His name instils respect and awe in at least five generations of politicians, military personnel and entrepreneurs: Henry Kissinger, advisor to presidents, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1973 (for deciding the end of the Vietnam War that he himself had helped to unleash), will be 100 years old in 2023. A century in which he has been at the centre of world history, but not only for his role as US Secretary of State. The most important part of Kissinger’s career began at the end of the Second World War when, as a military intelligence agent in Germany, he enlisted many Nazi hierarchs (and helped others to disappear) in the ranks of companies, scientific laboratories, the army and American espionage.

His ‘forgotten’ biography speaks of how, from 1944 onwards, he patiently worked on the organisation of secret armies, coups, assassinations, and links between the US government, its most powerful (and most reactionary) lobbies, European neo-fascism and neo-Nazism, Freemasonry, the Vatican and even the Mafia. The justification for this plan that has cost incalculable deaths: to confront socialism and communism, everywhere, at any price. Kissinger, the son of a Jewish family that escaped Hitler’s persecutions, became the man who contributed to the survival of the heritage and human capital that was defeated in 1945, thus becoming the black soul of the new world order, which is only now falling apart to become, probably, something even more frightening.

This long article explains in detail his friendships, his alliances, his decisions, his intrigues: there you will find the most frightening names in the history of 20th century humanity. And him, always him, in the middle, coordinating the efforts of more than half a century of bloody American imperialism.

Choosing the best Nazis: Kissinger in World War II

The Kissinger brothers, Walter and Henry, visiting their hometown in Bavaria in 2019[1]

Our story begins and ends in southern Germany: Fürth is a small town in north-central Bavaria that, together with Nuremberg and Erlangen, forms the main conurbation of Middle Franconia[2]. Its historic centre miraculously survived the devastation of World War II, so today it is still possible to admire the old town hall, which was built in the mid-19th century in the image of the Old Town Hall[3].

In the 1920s, Falk Stern was a wealthy cattle trader and member of Fürth’s Jewish Orthodox bourgeoisie; when his daughter Paula married teacher Louis Kissinger, he helped them buy their first house[4]. Here, on 27 May 1923, the couple’s eldest son, Heinz Alfred Kissinger[5], was born; the young Heinz’s life passed (along with that of his brother Walter) cultivating a passion for football[6] and reading, until Hitler’s rise to power. From 1933 the situation changes radically: Louis loses his job, while Heinz (the future Henry) and Walter find it increasingly difficult to lead a normal teenage existence, experiencing segregation at first hand[7].

After the promulgation of the infamous Nuremberg Laws (1935) [8], the Kissingers began to look for a way to leave Germany; thanks to the financial support of a relative living in the USA, in August 1938 the family emigrated in the direction of New York[9] , three months before Kristallnacht (9-10 November)[10] , in which more than 1000 synagogues and 7500 Jewish-run businesses were destroyed or damaged all over Germany, as well as hospitals, schools, cemeteries and homes; about 30,000 Jewish men between the ages of 16 and 60 are arrested and taken to the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen[11].

After two years in the Bronx, the Kissingers found accommodation in the Washington Heights neighbourhood[12], also known as the ‘Fourth Reich’ because of the large number of German citizens (mainly Jews) living there[13]. In the years that followed Henry tried to build a social life for himself, managing to graduate and enrol at the local City College, where he took evening classes, working during the day in a brush factory[14]. In January 1943, almost 20 years old, Henry Kissinger is one of the 16 million men who receive the call to arms[15]. What for many is a curse, for Kissinger is an opportunity: noticed by his superiors at the Infantry Replacement Training Centre in Spartanburg (South Carolina) for the high scores he received in some tests, he is assigned to the Army Specialised Training Program (ASTP), a programme set up to send the most talented soldiers to university. He is sent by the ASTP to study engineering at Lafayette College (Pennsylvania), near his home in New York[16]. He became a US citizen on 19 June 1943[17].

When the need for troops from Europe led the Army to close the ASTP, Kissinger was sent to the 84th Infantry Division at Camp Claiborne (Louisiana) and, after several months of training, arrived in Germany on 2 November 1944[18]. While many of his fellow soldiers take up the rifle, Kissinger, a native German speaker, is assigned to the G-2 (Intelligence) section of the division command, later becoming a special agent of the CIC (Counter-Intelligence Corps)[19]; during the Battle of the Ardennes (16 December 1944 / 25 January 1945[20] ). Kissinger worked undercover in the Belgian town of Marche-en-Famenne[21] , interrogating prisoners of war and identifying enemy spies[22].

Sergeant Henry Kissinger and his mentor Fritz Kraemer with American troops in the Ardennes (1944)[23]

Crucial in this context is his acquaintance with Fritz A. Kraemer: a German aristocrat who fled Germany in 1933, after completing his studies in Italy, he went to the United States in 1939, enlisted in the army after Pearl Harbour and was assigned by General Alexander R. Bolling to the headquarters of the 84th Division. As a non-Jewish German who chose to leave his country in open opposition to Hitler’s ideology, Kraemer carved out a place for himself in Military Intelligence, becoming known in the milieu for his lectures to soldiers on the degenerate nature of Nazi ideology.

During one of these lectures he was overheard by the 21-year-old Kissinger, who wrote him a letter to convey the importance that his words had aroused in him; a long association was born, destined to have a decisive influence on Kissinger’s life[24]. In Germany, Kraemer procures for him the assignment of interpreter for General Bolling and, as Sergeant in the counter-espionage unit of the 84th[25] , favours his inclusion in the list of administrators of the city of Krefeld, occupied on the 2-3 March, 1945[26].

According to the SHAEF Public Safety Manual on Procedures, Military Government for Germany, the task of selecting local administrators to restore the functioning of the German public machine is assigned to the special departments of the military government’s public safety unit; in the absence of these units, in Krefeld it is the CIC officers who deal with recruitment and dismissal; Kissinger is among them, although his role has never been fully clarified. At this juncture he, by virtue of his intellectual qualities and his cultural and linguistic knowledge of the occupied country, may have made an important contribution in translating the documents that the Nazis had not been able to destroy before the escape[27].

After taking part in the liberation of the Ahlem concentration camp[28], Kissinger, now a member of the CIC with the rank of sergeant[29], arrived with his division in Hanover in April 1945; here, the CIC commissioned him to flush out Nazis and Gestapo members, a task in which he distinguished himself by exploiting his knowledge of German character, obedience and pride. For this assignment he receives the Bronze Star[30]. His services in Krefeld and Hanover earned him the post of district commander of Bergstraße in Bensheim, Hesse.

The task of the CIC is to protect the US forces from espionage, sabotage and subversion, arresting members of the SS, the SD (Sicherheitsdienst des Reichführers-SS, the spy agency of the SS and the Nazi party[31]) and some members of the Nazi party; at the same time, members of the Counter Intelligence Corps detain German General Staff officers in special interrogation centres and help to search for the best scientists in order to make their services useful to the US cause[32]. Kissinger (CIC Team 970-59[33] ), commander of the detachment based in Bensheim, becomes the absolute ruler of the town: he drives around in a white Mercedes confiscated from a Nazi and resides in a 1930s mansion (also confiscated) in an upscale suburb and, above all, has greater power than the military government, which includes the power to freely arrest people[34].

In April 1946, the army moved Kissinger from Bensheim to Oberammergau, a small town in the Bavarian Alps, where the U.S. Military’s European Command Intelligence School was located[35]; here he met Kraemer, one of the founders of the institute, who wanted him there to work as an instructor to educate soldiers about German society, to better track down the Nazis and restore the functioning of civil institutions[36]. Kissinger’s students included future Harvard professor Henry Rosovsky[37] and Helmut Sonnenfeldt, Kissinger’s assistant in the National Security Council (1969-74) and the State Department (1974-77)[38].

