In June 2022, Tanzanian police officers and authorities beat and shoot at the inhabitants of a Maasai village. They also indiscriminately hit old people and children. Poor people protesting in defence of their land, destined as hunting reserves for rich foreigners[1]. These are dark days: officially, 31 people are seriously injured, a Maasai and a policeman lose their lives[2], but the real numbers, like the truth about what happened, emerge with difficulty, due to the intimidation of journalists, lawyers and civil society organisations by the Tanzanian government[3]. The violence and abuse suffered is nothing new, but one among many episodes that have been going on for a long time[4].

For the Maasai it is like a destiny that cannot be escaped, persecutions thousands of years old that have been recounted from generation to generation[5]. In the 15th century[6] the people, originally from the lower Nile valley, north of Lake Turkana, migrated and occupied a large portion of the strip of land between northern Kenya and central Tanzania, known as the Great Rift Valley[7]. In the 19th century, when the British conquered Tanzania and turned it into a Crown Colony, the Maasai were at their most extensive, occupying the entire country[8]. From 1904 onwards, London forced them to make way for British colonial ranches[9] and the creation of national parks[10], such as the Ngorngoro Conservation Area[11] (UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1959[12]), the Masai Mara National Reserve[13], Samburu[14], Amboseli National Park[15], Nairobi[16], Tarangire[17], Lake Nukuruku[18] and Sergenti[19].

Through violence and forced relocations, the British colonisers led to the reduction of 60%[20] of the land in the 1940s, destroying Maasai homes and herds. The work was continued by the Dar-es-Salaam government even after independence. These are some of the most beautiful areas in the world, with a wonderful variety of flora and fauna, seasonal spectacles such as the great wildebeest and zebra migration, unique in its kind, which secures the Great Rift Valley’s place among the seven wonders of the world[21].

The new Tanzania does not want the Maasai, but it does want their land: the ACHPR (African Commission on Human and People’s Rights[22]), at the conclusion of the African Commission on Human Rights promotion mission (23-28 January 2022), expresses great concern about the violation of fundamental rights, particularly in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area sites in the Arusha region[23]. Lawyer Joseph Moses Oleshangayi, an activist on the side of the Maasai[24], points the finger at the hidden economic interests behind a nature conservation project that actually consists of reserving some of the protected areas for the construction of hotels and exclusive hunting reserves[25].

The definition of these areas began on 7 June 2022, when unspecified ‘military and paramilitary forces’[26]. in the Ngorongoro Area, seize an area of 1500 km2 of the Maasai tribe, without any warning or consent of the population[27]. They erect barriers and set up checkpoints, whereupon tribesmen from the villages of Ololosokwan, Oloirien, Kirtalo and Arash, all located in Loliondo, gather on 9 June 2022 to protest and remove the barbed wire: the Tanzanian police react with 27 arrests, without contact with lawyers, and formally accuse them of murder[28].

2017: Villages set on fire by police forces in Maasai villages in Loliondo, Tanzania[29]

Their lawyer, Paul Kisabo, explains that the arrests are an attempt to intimidate the community, as more than half of them occurred before the murder of police officer Mwita Garlus[30] announced on 11 June 2022 by the commissioner of the region, John Mongella[31]. In the clashes, police forces use rifles and tear gas against the crowd, causing a mass stampede to the state of Kenya: in Tanzania, you cannot receive medical treatment following a gunshot wound without first obtaining police clearance. And if you have been wounded by the police, there is a risk that instead of finding a place in hospital, you will be forced to go to prison or directly to the morgue[32].

Always fighting

Maasai woman grazing[33]

The Maasai ethnic group is of semi-nomadic origin, has its roots in the displacement along the lands of the Great Rift Valley (a vast valley with a unique ecosystem that stretches 6000 km and crosses the state of Kenya and Tanzania[34]) and their culture is based, long before they began to have agricultural settlements, on cattle breeding, hunting and the use of round houses (Boma) that are disassembled and reassembled in a few hours, following the tribe’s transhumance[35]. Cattle are companions in life and form the basis of the social organisation: the men take care of the cattle’s defence, the women of milking, as well as the house and children[36].

