86085b1dcb19a8d9f65e8be0

[37] https://asean2022.mfaic.gov.kh/files/uploads/LTP2CXTA2H5Y/Final-ASEAN-US-Special-Summit-2022-Joint-Vision-Statement.pdf

[38] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-38285354

[39] https://theaseanpost.com/article/taiwans-pivot-southeast-asia

[40] https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/new-southbound-policy-and-india-taiwan-relations.pdf

[41] https://theaseanpost.com/article/taiwans-pivot-southeast-asia

[42] https://theaseanpost.com/article/taiwans-pivot-southeast-asia

[43] https://theaseanpost.com/article/taiwans-pivot-southeast-asia

[44] https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Outlook-on-the-Indo-Pacific_FINAL_22062019.pdf ; The Asian 21st Century” di Kishore Mahbubani, Asia Research Institute

National University of Singapore Singapore, Singapore Cap. ASEAN’s Quiet Resilience, Pag 77 e seguenti https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-981-16-6811-1.pdf#page77

[45] https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-981-16-6811-1.pdf#page77

[46] https://mahbubani.net/asia-say-no-to-nato-the-straits-times/

[47] https://www.corriere.it/oriente-occidente-federico-rampini/22_novembre_12/america-cina-decoupling-5555e288-626b-11ed-b76c-5099773a656c.shtml

[48] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-is-asean-holding-special-meeting-myanmar-2022-10-27/

[49] https://www.theguardian.com/power-of-green/2022/aug/10/taiwan-wind-power-renewable-energy-transition

[50] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-25/energy-efficient-computer-chips-need-lots-of-power-to-make?leadSource=uverify%20wall

[51] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[52] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[53] https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Tech/Semiconductors/TSMC-struggles-to-keep-new-hires-warns-of-power-supply-risks

[54] https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/taiwans-greatest-vulnerability-is-its-energy-supply/

[55] https://www.jonesday.com/-/media/files/publications/2021/08/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-update/files/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-white-paper/fileattachment/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-white-paper.pdf

[56] https://www.jonesday.com/-/media/files/publications/2021/08/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-update/files/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-white-paper/fileattachment/taiwan-offshore-wind-farm-projects-white-paper.pdf

[57] https://www.twtpo.org.tw/eng/intro/

[58] https://www.power-technology.com/marketdata/formosa-4-offshore-wind-project-taiwan/

[59] https://www.power-technology.com/marketdata/formosa-4-offshore-wind-project-taiwan/

[60] https://sreglobal.com/en/about/

[61] https://sreglobal.com/en/about/

[62] https://focustaiwan.tw/business/201708060010

[63] https://www.windtech-international.com/projects-and-contracts/production-start-up-of-the-yunlin-offshore-wind-farm-in-taiwan

[64] https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/sustainability/sustainability-13-10465/article_deploy/sustainability-13-10465-v2.pdf?version=1632410505

[65] https://www.windtech-international.com/projects-and-contracts/production-start-up-of-the-yunlin-offshore-wind-farm-in-taiwan

[66] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/07/21/formosa-2-offshore-wind-farm-hits-major-construction-milestones/

[67] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/07/21/formosa-2-offshore-wind-farm-hits-major-construction-milestones/

[68] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/07/21/formosa-2-offshore-wind-farm-hits-major-construction-milestones/

[69] https://www.offshorewind.biz/?sort=relevancy&s=formosa+2&post_type=

[70] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/08/23/last-pin-pile-in-place-at-formosa-2-offshore-wind-farm/

[71] https://www.saipem.com/en

[72] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/08/23/last-pin-pile-in-place-at-formosa-2-offshore-wind-farm/

[73] https://www.sembcorp.com/en/

[74] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/09/01/all-foundations-subsea-cables-installed-at-formosa-2/

[76] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/09/21/james-fisher-joins-formosa-2-team/

[78] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/09/30/orsted-will-not-bid-in-first-round-3-offshore-wind-auction-in-taiwan/

[79] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/09/30/orsted-will-not-bid-in-first-round-3-offshore-wind-auction-in-taiwan/

[80] https://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GWEC-Offshore-2022_update.pdf

[81] https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/hai-long-offshore-wind-farm/

[82] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2021/08/19/taiwan-finalises-15-gw-offshore-wind-allocation-plan-for-2026-2035/