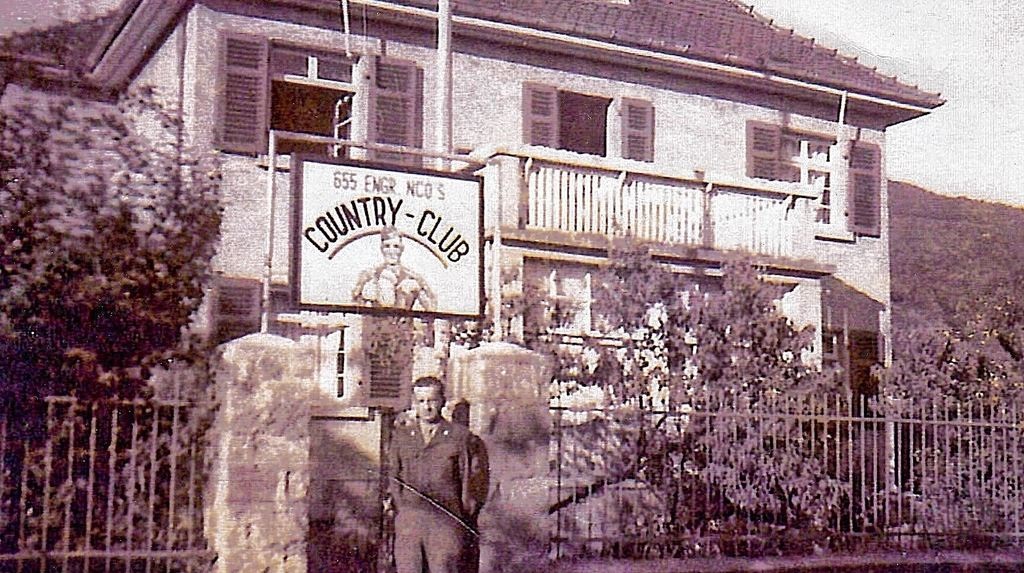

The US General Headquarters in Bensheim, where Kissinger served from 1945 to 1946[39]

Oberammergau’s proximity to several mountain hideouts of fleeing Nazis allowed military counter-intelligence agents to capture, among them, a number of elements considered valuable to the United States, organising their transfer to American territory, where they would become part of the post-war defence forces; the most famous of these transfers is that of Wernher von Braun: under the Nazi regime he is one of the main figures in the missile development programme, who in the USA, together with other eminent German scientists, makes an essential contribution to the development of missile programmes over the next twenty years[40], including Apollo[41].

Kissinger and Kraemer are aware of these activities[42], which are known as Operation Paperclip: more than 1,500 scientists and technicians with their families are secretly transferred to the USA[43] , under the guidance of the Rockefeller family’s lawyer, Allen Welsh Dulles[44] , who at the same time hires Reinhard Gehlen, a former spy in the service of the Führer, to enlist SS and Gestapo veterans in a new secret agency, the Gehlen Organisation (Gehlen himself later becomes director of the BND, the West German secret service), financed by the USA, which acts in concert with the newly formed CIA[45], leaving the ex-Nazis to set up secret structures such as Odessa[46] and Die Spinne[47] (the spider). These networks lead to the Ratline, an escape route to Argentina (with false documents provided by Gehlen and the CIA) for thousands of Nazi war criminals wanted by Israel, Russia, France, and other countries[48]. Among Gehlen’s collaborators stands out the name of Youssef Nada, who from Tangier organised the boat trips and false passports for the hierarchs on the run and[49], many years later, would be involved, with his Bank Al-Taqwa, in the investigations into the financing of the September 11 attack on the Twin Towers in New York[50].

These included such notable figures as Adolph Eichmann, the notorious Dr Joseph Mengele, Otto Skorzeny [51], Walther Rauff, Friedrich Schwend and Klaus Barbie – all of whom worked for the CIA-BND as advisors to the dictators of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Bolivia, running torture centres, death squads and cocaine rings[52] as part of Operation Condor[53]. In 1947 Henry Kissinger worked as a German translator in Military Intelligence, helping Dulles set up these secret networks through interrogations of top Nazi prisoners held by the US military, later absorbed by the CIA-BND[54].

Barbie, Schwend and Skorzeny initially worked for the CIC together with Kissinger[55], and were financed by him, in South America, to set up and run a group of companies involved in arms and drug trafficking: La Estrella SA group, headquartered in Peru (Friedrich Schwend) and branches in Argentina (Willem Sassen), Bolivia (Klaus Barbie), Ecuador (Alphons Sassen) and Paraguay (Hans Ulrich Rudel)[56] – all Nazi officers in the pay of the CIC first, and the CIA later[57]. The weapons, distributed to the Death Squads in the Latin American countries, came from the German trader Gerhard Georg Mertins and his MEREX group, active in SS foreign operations even during World War II[58]. Walther Rauff, in Colonia Dignidad, was responsible for the training of mercenaries engaged in the Death Squads[59].

Otto Skorzeny was sent by Hitler to free Benito Mussolini, who was imprisoned in the Abruzzi, and was the one who organised the espionage network of the Republic of Salò after 8 September 1943 – a network for which the young Italian fascist Licio Gelli[60] and some Spanish Nazis worked[61]. A few months later, Gelli and Skorzeny organised the escape to Argentina of Herbert Kappler, the Nazi officer who ordered the massacre of the Fosse Ardeatine to avenge the partisan attack on Via Rasella in Rome[62]. At the end of the war, and in the following months, Skorzeny and Gelli worked for the CIC like Kissinger, in a spy network within which grew the neo-fascist terrorist Stefano Delle Chiaie[63] , the founder of Avanguardia Nazionale[64] , who would later work for Gelli and the CIA in Italy, Argentina and Chile, contributing with terrorist actions to the so-called strategy of tension[65].

Propaganda and torture against socialism: Kissinger in the 1950s

12 September 1943: SS officer Otto Skorzeny next to Benito Mussolini, whom he had just liberated[66]

In July 1947 Kissinger returned to the United States: he was accepted at Harvard, where he met William Y. Elliott, the second great mentor of his youth. Elliott is a legendary professor of history and political science, a fervent anti-communist, who in his thirty-eight years directed the doctoral theses of future leading politicians, including Pierre Elliott Trudeau (Canadian Prime Minister, father of Justin, who also became premier), Ralph J. Bunche (Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1950 and Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations). As his tutor in Harvard’s Government Department, Elliott introduced Kissinger to the study of European philosophy (Homer, Spinoza, Kant, Hegel)[67], appreciating in his protégé, like Kraemer, a great sense of history as a panacea against nihilism and conformism, as well as a set of instructions for future action[68].

In the late 1940s Elliott was staff director of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs and Foreign Aid; he was also a member of the Policy Planning Board of the NSC (National Security Council)[69]. Close to Richard Nixon since the late 1950s, he wrote the campaign speeches that Nixon himself narrowly lost to Kennedy in 1960, and was later a senior advisor at the State Department under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson[70]. Dean of the Harvard Summer School from 1950 to 1960[71], Elliott supported Kissinger to the point of putting him in charge of a project that indelibly marked the young man’s career: The International Seminar.

This was envisaged by Kissinger as an opportunity for brilliant Europeans who, for wartime and economic reasons, had not had the opportunity to get to know the United States, through which they could learn about the best side of the USA at a time when there was a strong need to remove as many promising minds from Communism as possible[72]. After the first seminar in 1951, Kissinger and Elliott founded Confluence, a newspaper that gave voice to the demands and discussions that emerged during the event[73].

Through Confluence, Kissinger’s name reaches the pages of the New York Times for the first time[74]; over the years, Europeans are joined by students from Africa, Asia and Latin America, increasing the resonance of the debate generated by the seminars. The journal acquired a notoriety unthinkable for an academic publication, gathering contributions from prominent political and cultural figures such as McGeorge Bundy, Hannah Arendt, André Malraux, Alberto Moravia and Denis Healey[75]. The search for funds to keep the project alive took up most of Kissinger’s time at the time. The money needed came from the university and the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, among others.

In 1967, nine years after the closure of Confluence, it was discovered that the CIA was among the main financiers of the newspaper and the International Seminar[76]: in 1953, a group called Friends of Middle East began making donations totalling just under USD 250,000. Kissinger has always denied knowing the CIA hand behind Friends of the Middle East[77]. The Farfield Foundation and other associations were also vehicles of the CIA’s continuous funding, which thus financially supported the Seminar’s lengthy project, an example of Cultural Cold War contributing to the creation of a common cultural identity, while at the same time providing Kissinger with valuable information on US allies, a fact that increased his prestige[78].

November 1958: Henry Kissinger and McGeorge Bundy (centre front row) in a group photo of members of Harvard’s Center for Institutional Affairs[79]

As director of the International Seminar, in 1952 Kissinger made a new trip to Germany, where Confluence was distributed (by virtue of a specific donation from the Rockefeller Foundation) in universities, party headquarters and the most important bookshops[80]; Shepard Stone, former journalist, member of US military intelligence in Germany during the war, Assistant Director of Public Affairs for Occupied Germany from 1949, from 1952 was Director of International Affairs at the Ford Foundation, working closely with the CIA to develop cultural projects around the world[81]. Kissinger was encouraged by Stone to continue the paper’s outreach to Europe’s intellectual elites[82].

After that trip, the PSB (Psychological Strategy Board) commissioned Kissinger to write a report that would form a basis for the committee’s work, aimed at immunising West Germany against the effects of Soviet propaganda, while ensuring the country’s lasting alignment with the common Western policy[83]. Active from 1951 to 1953, the PSB was an acting committee under the aegis of the National Security Council (NSC) with the task of coordinating programmes and operations with the CIA, the US State Department, certain branches of the Armed Forces and other agencies involved in psychological warfare[84]. The work of the PSB as a government propaganda machine reflects the urgency of not only relying on the network of international relations to preserve or change an international political situation, but to act by putting pressure on the masses[85].