Cattle are a currency of exchange, they are the means to feed, to make utensils, clothing and blankets[37]. A head of cattle is given to a young warrior who, according to the community, shows sufficient courage in situations of community danger, and forms the basis of relations between clans: the more cattle a man has, the richer and more esteemed he is, and the better chance he has of having a wife[38]. The expropriation of land is a nightmare that endangers the core of the Maasai socialisation and economic system, not least because the lands expropriated are those with water sources, and what remains is no longer enough for the entire cattle[39].

The expansion of the market economy and private property change the savannah: in charge are owners who overexploit the land and have their herds reduced[40]. Lilian Looloitai[41], the indigenous representative who is fighting for funding from the international community[42] and for the creation of a non-profit organisation that promotes the rights of Maasai herders[43], explains: ‘We need to talk openly about the land issue. The government has not taken adequate measures to educate and communicate what its intentions are’. The evictees ‘are told: You cannot cross this land, it belongs to the government, you cannot cross that land, it belongs to the investors’. Nothing else. No indication of where to go[44].

These statements, dating back to 2017, refer to the disputes[45] that culminated in the destruction, by fire, of 185 Maasai homes in the space of just two days (13 and 14 August 2017); in addition to livestock theft, abuse, physical threats and absurd fines[46]. For several days, the Maasai population of that village, including women, children and the elderly, are forced to sleep without shelter, food and water; many families suffer forced separation and many of their members report severe psychological distress. It is estimated that at least 6800 people remain homeless due to the months-long violent eviction[47].

At the beginning of the 1990s, the journalist Stan Katabalo tried to engage international opinion on the allocation of the Loliondo hunting grounds, and was murdered for this on 26 September 1993[48]. One of the journalist’s collaborators, Ngorongoro MP Moringe Parkipuny, luckily survives an assassination attempt before leaving the country for good[49]. The scandal explodes equally around the illegal expropriations, the procedures for the allocation of blocks, the hunting practices carried out outside of all regulations, but above all for the special licence granted to the billionaire Mohammed Abdul Rahim Al-Ali, Vice-Minister of Defence of the United Arab Emirates and owner of the company OBC (Otterlo Business Corporation) [50], in addition to the mining licence granted to Barrick Gold and which is a disgrace we have already mentioned[51].

Hell Otterlo

Emirati hunters rape the fauna of wrongfully acquired territories[52]

Despite the fact that the constant human rights violations perpetrated in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area have been in the crosshairs of international interest for decades, Tanzanian ministers continue undisturbed to make illegal deals with the OBC company and their Emirati representatives[53], so that the abuses do not stop[54]. On the contrary: over the past decades, little by little, the Tanzanian government has traded the lives of endangered animals and the Masaai people for new high-tech weapons produced by Emirati industry[55]. An article in the New York Times of 13 November 1993[56] reports on the deal between TAWICO (Tanzania Wildlife Coorporation) and Mohamed Abdul Rahim Al Ali, then Deputy Minister of Defence of the United Arab Emirates[57].

The occupation by the OBC began in 1992, when Rahim Al Ali – who had already been venturing out on hunting trips here since 1985[58] – obtained a hunting concession from the Tanzanian government in the Loliondo Game Controlled Area reserve, on the edge of the Serengeti National Park, without the consent of the Maasai inhabitants. This is an area of 30,000 square kilometres (the size of Belgium) that is the largest area for the protection and survival of animal species native to sub-Saharan Africa[59]. In the Serengeti, as in every national park, human settlements and commercial activities are prohibited – the alibi the government uses to evict the Maasai: hunting and tourism are evidently too profitable to guarantee the exclusion of a certain elite.