[83] https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/populace/news/News.aspx?kind=1&menu_id=40&news_id=96475 ; https://www.offshorewind.biz/2021/08/19/taiwan-finalises-15-gw-offshore-wind-allocation-plan-for-2026-2035/

[84] https://renews.biz/79621/orsted-boss-calls-for-offshore-local-content-changes-in-taiwan/

[85] https://www.offshorewind.biz/2021/08/19/taiwan-finalises-15-gw-offshore-wind-allocation-plan-for-2026-2035/

[86] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fM82917GI0bzEO8vfgwWp_2KfIs6mJfX/view ; https://www.offshorewind.biz/2022/08/11/taiwans-largest-offshore-wind-farm-to-come-online-later-than-expected/

[87] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2022/02/08/2003772725 ; https://www.offshorewind.biz/2021/08/19/taiwan-finalises-15-gw-offshore-wind-allocation-plan-for-2026-2035/

[88] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2022/02/08/2003772725

[89] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2022/02/08/2003772725

[90] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2022/02/08/2003772725

[91] https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/populace/news/News.aspx?kind=1&menu_id=40&news_id=96475

[92] https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/sustainability/sustainability-13-10465/article_deploy/sustainability-13-10465-v2.pdf?version=1632410505

[93] https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/sustainability/sustainability-13-10465/article_deploy/sustainability-13-10465.pdf

[94] https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/enepol/v109y2017icp463-472.html

[95] file:///C:/Users/Asus/Downloads/fishes-07-00114-v2.pdf

[96] https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/sustainability/sustainability-13-10465/article_deploy/sustainability-13-10465-v2.pdf?version=1632410505 ; Tech News. A Clear National Project, a Real Quiet Revolution, and an Offshore Wind Turbine. 2020. Available online: https://technews.tw/2020/05/03/changhua-offshore-wind-power-industry-project/ ; Taiwan Environmental Information Association. Offshore Wind Turbines Destroy Fishing Grounds: Yunlin County’s Fishers Call for Stopping Construction of Offshore Wind Turbines. 2020. Available online: https://e-info.org.tw/node/226272

[97]https://www.repubblica.it/esteri/2022/06/01/news/jet_e_navi_cinesi_intorno_a_taiwan_pechino_azione_necessaria_contro_la_collusione_con_gli_usa-352061888/

[98] https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2022/08/25/2003784097

[99] https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3197042/taiwans-foreign-investment-surges-no-short-term-issues-china-clouds-outlook

[100] https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3197042/taiwans-foreign-investment-surges-no-short-term-issues-china-clouds-outlook

[101] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/14/readout-of-president-joe-bidens-meeting-with-president-xi-jinping-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

[102] https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/crossing-the-line-the-makings-of-the-4th-taiwan-strait-crisis/

[103] https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/crossing-the-line-the-makings-of-the-4th-taiwan-strait-crisis/ ; https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/11/21/a-dangerous-game-over-taiwan

[104] https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/crossing-the-line-the-makings-of-the-4th-taiwan-strait-crisis/

[105] https://www.moea.gov.tw/MNS/english/news/News.aspx?kind=6&menu_id=176&news_id=98736 ; https://www.infrastructureinvestor.com/taiwan-offshore-debacle/ ; https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[106] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[107] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[108] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[109] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[110] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects

[111] https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects ; https://www.andritz.com/resource/blob/342550/932bfd1e57f5d11c0557cb923660b45d/15-lao-data.pdf

[112] https://www.andritz.com/resource/blob/342550/932bfd1e57f5d11c0557cb923660b45d/15-lao-data.pdf ; https://asian-power.com/project/in-focus/indochina-amp-investments-in-thermal-and-hydro-power-projects ; https://www.andritz.com/hydro-en/hydronews/hydro-news-asia/laos

[113] https://www.andritz.com/hydro-en/hydronews/hydro-news-asia

[114] https://italian.cri.cn/notizie/cina/3204/20220505/754183.html

[115] https://www.andritz.com/hydro-en/hydronews/hydro-news-asia/indonesia

[116] https://energypedia.info/wiki/Indonesia_Energy_Situation

[117] https://www.andritz.com/hydro-en/hydronews/hydro-news-asia/indonesia

[118] https://www.andritz.com/hydro-en/hydronews/hydro-news-asia/indonesia

[119] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/taiwan/european-union-and-taiwan_en?s=242#2816

Leave a Reply