The committee’s connections with the infamous illegal CIA projects dating back to the early 1950s (Bluebird, Artichoke and Mkultra)[86], which aimed at the mind control of individuals through the use of drugs and torture, leading the victims to confess in a first phase of interrogation; the second phase of this treatment involves the annulment of the victims’ will, turning them into unwitting killers, tools deprived even of the instinct for self-preservation[87]. The CIA of Allen Welsh Dulles, director of the Agency at the time, develops these projects with Nazi scientists belonging to the Gehlen Organisation, in fact continuing the work that they carried out at the time of the Third Reich in an anti-Allied function[88].

The PSB was established in April 1951 by US President Harry S. Truman, and consisted of the Under Secretary of State, the Deputy Secretary of Defence and the Director of the CIA (Presidential Directive on April 4, 1951)[89]. With the US leading the UN forces in Korea, the purpose of the committee is to avoid the development of rivalries between agencies involved in psychological operations[90]. Kissinger is one of the advisors to the PSB[91]. His report for the committee appears very pessimistic about the state of US-German relations, the spiritual unity of the West and Germany’s capacity for moral regeneration, perceiving the Soviets and the Americans as two sides of the same coin, warning that the power to influence events in a key country for US efforts in Europe is rapidly slipping out of US hands; also as a result of Kissinger’s words, the PSB approves the creation of a National Psychology Strategy Plan specifically for Germany, to be integrated into the overall plan for Europe[92].

Kissinger, in his book “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy” (1957)[93] , makes a severe criticism of the United States’ political passivity towards the Soviet positions on the subject of satellite states, German reunification and arms control, permitted by the United States’ announcements not to use force except in response to aggression[94]. With particular reference to the German situation, Kissinger accused his own government of not considering the question of European defence as a psychological problem, but only a technical one, denying its support for the reunification process, which could lead West Germany to listen to Moscow’s proposals[95].

18 July 1951: Gordon Gray (right) swears in President Harry Truman (left) as director of the Psychological Strategy Board torture centre, with which Henry Kissinger collaborated[96]

At the root of this criticism was the attitude held by the United States at the time, the result of which was the Geneva Summit in 1955 (also attended by France and Great Britain), at which the Soviets launched the Two-State Theory with Chruščëv, effectively sanctioning the impossibility of rapid German reunification[97], and rejected US President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s proposal called Open Sky, which envisaged cross-checking air control of the respective territories to verify the adherence of the US and USSR to arms agreements[98].

In 1955, Kissinger was invited as a consultant to a conference organised in Quantico (VA) by Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, then President Eisenhower’s Special Assistant for Foreign Affairs, to take stock of the US psychological strategy following the Geneva Summit[99]. Here he proposed to put pressure on the USSR through active support for German unification, which would force Moscow to come out of the closet and reject proposals to this effect. The US should work to keep West Germany in NATO and the WEU (Western Europe Union), supporting its economic growth through the establishment of an international economic development agency and the FRG’s entry into the EEC, planned for two years later, useful to complete the western alliance system. The Germans were to be induced to perceive Moscow with increasing clarity as the obstacle to their reunification aspirations[100].

In 1956, shortly after the Quantico meeting, Nelson Rockefeller offered Kissinger the direction of the Special Studies Project of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, a think-tank whose aim was to influence government strategies in international affairs[101]. In 1957, Kissinger’s book Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy was published (the result of his work at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, 1955-1956[102]), in which he outlined a precise critique of the Eisenhower presidency’s strategy of massive retaliation, announced three years earlier by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and contrasted it with the theory of Limited War, according to which the US, in order to implement an effective Cold War policy, would have to accept the possibility of limited recourse to nuclear weapons[103].

Released a few months after the Hungarian and Suez crises, the book sold 17,000 copies in its first year, ending up in the hands of then Vice-President Richard Nixon and, above all, in those of Eisenhower, who recommended the book to Dulles. Kissinger’s popularity exploded in October: after the successful launch of the Sputnik satellite, fear made Americans very willing to listen to new defence proposals: Nelson Rockefeller released International Security: The Military Aspect, a report written by Kissinger in 1955 following the Quantico meeting. After a television appearance by Rockefeller himself to present the contents of the book, the essay is requested in hundreds of thousands of copies[104].

Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller at a Trilateral Commission press conference[105]

Kissinger was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations from 1956 to 1977, later becoming its board member until 1981[106]. The fervent anti-communist Zbigniew Brzezinski, professor of international affairs at Columbia University and National Security Adviser to US President Jimmy Carter[107], is a member of the Council[108]. David Rockefeller [109], Nelson’s brother and owner of the Chase Manhattan Bank, set up the Trilateral Commission in 1973, of which Kissinger and Brzezinski are prominent members[110].

The Trilateral Commission is, officially, a forum on world affairs, composed of top-level personalities in the fields of business, finance and politics from North America, Western Europe and Japan, whose purpose is to promote international cooperation. In reality, the Trilateral Commission is said to be one of the organisations that secretly run the planet[111]. Among its members, in those years, there was only one Swiss: the Ticino financier Tito Tettamanti[112] , whose clients included Michele Sindona and other leading figures of that political season[113].

In 1975, the Commission’s political manifesto, entitled The Crisis of Democracy, was published, in which some of the group’s cardinal principles emerged, first and foremost pessimism and mistrust of western democracies, polluted by socialist influence. In order to avoid excesses of democracy, it would be desirable that where democracy does not apply, competence, seniority, experience and special talents can seize power; black participation in the political system is also a danger to democracy. It is argued that democracy is more of a threat to itself in the United States than it is in Europe or Japan, where there are still residual legacies of traditional and aristocratic values, which ensure the balance between democratic and undemocratic forces that is fundamental to governing a reliable country[114].

The birth of the ‘great UBS’: Kissinger and the GAF-Interhandel case

23 June 1937: IG Farben founder Hermann Schmitz (second from left) at a dinner with other board members[115]

In 1925, the five largest German chemical companies merged: Bayer, Hoechst, BASF, Agfa and Cassella and, together with other smaller companies, formed the holding company Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG, better known as IG Farben, which instantly became the world’s first chemical industrial group[116]. It was a project born out of the vision of the general director of the Metallgesellschaft industrial group, Hermann Schmitz: in 1931, he wrote ‘Deutschlands einzige Rettung’ (Germany’s Only Salvation), which incited the country’s business community to politically support and economically back National Socialism, which became the document on the basis of which IG Farben formed an alliance with Hitler[117].

Schmitz himself, who arrived at the head of the Metallgesellschaft during a period of economic recession due to the bankruptcy of some banks, theorised in 1906 about the creation of tax havens to save large companies and banks from bankruptcy[118]. During the First World War, he was called upon by Walther Rathenau to head the financial office of the KRA Kriegsrohstoffsabteilung (Kriegsrohstoffsabteilung), which for the first time used Swiss banks to buy raw materials to circumvent international sanctions[119].

With the advent of Nazism, IG Farben became instrumental in military strategy, patenting Tabun and Sarin in 1937 and 1938, two deadly types of nerve gas, the effects of which were tested in concentration camps[120]. To these was added Zyklon B: a pesticide that, rendered odourless, was used in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Degesch (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekampfung mbH), the manufacturer of Zyklon, is a 42.5% subsidiary of IG Farben[121]. The Monowitz work camp, part of the Auschwitz complex, was completed in 1942 to supply workers to the adjacent synthetic rubber production plant, and was built by IG Farben[122]; the technologies and technicians using them were transferred to the USA at the end of the war[123].

Standard Oil, founded by the Rockefeller family, had already been in business with IG Farben for some time when Hitler came to power. The Rockefellers then became valuable allies of National Socialism: the American company ceded several patents to IG Farben[124] that were useful for the technological development of the Third Reich’s war arsenal[125]. Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank managed the Nazi accounts in Paris, closing those of Jewish clients when Hitler came to power[126], and after the war was involved in the transfer of the Reichsbank’s assets to Swiss and South American accounts. Rockefeller’s ITT builds important communication systems for the Nazis; Rockefeller’s IBM builds machines for filing Holocaust victims[127].

In 1928, IG Farben founded IG Chemie in Basle: with a share capital of CHF 290 million, this became the largest Swiss company and the parent company of several holdings of the German giant in Europe and Latin America, as well as of the American IG Chemical Corporation, which was formed in 1929 in New York from the merger of several US companies of IG Farben[128]. IG Chemie procures low-interest capital from the Swiss financial system for the expansion of IG Farben, which maintains close control over the Swiss company by holding its unlisted ‘preferred shares’. Hermann Schmitz is elected president of both IG Chemie and IG Farben[129].

30 June 1925: The new headquarters of the Deutsche Länderbank in Frankfurt is inaugurated, which is controlled by BASF, then IG Farben, then sold after the war to UBS[130]

On IG Chemie’s board of directors are two distinguished representatives of Swiss high finance: Felix Iselin-Merian, board member of the Basler Bankverein, and Fritz Fleiner, professor of constitutional law and board member of the Kreditanstalt; also on the board are Carl Roesch, a German executive of IG Farben, the Basle banker Eduard Greuter and his brother-in-law August Germann-Greuter. The majority of the Greuter & Co. bank belongs to IG Farben[131] Felix Iselin-Merian is the brother-in-law of Johnann Rudolf Geigy-Merian, the founder of Ciba Geigy in Basel[132], a chemical company collaborating with IG Farben[133], which by now, after a series of mergers, is part of the multinational Novartis group.