Loliondo’s original concession on the border with the Serengeti limits safaris to three months a year, namely July, August and September, a limit that is not respected by Rahim Al Ali, but this is not the only abuse[60]. In addition to overriding the villagers’ consent, the exploitation of the hunting reserve is granted for a period of 10 years instead of the five years stipulated in the regulations, and all this after it was first granted to TAWICO, which managed the hunting blocks in Tanzania until the Wildlife Division was established in 1988[61]. The scandal emerged in 1993, when Mohamed Abdul Rahim started killing and transporting protected animals[62]. In fact, the agreement allows him to do so in return for a promise to invest part of the proceeds in the foundation of primary schools and hospitals[63]. Mohamed Abdul Rahim makes no secret of the fact that he goes hunting in the Serengeti because he wants ‘big cats like lions, leopards, cheetahs and other large carnivores’[64].

These hunters pay a tax (according to some sources 25% on the value of the prey[65]) to the local authorities: ‘The costs for the wildlife officials and their maintenance will be borne by His Excellency through the Central Wildlife Authority’[66]. Mohamed Abdul Rahim then obtains the displacement of entire Maasai villages with the aim of increasing tourism to the detriment of the ecosystem: for example, since 1993 there has been a 90%[67] decrease in the black rhino population. At the same time, over the decades, the human rights of those living in the areas adjacent to the Ngorongoro Crater have diminished[68].

Peter Poole, consultant to FPW (First Peoples Worldwide[69]), denounces ‘the corruption of local hunting guides, the exceeding of catch quotas, hunting inside the Serengeti, the use of automatic weapons during the hunt, the corruption of officials who give concessions and of politicians to prevent them from cancelling concessions’ and concludes: ‘It is this Arab who financed the whole operation’ referring to Mohamed Abdul Rahim Al Ali[70]. As the game dies out in one area, the Tanzanian army displaces the Masaai from the adjacent one and forces the herds into drought-stricken areas, killing them[71]. Into the liberated areas comes the big-cat hunting of luxury safaris[72] and, soon after, exclusive hotels[73].

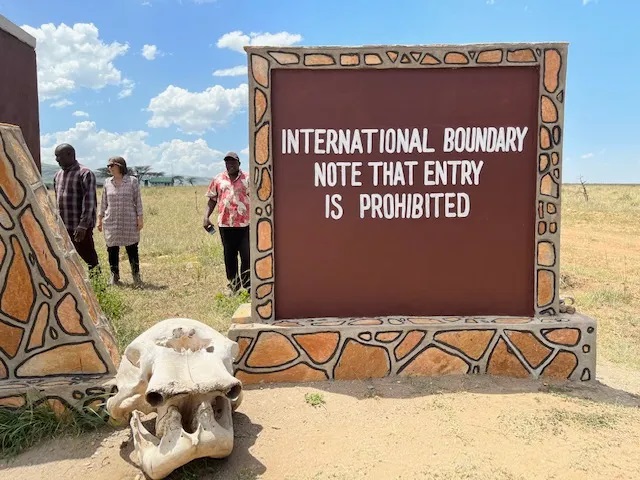

Stone marking the boundaries, patrolled by the police, of the areas wrested from the Maasai and handed over to the OBC[74]

The neighbouring state of Kenya banned big game hunting as early as 1978, but Tanzania fails to take a leaf out of its book: on the contrary, Tanzanian laws in favour of safaris date exactly from the enactment of the Kenyan ban[75]; over the years hunting rules have been established to ‘preserve’ the local fauna, but in the Loliondo Game Control Area they have never been respected[76]. Hunting activities that endanger the most important parks in East Africa, from the years of colonialism onwards, have never ceased[77]. The OBC hunts using forbidden practices: it creates transit channels by setting fire to the areas where the animals stay to make them move, while it pumps water into other areas to attract and capture them[78], and Tanzanian government bureaucrats deny this even in the face of evidence[79]. Juma Akida Zodikheri, CEO of OBC, maintains that the hunting activities respect Tanzanian laws[80].