In 1939, IG Farben, through IG Chemie, changed the name of its US subsidiary from American IG Chemical Company to General Aniline & Film Company (GAF); the board of directors included prominent American industrialists such as Edsel Ford, president of Ford Motor, Charles Mitchell, president of National City Bank[134], and Walter Teagle, president of Standard Oil[135]. The collaboration with Ford is also important because IG Farben holds a significant stake in Ford’s German plants.

Edsel’s father, Henry Ford, is much loved by the Nazis for his conspicuous financing of Hitler, for the leading role played by the German Ford – together with Opel (a German subsidiary of General Motors) – in the German armaments plan before and during the world war[136], and for his anti-Semitic book ‘The International Jew’ (1920)[137]. The change of name and the presence of American key men on the board of directors are elements of the Americanisation of GAF to avoid, with the approach of war, the feared seizure of the company by the US authorities. For this very purpose Hermann Schmitz resigned as company president in 1936, appointing his successor his brother Dietrich, who lived in the USA and was an American citizen.

After Schmitz left, the only obvious link between IG Farben and IG Chemie remained the GAF board member Felix Iselin-Merian. Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, IG Chemie was blacklisted by the British, as it was recognised as a German company; consequently, GAF also came under threat of seizure[138], with IG Chemie’s preference shares remaining in the hands of IG Farben. This still made it impossible to officially declare IG Chemie as the parent company of GAF: two fictitious Dutch subsidiaries of IG Chemie, Chemo and Voorindu, were in fact listed as reference shareholders.

On 10 May 1940, when Germany invaded the Netherlands, all Dutch activities in the United States, including GAF, were blocked by the Treasury Department, which controlled any financial transactions of the company from then on. In order to free General Aniline & Film from the yoke of the US government, it is necessary to declare that the real parent company of GAF is the Swiss IG Chemie, not its Dutch subsidiaries. Thus, the problem of preference shares, dividend guarantee options that the board of IG Farben exercises over IG Chemie, arises again[139].

30 July 1938: The founder of the car company of the same name, Henry Ford, receives the Grand Cross of the German Eagle from the German Ambassador in Washington, accompanied by a personal letter from the Führer[140]

Following pressure from GAF’s US advisors, Hermann Schmitz resigned as president of IG Chemie in the summer of 1940, IG Farben’s guarantee options were declared extinct, as were its share buy-back rights; the new president was now Felix Iselin-Merian; nevertheless, the Swiss Federal Council refused to offer IG Chemie diplomatic protection until the end of the conflict, implicitly not recognising it as a Swiss company[141]. GAF could however, at this point, answer questions from the US Securities and Exchange Commission about the identity of its parent company, stating that IG Chemie held 91.05% of its shares[142]. However, with the entry of the United States into the war, in 1942 GAF was confiscated as a German company used by IG Farben as a centre of espionage and its directorate was deposed[143].

At the end of the war, IG Farben was dismembered into BASF, Bayer and Hoechst[144], surviving as a legal entity, kept alive by compensation suits and property speculation. Although the company has been formally in liquidation since 1952[145], the story of IG Farben only ends with its official closure in August 2011[146]. Hermann Schmitz and the holding company’s top management were recognised as war criminals and ended up as defendants (and convicted) in the Nuremberg Trials[147]. IG Chemie was left with properties in Switzerland, Norway and the hope of getting back the confiscated GAF in the USA.

In the winter of 1945, IG Chemie changed its name to Internationale Industrie- und Handesbeteiligungen, abbreviated to Interhandel; Albert Gadow, managing director since 1935 and brother-in-law of Hermann Schmitz, resigned, leaving his post to the Swiss Walter Germann, nephew of the banker Eduard Greutert; These new attempts to sever ties with its origins did not convince the US government, which maintained the confiscation of GAF even after the end of 1946, when the US decided on the return of other assets prudentially seized from Switzerland[148].

In 1948, Interhandel filed a lawsuit against the US for possession of GAF shares, declaring itself a purely Swiss company. Washington, on the other hand, regarded IG Chemie/Interhandel as an offshoot of the German industrial sector, believing it right to use it to compensate the victims of Nazism, and asked the company to provide documents required under the Trading with the Enemy Act[149]. After the company’s initial assent to the request, the Swiss Federal Council forbade Interhandel and Bank Sturzenegger & Co. (the successor to Greutert & Co. after the death of Eduard Greutert) from producing documents, citing Article 49 of the Banking Act (banking secrecy) and Article 257 of the Criminal Code (prohibition of services for the publicising of sensitive economic data).

John Foster Dulles (centre) with his brother Allen, powerful advocates of war against the USSR[150]

From the early 1950s, Interhandel’s shares became the subject of increasing speculation on the Swiss stock exchanges, causing the price of an ordinary share to rise from 300 CHF in 1946 to 5450 CHF in 1960. However, the company continues to lose all its cases in the US due to missing documents, a fact that unnerves the small shareholders, who are stirred up by the trade press, which targets board members Iselin, Sturzenegger and Germann.

The turning point came at the hands of two brothers: John Foster Dulles is the nephew of Robert Lansing, US President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State[151], and the brother of Allen Welsh Dulles, the Rockefeller group’s lawyer and the first civilian to serve as CIA director (1953-1961)[152]. The Dulles brothers, lawyers at Sullivan & Cromwell, became financiers at the end of the First World War and played a central role in the structuring of German war reparations and loans to the Allies.

Sullivan & Cromwell’s clients included United Fruit, Standard Oil and International Nickel, companies variously involved in coups organised by the CIA after the Second World War; the Dulles were at the forefront of the large group of American industrialists and bankers eager to invest in Nazi Germany after Hitler’s rise to power[153]. In 1954, John Foster Dulles, at the time Secretary of State to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, entered the Interhandel issue, defending a bill proposed by Senator Everett M. Dirksen, which provided for the return of confiscated enemy property to its former owners: while acknowledging that the bill was in conflict with the 1945 Reparations Agreement, to which the US was a signatory, he declared that the agreement could not limit Congress’ power to deal with foreign property as it saw fit. Despite Dulles’ support, which dismayed the Allied countries, the bill was rejected thanks to opposition from the Justice Department[154].

In 1956, the Swiss Federal Council asked the International Court of Justice in The Hague to open arbitration proceedings over the Interhandel affair. A prerequisite for the opening of arbitration is the end of court proceedings in the USA. The trial in which the Supreme Court finally convicted Interhandel in early 1957, however, was remanded to the District Court in Washington for formal defects[155]. In June 1958, the US Supreme Court, overturning the rulings of the lower courts, reinstated the Interhandel case, entitling the company to be heard on the merits of the case even without the production of the Swiss documents.

Shortly after this decision, Interhandel put a new plan into action: Felix-Iselin, German and Sturzenegger resigned from the board of directors[156]. Charles de Loës (president of the Swiss Bankers Association) is the new chairman of the board of directors, while Eberhard Reinhard (manager of Kreditanstalt-Credit Suisse), Rudolf Pfeinninger (Schweizerischer Bankverein) and Alfred Schaefer (Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft, known in Italy as UBS) join as board members. Discouraged by the prospect of a protracted dispute with Washington, Reinhard and Pfeinninger resigned in 1959, leaving the field clear for Schaefer, who became managing director and vice-president of Interhandel[157].

An American satirical cartoon on GAF and Interhandel arbitration[158]

In the preceding months, the speculator Bruno M. Saager bought the majority of the company’s shares for UBS at a bargain price, later joining the board of directors[159]. The two bankers were not newcomers: as early as 1932, the UBS was already financially supporting the Pan-European Movement, created by Iselin-Merian and other Swiss pro-Nazis, and which proposed a single European customs area once Hitler had won the war[160]. Among the Americans who, after 1950, ensured the survival of the Pan-European Movement, its founder, Richard Nikolaus Coudenhove-Kalergi, counts only one name: that of Henry Kissinger[161].

Saager and Schaefer had the winning idea of changing their strategy towards the United States, also taking advantage of the changed international political climate: fifteen years after the end of the war, Washington’s enemy was the Soviet Union, no longer Nazi Germany; the past of General Aniline & film thus became less important. In the early 1960s Schaefer carried out an effective lobbying operation to try to convince the Kennedy administration to pursue an out-of-court settlement[162], which was reached after lengthy negotiations with the Justice Department, led by Robert Kennedy: despite the opposition of a large section of Congress and the GAF management, GAF was split between the US and Interhandel and its shares auctioned off at a profit of USD 320 million, of which USD 200 million went to the US and USD 120 million to Interhandel (around CHF 500 million at the time[163] )[164].

One of the reasons for the success of the operation is the great friendship between Henry Kissinger, who continues to settle matters relating to the confiscated Nazi assets, and the Swiss Ambassador Edouard Brunner – a friendship which, many years later, in 1979, would convince Switzerland to pay the ransom for 52 US citizen diplomats seized by Iran[165]. Brunner was, at the time of the Interhandel dispute, Switzerland’s Secretary of State and head of the staff responsible for negotiations with the US government and the International Court of Justice.

Patrick Martin, former head of the CIA in Switzerland, states in this regard: ‘Interhandel became a problem in 1957, when the Swiss Confederation filed a complaint with the International Court of Justice, arguing that it was a Swiss company and therefore not subject to the restrictions on the assets of enemy nations, and initiated seizure proceedings. The case was handled by the shrewd and patient Secretary of State Edouard Brunner, a close friend of Henry Kissinger, who together with Brunner and Brezinski had developed the theory of the ‘small step solution’ in anti-Soviet terms. Switzerland gained advantages from this strategy, provided it put up a united front against Moscow, closed its doors to all resources from Eastern Europe and reported the movements of Soviet agents on Swiss territory to Washington. Thus, in 1961, Brunner and Kissinger reached an agreement on Interhandel, after which Kissinger and Brezinski persuaded Robert Kennedy to sign the agreement to merge Interhandel with UBS”[166].

Having received the money from the Americans, Schaefer and Saager then proposed the merger of Interhandel with UBS in 1966, offering two UBS shares against one Interhandel share; the result was an increase in UBS’s share capital by CHF 60 million, in addition to the gain in Interhandel’s, which officially amounted to CHF 600 million (with some important holdings, such as that in Deutsche Länderbank – which became UBS’s German subsidiary – vastly undervalued). The merger completely changed the fortunes of the small Zurich bank, making it Europe’s largest institution at a stroke[167].

It may seem like a side event to the great human story, but it is not: with the transformation of UBS into a multinational colossus, Washington and Berne obtain, for almost half a century, control over the development of capitalism and politics in Western Europe, giving even tax evaders and money launderers the dignity of ideological partners of the Great American Dream and economic cronies of a very small number of multi-billionaires who, even today, make and unmake the fortunes of politicians and nations – a bombastic phrase that will become clearer when we talk about Gladio and the Years of Lead in Italy.

The Warlords: Kissinger and Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger: the President and his Secretary of State[168]

In 1955, with his entry into the Council of Foreign Relations, Kissinger began a close and fruitful relationship with Nelson A. Rockefeller, then special assistant for foreign affairs to President Eisenhower; for entry into the Council he was recommended by his dean at Harvard, McGeorge Bundy (he directed the Faculty of Arts and Sciences from 1953 to 1960[169]), who in 1958 offered him the position of associate director at the newly founded Center for the Study of International Affairs at Harvard, founded by Bundy himself thanks to donations from the Ford Foundation. Bowie, a professor at Harvard Law School and head of the policy planning staff of John Foster Dulles, President Eisenhower’s Secretary of State[170]. Bowie also shares with Kissinger experience at the Council of Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission[171].

Kissinger is a long-time friend of Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a historian and professor at Harvard who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1946 and 1966. When John F. Kennedy began his presidential term in January 1961, Schlesinger became one of his special assistants[172]; McGeorge Bundy took over as Kennedy’s National Security Adviser[173] and offered Kissinger a position as part-time adviser to the National Security Council, with the task of concentrating on the German question: Kissinger held the position until October 1961, maintaining contact with Schlesinger thereafter[174].

Under Bundy the National Security Council was overhauled, limiting the Council’s power in favour of that of the president’s personal staff, led by Bundy himself[175]. In 1962, Kissinger returned to Harvard as a professor and wrote foreign policy speeches for Rockefeller, with a view to his future presidential campaign[176] ; in 1964, Rockefeller (Governor of the State of New York from 1958 to 1973[177] ) lost the Republican primary to Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater[178].

In October 1965, Kissinger becomes advisor to the US Ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge [179], a position through which he soon carves out an important role in negotiating with North Vietnam, arriving in 1967 to obtain a first meeting in Paris with Mai Van Bo, North Vietnamese representative in France[180]. From National Security Adviser in the first Nixon administration and Secretary of State in the second, Kissinger remained personally involved in Vietnam War affairs until its conclusion[181].

On 20 January 1969, Kissinger began his assignment as National Security Adviser to the new President Richard M. Nixon: following the reforming line begun with John Fitzgerald Kennedy and continued with Johnson, Nixon entrusted Kissinger with a further shift in foreign policy within the White House through a new restructuring of the National Security Council, which saw the size of its staff tripled, becoming the main forum in which ongoing crises, operational problems and medium and long-term strategic planning were discussed[182].

April 1975: Henry Kissinger and President Gerald Ford during a session of the National Security Council[183]

Nixon’s primary interest in foreign policy is understandable in the international context of the period: the difficult situation of the Vietnam conflict seriously threatened to undermine the US position not only vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, but also China, Europe and South America. Kissinger and Nixon thus modified their concerns about the potential spread of communist governments in the world into an interventionist key: the ‘Kissinger Doctrine’ took shape[184]. which not only continued the war in Vietnam, but was also tested with a military campaign in Cambodia.

In April 1970, the US landed in the country, officially to hunt down Vietnamese communists, and in fact to ensure stability for the new government in Phnom Penh, which had emerged the previous month from a coup d’état staged by Lon Nol and Sirik Matak, the prime minister and his deputy[185]. The United States tried by all means to keep a loyal but totally inadequate government in place; the Khmer Republic, proclaimed by Nol in 1970, fell five years later, delivering a country devastated by civil war into the bloody hands of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge[186]. Lon Nol died in his Californian exile in 1985, having spent the million dollars he had taken from the Cambodian National Bank when he fled[187].

The attempt to restore fascism in Italy: Kissinger and the Years of Lead

2 August 1980: a bomb attack, ordered by the American secret services and Italian Freemasonry, destroys a wing of Bologna station, killing 85 people and injuring more than 200[188]

General Vito Miceli was, from October 1970 to 1974, head of the Defence Information Service (SID)[189], the Italian intelligence apparatus created in 1966 on the ashes of SIFAR[190]. He joined the P2 Masonic lodge in 1969 (membership card 491[191] ), after meeting Licio Gelli, who recommended Miceli to the Ministry of Defence, then headed by Mario Tanassi[192] , to replace Eugenio Henke as head of the SID[193]. He is a Member of Parliament, elected in the ranks of the MSI, from 5 July 1976 to 19 June 1979[194]. Graham Anderson Martin is American ambassador in Italy from 26 September 1969 to 10 February 1973, when he is sent to hold the same position in Vietnam[195].

In 1972, Martin pays General Miceli 800,000 dollars as the first instalment of an unconditional financing for the launch of a ‘propaganda operation’ which could have brought, had it not become public knowledge and therefore interrupted, 6 million dollars at Miceli’s disposal; this instalment is paid by Martin at the end of a long clash with the CIA’s Roman detachment, which was opposed to flooding a person with anti-democratic extreme right-wing ties with money. The US Congressional Commission of Inquiry investigating CIA covert activities also ascertains that Miceli received $11 million to give as electoral support to twenty-one political figures with clear anti-communist affiliations[196].

Approval for Martin’s plan came directly from Kissinger, then director of the NSC and head of the ’40 Committee’.[197] , secret organ of the Council which has the task of approving the most important undercover operations[198]. With that money, and with the approval of the P2 Lodge, Miceli set about creating a SuperSID. This secret agency, parallel to Stay Behind, has as its driving force the fierce anti-communism of its members and as its objective the destruction of any fertile ground for the rise of the communist party or left or centre-left forces to power; the aims of the parallel SID are pursued through the coordination of the activity of the neo-fascist terrorist organisation called the ‘Rose of the Winds’[199].

A coordination network of different subversive organisations, it is an evolution of previous experiences aimed at fomenting the activity of terrorist groups of anti-democratic or secessionist matrix[200], such as the Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol, a movement symbolic of South Tyrolean irredentism which, from 1956 to 1969, carried out a series of serious attacks in the Trento and Bolzano territories[201]. A key figure in the identification of the ‘Rose of the Winds’ in the courts is Colonel Amos Spiazzi, involved in the investigation into the Rose, who states that it was made up of military or ex-military personnel from all branches of the Armed Forces, trusted men belonging to the extra-parliamentary right, who could be counted on in the event of disturbances or attacks[202].