Over the years, OBC’s presence grows, and it builds campsites, airstrips for aircraft, and mobile telecommunications infrastructure on Tanzanian soil[81], but it is no longer alone: companies such as the Americans’ Thomson Safaris[82] appear on the scene, and as early as 2010, it has been collecting complaints from herders against its subsidiary, Tanzania Conservation: they accuse it of practising illegal evictions[83]. But the company seems to enjoy special friendships, such as that of Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa[84]. Foreign companies obtain permits in exchange for donations to officials[85] and politicians[86]. Despite the efforts of the late President Magufuli, who created a Tourism Police Office to promote ‘safe tourism’[87], the will of the companies overrides that of the government[88].

Today there is a sign planted in northern Tanzania that marks the boundary of the Serengeti Park and forbids the Maasai to cross it; beyond that line is land that, according to the law, belongs to the local tribes, but is defended against them militarily[89]. According to journalist Todd Miller, the government’s hope is that the Maasai will cross the barriers and allow themselves to be massacred[90]. The two Maasai who accompany the journalist on the report show him the patrols of the military to defend what is commonly called the ‘Otterlo border’[91].

In the skin of the Maasai

Maasai suffer atrocious violence during forced evictions[92]

The commercial exploitation of the Serengeti obviously plays a decisive role for the nation as a whole: according to the World Tourism Organisation, tourism is an economic activity in Tanzania amounting to 10.7% of GDP[93]; in July 2022, the Deputy Commissioner of the Ngorongoro Protected Area claims to expect the arrival of around 1.2 million tourists per year, with a revenue of $112 million[94]. And in this case, we are talking about elite tourism, since the safari world attracts hunters willing to spend between $15,000 and $60,000 for a two- or three-week hunting trip, and the OBC is able to attract several hundred a year[95].

But all this is not enough to justify the gross violations of human rights and the destruction of the ecosystem. There is much more behind it. There is the trade in live animals, perpetrated on Tanzanian soil as early as March 1993[96], when the government authorised its partners in the Emirates to capture alive 10 generuk, a splendid species of long-necked antelope[97]. But the Arabs do not stop there, and capture zebras, gazelles and other protected species, in violation of Section 11 of the Wildlife Act No. 12 of 1974 – and they do so under the escort of police officers[98]. The ‘best’ customers, however, are the Chinese: in Tanzania, a flourishing ivory smuggling market operates in addition to drugs: between 2009 and 2014, a decrease of about 40% of elephants is reported, as the Chinese people value ivory tusks for precious ornaments and trophies[99]; it is estimated that at least 250 pounds of ivory can be obtained from each adult elephant, and then resold for USD 1500 per pound[100]. A trade also authorised by a Tanzanian government licence[101].

In March 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping, on his maiden voyage around the world, visited Tanzania, bringing with him a large political and business delegation: while he spoke of unity and cooperation, his entourage bought thousands of kilograms of illegal ivory, using the cover offered by their official status to do so[102]. In 2012, investigative journalist Aidan Hartley and his television crew managed to get consent to film what is considered the world’s largest store of ivory: tonnes of tusks waiting to cross the country’s borders and reach countries where they will be refined[103].

This hell has been known for a long time, as evidenced by the media campaign launched by Avaaz.org in 2012 with an open letter to the president of Tanzania[104]: ‘As citizens of the world, we call on you to oppose any attempt to evict the Maasai from their traditional land or to require them to relocate to make way for foreign hunters. We count on you to be a champion for your people and stop any attempt to change their land rights against their will’[105]. In just four days, on 13 August 2012, the petition reached more than 400,000 signatures, reaching 2 million[106]. In vain, of course[107].

In spite of this, the Maasai win an important case in 2018: the East African Court of Justice issues a ruling ordering the Tanzanian government to prevent anyone from exploiting the 1500 km2 area where the Maasai live[108]. The ruling expressly prohibits the Inspector General of Police’s office from carrying out evictions, from using harassment, intimidation and violence against the residents, prohibits the confiscation of their livestock or the destruction of their farms – and is thus an important acknowledgement of the facts hitherto denied by the government[109].