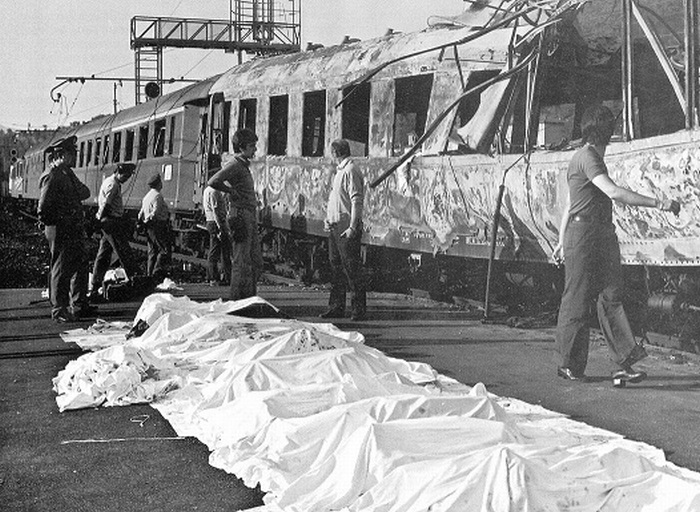

4 August 1974: the police collect the remains of the 12 victims of a bomb attack, ordered by the American secret services and carried out by Italian neo-fascists (Ordine Nuovo), which hits the Italicus train (carrying southern migrants to Munich) inside a tunnel[203]

Dario Zagolin is one of the leading right-wing figures in Veneto (and it is from the Prosecutor’s Office in Padua that the investigations into the ‘Rose’ begin[204]): in contact with Gelli, he brings together the regional neo-fascist groups with the National Front led by Giancarlo De Marchi: La Fenice, Ordine Nuovo, Avanguardia Nazionale (the organisation founded by another comrade-in-arms of Henry Kissinger, Otto Skorzeny and Licio Gelli: Stefano Delle Chiaie), the Giustizieri d’Italia and Carlo Fumagalli’s[205] MAR constitute the backbone of the ‘Rose of the Winds’[206].

Gladio is the name that Stay Behind takes on in Italy. Active since the 1950s, Stay Behind Net was created with the task of providing the countries of the Atlantic Alliance with a body capable of reacting promptly in the event of an attack by the Soviet Union and countries belonging to the Warsaw Pact, acting behind enemy lines with sabotage and guerrilla actions[207]. Gladio, like the organisations in the Netherlands, Belgium Luxembourg France, Switzerland, Norway and Austria, was created and managed under the control of the national secret services in conjunction with the United States, recruiting its agents also from among the civilian population[208].

The Italian magistrate heading the investigation into Gladio, Gianfranco Donadio, discovered that the financing of this structure was not only guaranteed by the American secret services, but also by a network of Italian and Swiss companies, one of which, FIMO SA of Chiasso, was at the same time the terminal for laundering money from the drug trade between South America and Sicily that was the subject of the investigations of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino[209]. This company, founded in the 1950s by obscure Genoese businessmen, has been recapitalised several times over the years by the UBS, through its manager Reto Kessler, an associate of Bruno Saager[210].

In addition to external attacks, Gladio’s task was to thwart internal threats aimed at destabilising the existing political balance, with particular reference to the communist danger; Vittorio Andreuzzi, an MSI sympathiser enrolled in Gladio in 1959, declares: “It was explained to us by the instructors that our organisation, which had to remain secret, would have to come into operation to counter communist street revolts. It was not said, except with brief hints, that the structure was also to serve to counter a foreign invasion. I remember with certainty that more than anything else, the trainers spoke of the need to prepare us to face the Italian communists and their subversive initiatives”[211].

From the acts of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into Terrorism, suspicions emerged on Gladio’s role in the implementation of the Demagnetize plan[212], planned by the PSB in 1951 (Kissinger began collaborating with the PSB in 1952) to weaken the Communist Party and the CGIL confederal trade union, ousting them from public administration circles and pushing for the approval of liberticidal laws on public security[213]. On 26 February 1991, the then Prime Minister, Giulio Andreotti, delivered to Parliament a list of 622 Italian citizens who belonged to Gladio[214]: among these were Francesco Cossiga[215] (Undersecretary of State for Defence in 1966, 1968, 1969, Minister of the Interior in 1976, 1978, Prime Minister in 1979, 1980, President of the Senate in 1983, President of the Republic in 1985-1992[216]), Paolo Emilio Taviani[217] (Minister of the Interior in 1962, 1963, 1973[218]), Giovanni de Lorenzo (general, head of SIFAR from 1955 to 1962[219]).

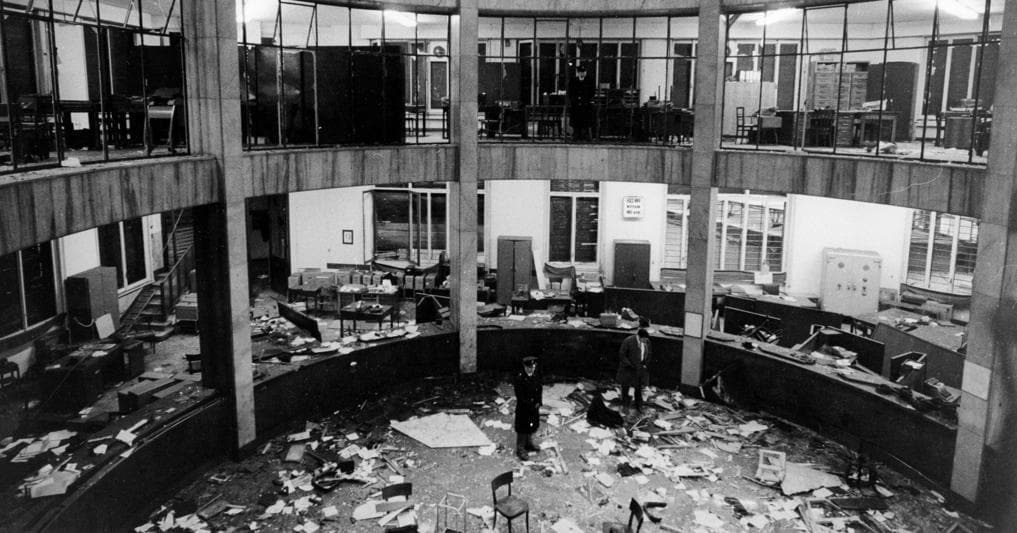

12 December 1969: a bomb planted in the Milan headquarters of the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura kills 17 people and injures 88: it is an attack by the neo-fascists of Ordine Nuovo, wanted by the CIA and Freemasonry[220]

From 1969, Gladio became an integral part of the Kissinger doctrine: thanks to CIA support, the organisation played a strategic role in the destabilisation of the country: in 1984, Vincenzo Vinciguerra, a former terrorist of Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale, responsible for the Peteano massacre (31 May 1972), heard by the judges in the Bologna Station massacre trial, describes the existence of a covert structure headed by NATO and supported by the secret services as well as by Italian political and military forces[221].

Gianadelio Maletti, general since 1971 in charge of department ‘D’ (counter-espionage) of the SID, speaks of the involvement of the CIA in massacres attributable to extreme right-wing groups, through the supply of the necessary material, such as the explosives used in the Piazza Fontana massacre[222]. Maletti, who was definitively sentenced together with Captain Antonio Labruna for deception in the Piazza Fontana trial[223], is a member of the P2 (Rome, 499)[224]. He was also sentenced to six years for failure to preserve secret documentation relating to the M.Fo. Biali in the Pecorelli murder trial[225]. Licio Gelli and the masonic lodge Propaganda 2 (P2) are undoubtedly privileged interlocutors of the United States in the implementation plan of the Kissinger doctrine through the strategy of tension, as testified by the ties that Gelli has since 1969 with General Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s personal assistant in the National Security Council[226].

The P2 received funding from the CIA to organise the fight against communism and the stabilisation of the country through its destabilisation. CIA agent Richard Brenneke claims to know Gelli well, described as a long-standing man of US intelligence[227]. In addition to the role played by the affiliates already mentioned, it is possible to deduce the participation of the lodge in destabilisation activities from the planned participation of its members in the attempted Borghese coup of 1970: Air Force General Giuseppe Casero (Rome, 488[228] ), Colonel Giuseppe Lo Vecchio (Rome, 514[229] ) and the lawyer Filippo De Jorio (Rome, 511[230] ), all of whom were charged for their participation in the event[231]. Gelli himself is alleged to have had, in the subversive project, the role of delivering the President of the Republic, Giuseppe Saragat, into the hands of the National Front (the formation led by Prince Junio Valerio Borghese[232] ), as he was in possession of a document allowing him free access to the Quirinale, obtained through the intercession of General Miceli[233].

The United States knew of Borghese’s Mafia involvement in the operation: Tommaso Buscetta states that he, having returned to New York after a stay in Sicily to learn details of the Mafia’s role in the coup, was arrested by the police and questioned about developments in the affair, which was secret at the time[234]. Ambassador Martin’s correspondence with the State Department and with Kissinger, Nixon’s National Security Adviser at the time, reveals the involvement in the coup of the top brass of the Italian Navy and Air Force, as well as confirming the US government’s direct knowledge of the project[235].