2012: Aidan Hartley in the storage of over 90 tonnes of ivory, worth $50 million[110]

The ruling remains a dead letter. On 11 January 2022, the government announced its intention to designate the 1500 square kilometre area of the Ngorongoro district as a wildlife corridor: if implemented, the creation of a wildlife corridor would lead to the Maasai losing their land permanently, as the plan calls for the displacement of more than 70,000 people, forcibly settled at Msomera, in Handeni District, and Kitwai, in Simanjiro District, both several hundred miles away[111]. According to the United Nations, the Maasai affected by the threats of displacement from Loliondo and Ngorongoro number as many as 150,000, and the implementation of the government’s plans ‘could jeopardise the physical and cultural survival of the Maasai’[112].

What is astonishing is the indifference of the international community: the executive director of the Oakland Institute accuses UNESCO of even being complicit, because it does not use its influence to ensure that the rights of the indigenous people are respected[113]. According to the director of the Oakland Institute, UNESCO ‘is nothing more than a Western colonial-minded, top-down agency that talks about preserving places without people, and instead of preserving culture, supports the cemetery of culture, extinguishing the way of life and livelihood’[114]. True. The violence does not stop. These areas are war zones: subsidies and services in the Ngongoro and Misigiyo areas for water and schooling are suspended, staff reductions in hospitals are ordered to make it increasingly difficult for citizens to receive treatment[115].

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority continues to send eviction notices under the pretext of fighting illegal immigration. It calls for the destruction of houses, churches, schools, medical dispensaries and administrative offices, including a police station, because according to the agency they are built without permits – provisions fortunately now stopped by protests[116]. The authorities are doing ‘scorched earth’, trying to make the region unliveable. The government defends itself by asserting that, in fact, the opposite is true: the Maasai and their herds are expanding like wildfire and now pose a threat to the conservation of the Ngorongoro and Serengeti, endangering the ecosystem[117].

But this is clearly a colossal lie. The Maasai are a people who have always lived in total harmony with nature, as well over 250 scientists and conservation experts claim in an open letter calling for a permanent halt to the evictions[118]. If this is done, in a few years Tanzania’s wildlife will be erased from history, or it will remain an exclusive luxury only for those who are extremely rich and can afford to spend their holidays in one of the most beautiful lands in the world, defended by an army of torturers who have slaughtered anyone who dared to be born there – no matter whether man or beast.

[1] https://news.mongabay.com/2022/06/maasai-protesters-shot-beaten-as-tanzania-moves-forward-with-wildlife-game-reserve/

[2] https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/maasai-tanzania-are-being-forcefully-evicted-their-ancestral-lands

[3] https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/maasai-tanzania-are-being-forcefully-evicted-their-ancestral-lands

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jun/14/maasai-leaders-arrested-in-protests-over-tanzanian-game-reserve, https://www.survivalinternational.org/news/13051

https://www.lindipendente.online/2022/02/25/la-tanzania-sta-cercando-di-cacciare-i-maasai-dalle-terre-ancestrali/

[5] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[6] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[7] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[8] https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Tanzania_Colonial_Records#:~:text=British%20Colonization%20(1919%2D1961),part%20of%20the%20territory%20Tanganyika.

[9] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[10] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[11] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/39/

[12] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/39/

[13] https://www.masaimara.com/

[14] https://www.samburureserve.com/

[15] http://www.kws.go.ke/amboseli-national-park

[16] https://www.nairobinationalparkkenya.com/

[17] https://www.tarangirenationalparks.com/

[18] https://www.lakenakurukenya.com/

[19] https://www.serengeti.com/

[20] https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/

[21] https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5512/

[23] https://achpr.au.int/en/news/press-releases/2023-02-24/press-statement-promotion-mission-united-republic-tanzania

[24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R3kG0YJ5_s&t=627s

[25] https://lens.civicus.org/tanzania-maasai-people-resist-forced-evictions/

[26] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jun/23/tanzania-charges-20-maasai-with-after-police-officer-dies-during-protests

[27] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/11/tanzania-masaai-evictions/#:~:text=On%2010%20June%2C%20security%20forces,Maasai%20also%20suffered%20gunshot%20wounds.