Through Italian-American businessman Pier Talenti, a personal friend of Nixon, and Selenia engineer Hugh H. Fenwick, the National Front established a relationship with the US leadership; in 1968, Talenti set up the Italian committee for the election of Nixon to the White House, of which Fenwick was also a member[236]; having collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in Rome from allies and friends, Talenti gained the President’s trust and the possibility of speaking to General Haig to warn of the danger of an imminent seizure of power by the socialists in Italy. He suggested the appointment of Graham Martin as new ambassador to Rome to counter the rise of the Left; the proposal met with favour from both Nixon and Kissinger, so Martin began his term in office in 1969[237]. In 1970, at the suggestion of doctor and National Front militant Adriano Monti, Fenwick approached Ambassador Martin to act as a direct link between the US administration and the coup plotters; the result was the conversation he had with businessman Remo Orlandini, a friend and important financial supporter of Borghese[238].

May 1972: Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti among the secret service officers later involved in the investigations into Gladio and neo-fascist attacks[239]

Of Lithuanian descent, that of the Archbishop of Orta and President of the IOR, Paul Casimir Marcinkus, is another name which links the Nixon administration to the P2 and the Sicilian Mafia: he comes into contact with the Sicilian financier, Michele Sindona (P2 card 501[240] ) and with Roberto Calvi (Milan, 519[241] ) thanks to his friendship with David Matthew Kennedy, President of the Continental Illinois National Bank of Chicago. In 1964, it emerged that the Continental International Finance Co., a subsidiary of the Continental Bank, owned 24.5% of the capital of Sindona’s Banca Privata Finanziaria (the merchant bank, linked to the Mafia, born from a rib of the Fasco AG of Vaduz, chaired by the Swiss financier Tito Tettamanti)[242].

The links between Kennedy and Sindona are evidenced by the latter’s participation as a partner in Kennedy’s Continental Finance, which put Sindona in touch with Charles Bludhorn, the rumoured patron of the Gulf and Western Industries conglomerate (hotels, oil wells, mines, the Paramount). Through his friendship with Bludhorn and Kennedy, as well as with Mafia bosses Vito Genovese and Joe Adonis, Sindona also became a financial adviser to Cosa Nostra.

The acquaintance between Marcinkus and Sindona through Kennedy came about when the prelate was not yet president of the IOR (the Vatican’s state bank), which, however, had a 24.5 per cent shareholding in Sindona’s Private Financial Bank since 1962, the year in which the financier took control of the Institute[243]. 1969 was a crucial year in the evolution of the affair: Kennedy was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by the newly elected President Richard Nixon, of whom he was a fervent supporter[244]; in June, Marcinkus was appointed President of the IOR[245]. In this way, Sindona has as partners in the Private Financial Bank his associates the US Secretary of the Treasury and the President of the IOR.

Through Sindona, Marcinkus gets to know the other piduist Roberto Calvi, president of Banco Ambrosiano, who in 1971 founds the Cisalpina Overseas Nassau Bank, owned by Compendium SAH of Luxembourg[246] and controlled by Sindona, Marcinkus and Banco Ambrosiano[247]. Marcinkus, Sindona, Calvi, but also Umberto Ortolani (financier and entrepreneur, prominent member of the P2[248], indicated in 2020 by the Bologna Public Prosecutor’s Office as one of the instigators of the massacre of 2 August 1980 [249]) and Licio Gelli: the desire to do business and acquire power is intertwined, in their case, with the aim of supporting those dictatorial regimes which, in South America, play a key role in the anti-communist strategy so dear to both the Italian right and the Nixon administration, with particular reference to Henry Kissinger, which is implemented in Operation Condor[250].

Calvi inaugurated in 1980 in Buenos Ayres, the headquarters of the Banco Ambrosiano de America del Sud[251] , in the country where Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera (P2 card: Buenos Aires, 478[252] ) and President Jorge Rafael Videla, protagonists of the blackest page of Argentine history, were in power. Massera is in relation with the Italian Admiral Giovanni Torrisi (P2 card: Rome, 631 [253]). Videla’s Argentina, thanks to Massera’s mediation, buys huge quantities of arms from Italy[254].

June 1978: Henry Kissinger (left) in conversation with Argentine dictator Jorge Rafael Videla, closely linked to Licio Gelli’s P2 Lodge[255]

Calvi opened other Ambrosiano offices in Peru[256], Brazil, Nicaragua[257] and Panama, while in Chile, Banco Ambrosiano had a shareholding in Banco Hypotecario, the largest financial group supporting Pinochet. In Guatemala, the Ambrosiano finances, through the company Brisa SA, the right-wing government of General Vernon, a former CIA agent. When the dictatorial regime of Somoza in Nicaragua went into crisis under Sandinista pressure in 1978, the Banco Ambrosiano subsidised the government to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars[258].

The enormous amount of money moved by the Vatican, the P2 Lodge, the Mafia and the CIA to South America serves to impose the yoke of military juntas loyal to the US government on the continent. When the population of one of these nations’ rebels, as in Allende’s Chile, the huge death machine is set in motion to smother the attempts of Latin American peoples to emancipate themselves in blood.

Neo-Nazi South America: Kissinger and the massacre of the Chilean people

February 1968: A self-disclosure session of the prisoners of the neo-Nazi institution Colonia Dignidad[259]

Operation Condor stems from the same concern that animates the moves of Nixon and Kissinger in Italy, reinforced by the victory of the socialist Salvador Allende in the Chilean parliamentary elections of 5 September 1970[260]. Before and after that date, the president and his advisor, who from the beginning of Nixon’s second term became Secretary of State, worked to undermine Allende’s position. The first attempt was through the US ambassador to Chile Edward Korry, who failed to prevent the victory of the socialists.

News came out in 1972 that ITT (International Telephone and Telegraph Corp.) – in which Nelson A. Rockefeller had a shareholding[261] – and the CIA had been collaborating since 1971 to damage Allende’s government through: a) recruiting collaborators in the Chilean armed forces to organise a revolt; b) pushing US companies to cooperate in order to provoke an economic storm in the country[262]; c) involving foreign governments in putting pressure on the Chilean government, also through diplomatic sabotage actions[263].

Already in the aftermath of Allende’s inauguration, Kissinger was pushing for the implementation of an intransigent policy towards Chile, fearing that the affirmation of the government in Santiago could serve as a model for others, such as Italy[264]. After General Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état (11 September 1973), which led to Allende’s death and the establishment of a military dictatorial regime, Kissinger applauded the new leader, despite being aware of the massacres perpetrated by the regime since the days immediately following the coup[265].

In December 1974, at a State Department staff meeting, Kissinger (now President Gerald Ford’s Secretary of State) firmly opposed Senator Edward ‘Ted’ Kennedy’s proposal to stop US military aid to the Pinochet regime; Kennedy’s proposal stemmed from growing pressure from human rights groups, an argument Kissinger reluctantly addressed because of the damaging consequences that failure to support the regime would have locally and generally, creating a dangerous precedent that could frustrate the work done to stop the feared ‘red advance’[266].

Kissinger’s trouble with the US Congress continued during 1975, when he met with Chilean Foreign Minister Patricio Carvajal, suggesting that he host the OAS (Organisation of American States)[267] meeting the following year and, by improving the regime’s image, change the US Congress’ attitude towards military assistance and facilitate the increase of Ex-Im Bank credits[268] and multilateral loans to Chile, as well as cash sales of military equipment[269].

11 September 1973: Salvador Allende, awaits the final attack by the rebel military, led by General Pinochet[270]

From the outset (1973), the Condor plan involved the secret service network of various Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador) in a secret collaboration with the CIA and the Washington government: this terror network allowed governments to send death squads into villages to kidnap, kill and torture real or supposed enemies, especially refugees from neighbouring states trying to escape persecution.

Condor takes state terror to a hitherto unknown level, unleashing it across South America, after successive (or previous, in the case of Brazil[271] ) right-wing military coups, often encouraged by the United States, had wiped out democracy across the continent. Condor is the detonator and fuel of a vast phenomenon that tens of thousands of people across South America were killed, disappeared or tortured by military governments in the 1970s and 1980s[272].

Operation Condor uses as its base a Nazi colony in Chile, directed by Dr Joseph Mengele, known as Colonia Dignidad: its founder, Walther Rauff, is a Nazi hierarch collaborator with Kissinger’s CIC, and is wanted in Germany for abducting and molesting young boys[273]. Colonia Dignidad was used by Pinochet’s team to train for the 1973 coup d’état, later serving as a torture centre where prisoners were ‘disappeared’. It is possible that many of South America’s most important Nazi war criminals lived in Colonia Dignidad[274]. In 1993, an archive of documents called the Archives of Terror was found in Paraguay, detailing the involvement of Nazi war criminals (most of whom came to the American continent as part of the Ratline escape project) in Operation Condor and listing the victims, including Israeli agents who were trying to find Nazis to try[275].

It is highly likely that George Bush senior (then CIA director[276]) also collaborated with Nixon and Kissinger in directing Operation Condor. It is now historically established, however, that Junio Valerio Borghese and Licio Gelli prepared for the coup d’état by attending a training course at Colonia Dignidad[277]. The history of this training centre, an extreme offshoot of SS activities during the Second World War, was only possible thanks to the cover of governments friendly to American power – and thus of the conglomerate consisting of the CIA, the NSA, the Secretariat of State and the Presidency of the Republic. In or alongside each of these positions, during all the years of US imperialist terror, there was always one person, Henry Kissinger.

1954: Diego Rivera’s mural depicts John Foster Dulles shaking hands with the dictator of Guatemala, Carlos Castillo Armas; next to him is his brother Allen. The bomb on which Dulles rests his hand has the face of Eisenhower[278]

When his bosses are dragged into court, there is a banker who pays for the best lawyers to defend the memory of Colonia Dignidad: he is the Swiss François Genoud, a personal friend of Stefano Delle Chiaie and Henry Kissinger[279] , who participated in the financing of the transfers of Nazi hierarchs carried out by Kissinger’s CIC with the money he received, over the years, from the NSDAP, and with the publication of Joseph Goebbels’ diaries[280] and of many rare and original documents that, at the end of the war, he had received as a gift from one of Adolf Hitler’s most trusted friends, SS officer Martin Bormann[281]. As you can see, over the years it is always about the same people, the same circle of friends, the comrades of the same Nazi paramilitary organisations.

In a few months he will be 100 years old. In his own way, he is a monument, the last surviving potentate among those who, during and immediately after the Second World War, were instrumental in constructing the Cold War era and managing it with an iron fist similar to that of Josip Stalin. The Bolshevik dictator committed unspeakable crimes against his own people. Kissinger and his accomplices sowed death and destruction all over the world, calling Western Europe to pay a very high tribute in exchange for military protection and the Marshall Plan boost. But that is another story. The telling of the true story of the years between 1945 and 1973 – that is, between the boom and the end of industrial capitalism – only begins now, from the man who was its most powerful, most pragmatic, most unscrupulous, most cynical interpreter. It is only right that it should be known, before his death turns him into an icon.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/27/business/walter-kissinger-dead.html

[2] “Ballungsraum Nürnberg – Fürth – Erlangen”, Entwurf einer kulturlandschaftlichen Gliederung Bayerns als Beitrag zur Biodiversität, Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt, 2011

[3] https://www.nordbayern.de/region/fuerth/furths-rathaus-lockte-nach-italien-1.8180298

[4] Thomas A. Schwarz, “Henry Kissinger and American Power” – a political biography, Hill and Wang, New York, 2020, p. 15

[5] Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, p. 20

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/soccer-germany-kissinger-idINDEE88E05Q20120915

[7] Niall Ferguson, “Kissinger: The Idealist, 1923-1968”, Penguin, New York, 2015, p. 67

[8] https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2010/winter/nuremberg.html

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/1975/12/16/archives/kissinger-visits-home-town-gets-big-hand-kissinger-visits-home-town.html

[10] https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/text/nazi-telegram-instructions-kristallnacht-november-10-1938

[11] https://www.britannica.com/event/Kristallnacht

[12] https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/16/nyregion/p-kissinger-97-the-mother-of-a-statesman.html

[13] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/henry-kissingers-world-war-ii/

[14] https://achievement.org/achiever/henry-kissinger-ph-d/

[15] http://www.world-war-2.info/casualties/

[16] http://www.pierce-evans.org/ASTPinWWII.htm

[17] [17] https://www.fpri.org/contributor/henry-kissinger/

[18] https://www.sfasu.edu/heritagecenter/9809.asp

[19] https://www.pbs.org/thinktank/transcript1138.html

[20] https://www.liberationroute.com/it/stories/129/battle-of-the-bulge

[21] https://visitmarche.be/en/categorie/offres-en/show-en/offre/11145/ ; Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, p. 48

[22] https://www.gijewsfilm.com/interviews/henry-kissinger.php#:~:text=In%20this%20capacity%2C%20Kissinger%20served,of%20the%20town%20of%20Hanover.

[23] https://www.globalo.com/why-kraemer-and-kissinger-split/

[24] Jeremi Suri, “Henry Kissinger and the American Century”, Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 78

[25] Holger Klitzing, “The Nemesis of Stability: Henry A. Kissinger’s Ambivalent Relationship with Germany”, WVT, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2007, p. 46

[26] Holger Klitzing, “The Nemesis of Stability: Henry A. Kissinger’s Ambivalent Relationship with Germany”, WVT, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2007, p. 44

[27] Holger Klitzing, “The Nemesis of Stability: Henry A. Kissinger’s Ambivalent Relationship with Germany”, WVT, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2007, pp. 47-48

[28] https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/kissinger-on-liberating-ahlem-concentration-camp

[29] Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, p. 48

[30] https://army.togetherweserved.com/army/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApps?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=372781&binder=true

[31] https://portal.ehri-project.eu/authorities/ehri_cb-006504

[32] Holger Klitzing, “The Nemesis of Stability: Henry A. Kissinger’s Ambivalent Relationship with Germany”, WVT, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2007, p. 52

[33] Holger Klitzing, “The Nemesis of Stability: Henry A. Kissinger’s Ambivalent Relationship with Germany”, WVT, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2007, p. 51

[34] Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, pp. 53-54

[35] Jeremi Suri, “Henry Kissinger and the American Century”, Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 80

[36] Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, p. 55

[37] Walter Isaacson, “Kissinger: a biography”, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1992, p. 55

[38] Charles Stuart Kennedy, Interview with Mr. H. Sonnenfeldt, “The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project”, 2000

[39] https://www.bergstraesser-anzeiger.de/orte/bensheim_artikel,-bensheim-raetsel-geloest-das-haus-ist-gefunden-_arid,461162.html

[40] Jeremi Suri, “Henry Kissinger and the American Century”, Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 81

[41] https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/vonbraun/bio.html

[42] Jeremi Suri, “Henry Kissinger and the American Century”, Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 81

[43] [43] https://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rg-330-defense-secretary ; https://www.archives.gov/files/iwg/declassified-records/rg-330-defense-secretary/foreign-scientist-case-files.pdf

[44] https://ahrp.org/pivotal-role-of-allen-dulles-in-shielding-nazi-war-criminals/

[45] Peter Dale Scott, “Why No One Could Find Mengele: Allen Dulles and the German SS”, The Threepenny Review, No. 23 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 16-18

[46] https://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rg-263-cia-records/rg-263-report.html

[47] https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/hitlers-spione-an-der-ostfront-100.html

[48] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/cold-war-spies-general-reinhard-gehlen/

[49] Paolo Fusi, Il cassiere di Saddam, Consumedia, Bellinzona 2003

[50] https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/the-bizarre-case-of-youssef-nada-and-switzerland-s-role-in-the–war-on-terror-/47075022 ; https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=10ddacd5-8060-407e-b647-39a248d00716

[51] Kenneth J. Campbell, “Otto Skorzeny: The Most Dangerous Man in Europe”, American Intelligence Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2012), pp. 146-147

[52] Peter Dale Scott, “Why No One Could Find Mengele: Allen Dulles and the German SS”, The Threepenny Review, No. 23 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 16-18 ;

[53] https://islandora.wrlc.org/islandora/object/terror%3Aroot

[54] http://rochester.indymedia.org/node/1403

[55] Peter Dale Scott, “Why No One Could Find Mengele: Allen Dulles and the German SS”, The Threepenny Review, No. 23 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 16-18 ; Kenneth J. Campbell, “Otto Skorzeny: The Most Dangerous Man in Europe”, American Intelligence Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2012), pp. 146-147

[56] https://www.antifainfoblatt.de/artikel/lateinamerika-fluchtpunkt-nach-ns-terror

[57] http://www.irwish.de/PDF/Dienste+Kriege/Wertz-Die_Weltbeherrscher.pdf

[58] https://www.antifainfoblatt.de/artikel/lateinamerika-fluchtpunkt-nach-ns-terror

[59] https://www.antifainfoblatt.de/artikel/lateinamerika-fluchtpunkt-nach-ns-terror

[60] https://www.memoiresdeguerre.com/article-terror-s-legacy-schacht-skorzeny-allen-dulles-112826449.html ; http://jens-kroeger.homepage.t-online.de/page1/vatikan.html ; https://www.newsweek.pl/historia/krwawe-miliardy-reichsfurera-ss-czy-himmler-gromadzil-fundusze-na-budowe-iv-rzeszy/nkh2jjb

[61] https://conversacionsobrehistoria.info/2018/12/01/historia-de-un-neonazi-aleman-y-su-fortin-de-alicante/

[62] https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ein-mehr-als-bedrueckendes-schauspiel-a-e0b3da9e-0002-0001-0000-000040763997

[63] http://leg13.camera.it/_dati/leg13/lavori/doc/xxiii/064v01t02_RS/00000011.pdf

[64] https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/stuart-christie-stefano-delle-chiaie

[65] https://www.parlamento.it/773?shadow_organo=405513 ; https://www.derechos.org/sorin/doc/p2.html ; https://archive.org/details/nazilegacyklausb00link

[66] https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/nazi-officer-became-assassin-israel-2-x.html?firefox=1

[67] Marvin and Bernard Kalb, “Kissinger”, Little, Brown, Toronto, 1974, p. 44