[28] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/11/tanzania-masaai-evictions/#:~:text=On%2010%20June%2C%20security%20forces,Maasai%20also%20suffered%20gunshot%20wounds.

[29] https://www.ipsnews.net/2017/08/forced-evictions-rights-abuses-maasai-people-tanzania/

[30] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/11/tanzania-masaai-evictions/#:~:text=On%2010%20June%2C%20security%20forces,Maasai%20also%20suffered%20gunshot%20wounds.

[31] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jun/23/tanzania-charges-20-maasai-with-after-police-officer-dies-during-protests

[32] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/11/tanzania-masaai-evictions/#:~:text=On%2010%20June%2C%20security%20forces,Maasai%20also%20suffered%20gunshot%20wounds.

[33] https://www.nature.org/en-us/magazine/magazine-articles/survival-in-the-great-rift/

[34] https://sites.google.com/site/benvenutiinkenya/great-rift-valley

[35] https://www.siyabona.com/maasai-tribe-east-africa.html

[36] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cattle-economy-maasai/

[37] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cattle-economy-maasai/

[38] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cattle-economy-maasai/

[39] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cattle-economy-maasai/

[40] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cattle-economy-maasai/

[41] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/oct/16/land-means-life-tanzania-maasai-fear-existence-under-threat

[42] https://forestdeclaration.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/NYDF-Endorser-Perspectives-Report_EN.pdf P. 49

[43] https://talks.ox.ac.uk/talks/id/7cad4ba9-733c-427b-b8e1-e3794bd63c9c/

[44] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/oct/16/land-means-life-tanzania-maasai-fear-existence-under-threat

[45] https://www.iwgia.org/en/

[46]https://www.iwgia.org/en/tanzania/2502-tanzania-forced-evictions-of-maasai-people-in-loliondo

[47] https://www.iwgia.org/en/tanzania/2502-tanzania-forced-evictions-of-maasai-people-in-loliondo

[48] https://justconservation.org/the-corridor-loliondo

[49] https://justconservation.org/the-corridor-loliondo

[50] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2015/12/obc-hunters-from-dubai-and-threat.html

[51] https://ibiworld.eu/2020/09/04/oro-cianuro-e-sangue-nellinferno-della-barrick-gold/

[52] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2015/12/obc-hunters-from-dubai-and-threat.html

[53] https://justconservation.org/the-corridor-loliondo

[54] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/

[55] https://www.zawya.com/en/press-release/companies-news/edge-signs-cooperation-agreement-with-the-tanzania-peoples-defence-force-jkca1731

[56] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[57] https://justconservation.org/the-corridor-loliondo

[58] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2015/12/obc-hunters-from-dubai-and-threat.html

[59] https://www.serengeti.com/

[60] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2015/12/obc-hunters-from-dubai-and-threat.html

[61] https://www.maliasili.go.tz/sectors/category/wildlife

[62] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[63] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[64] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[65] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2015/12/obc-hunters-from-dubai-and-threat.html

[66] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[67] https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/13/opinion/the-brigadier-s-shooting-party.html

[68] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2023/02/the-tanzanian-government-commandeers.html

[69] https://www.colorado.edu/program/fpw/

[70] https://ictnews.org/archive/conservations-new-breed-of-refugee-is-all-too-familiar-to-indian-country

[71] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/30/maasai-game-hunting-tanzania

[72] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/

[73] https://secure.avaaz.org/page/en/

[74] https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/02/10/the-crisis-nobody-knows-about-on-the-kenya-tanzania-border/

[75] https://ntz.info/gen/n01526.html

[76] https://ntz.info/gen/n01526.html

[77] https://ntz.info/gen/n01526.html

[78] https://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/den-tredje-verden/masaier-presses-af-luksusj%C3%A6gere

[79] https://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/den-tredje-verden/masaier-presses-af-luksusj%C3%A6gere

[80] https://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/den-tredje-verden/masaier-presses-af-luksusj%C3%A6gere

[81] https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/oped/why-the-loliondo-controversy-refuses-to-go-away-3857240

[82] https://thomsonsafaris.com/

[83] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/thomson-safaris-lawsuit-re-maasai-in-tanzania/

[84] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2022/03/ndumbaro-tells-dangerous-lies-about.html

[85] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2018/04/loliondo-between-silence-confusion-fear.html

[86] https://josephatlukaza.blogspot.com/2018/04/obc-yatoa-magari-15-kwa-wizara-ya.html

[87] https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/magufuli-opens-police-station-to-promote-secure-tourism-2630006

[88] https://josephatlukaza.blogspot.com/2018/04/obc-yatoa-magari-15-kwa-wizara-ya.html

[89] https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/02/10/the-crisis-nobody-knows-about-on-the-kenya-tanzania-border/

[90] https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/02/10/the-crisis-nobody-knows-about-on-the-kenya-tanzania-border/ ; https://news.mongabay.com/by/john-c-cannon/

[91] https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/02/10/the-crisis-nobody-knows-about-on-the-kenya-tanzania-border/

[92] https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1394407531052113&set=pcb.1394399351052931

[93] https://www.vaticannews.va/it/mondo/news/2022-11/tanzania-maasai-sfratto-cratere-ngorong-nigrizia-intervista.html

[94] https://www.vaticannews.va/it/mondo/news/2022-11/tanzania-maasai-sfratto-cratere-ngorong-nigrizia-intervista.html

[95] https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/oped/why-the-loliondo-controversy-refuses-to-go-away-3857240

[96] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2018/04/loliondo-between-silence-confusion-fear.html

[97] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2018/04/loliondo-between-silence-confusion-fear.html

[98] https://termitemoundview.blogspot.com/2018/04/loliondo-between-silence-confusion-fear.html

[99] https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/fighting-ivory-trade

[100] https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/fighting-ivory-trade

[101] https://unitedrepublicoftanzania.com/economy-of-tanzania/investment-in-tanzania/chinese-investment-in-tanzania-trade-economic-relations-direct-investments-more/

[102] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/chinese-officials-accused-of-smuggling-ivory-during-state-visit-to-tanzania/2014/11/06/ecea6ef7-f68d-4344-9865-0095b1531c5f_story.html

[103] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/tanzanias-ivory-stockpile/

[104] https://secure.avaaz.org/page/en/

[105] https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/save_the_maasai/?slideshow

[106] https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/save_the_maasai/?slideshow

[107] https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/save_the_maasai/?slideshow

[108] https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/ruling-on-application-tuesday-180925.pdf

[109] https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/maasai-victory-east-african-court-justice-tanzanian-government

[110] https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/tanzanias-ivory-stockpile/

[111] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jan/16/tanzania-maasai-speak-out-on-forced-removals

[112] https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/06/tanzania-un-experts-warn-escalating-violence-amidst-plans-forcibly-evict

[113] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/27/tanzania-conservation-colonialism-eviction-indigenous-rights/

[114] https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/27/tanzania-conservation-colonialism-eviction-indigenous-rights/

[115] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jan/16/tanzania-maasai-speak-out-on-forced-removals

[116] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jan/16/tanzania-maasai-speak-out-on-forced-removals

[117] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/jan/16/tanzania-maasai-speak-out-on-forced-removals

[118] https://docs.google.com/document/d/12ZoN4Gl8Ifn6vgKExC1xgjSyX_RyadFekpVKcW-wvs0/edit

Leave a Reply