Kismayo, the heart of Jubaland (southern Somalia), is a strategic port. Hodan Nalayeh, a BBC Somali Canadian journalist, lives there, back to her roots, her people. Kismayo and Jubaland are among the safest areas in Somalia since Ahmed Mohamed Islaam Madobe, who was already in charge of the Union of Islamic Courts in 2006, became governor in 2013[1]. Madobe has been working hard to expel from the region one of the most feared terrorist organisations on the entire African continent[2]: the Ḥarakat al-Shabāb al-Mujāhidīnal[3], known simply as al-Shabaab. The group was driven out of the region in September 2012, defeated by a coalition led by AMISOM (African Union Mission in Somalia) in collaboration with the regular Somali army[4].

Madobe succeeded in restoring a semblance of tranquillity to a country battered by war and famine; the jihad seemed to have disappeared, and with it the terror. The population is cooperating actively, submitting to very frequent controls[5]. It is in this atmosphere that on Friday 12 July 2019, late in the evening, many guests of the prestigious Asasey Hotel in Kismayo are having a drink at tables in the courtyard, until a terrible explosion destroys the closed gate of the main entrance. The guests flee: four armed men enter the hotel and carry out a massacre, which lasts 14 hours and ends with the elimination of the assailants, who kill 26 people, many of whom are foreigners, including Hodan Nalayeh herself, slaughtered with her husband, the first Somali woman in the world to be the owner of a newspaper[6]. The signal is clear and strong: Al-Shabaab is back, again bringing terror to Kismayo and Jubaland, as already in all Somalia (and not only).

The years of the Islamic Courts

Sheikh Ali Dheere, the pioneer of the Islamic Courts in Mogadishu

Al Shabaab was born in 2006: at that time, the Islamic Courts, which appeared in the first half of the 1990s as a response to the power vacuum created by the implosion of Siad Barre’s regime in 1991[7], dominated a substantial slice of the south of the country. Their sphere of influence was initially limited to the territory of Mogadishu: Sheikh Ali Dheere established the first Islamic Court in the capital in 1993[8], followed by others after successes against rampant crime. The courts, officially independent of each other, are part of the same movement and act particularly in the north of the city. The courts that, since 1996, have sprung up in the southern part of Mogadishu, are strongly influenced by former members of the terrorist organisation Al Ittihad Al Islamiya (AIAI)[9]: this is a group linked to al-Qaeda, based in Ogaden, situated in the south-east of Ethiopia. It was in these areas that AIAI carried out most of its attacks, before being defeated by the Ethiopian army; the dissolution of AIAI led some of its leaders to join the Islamic Courts[10].

Hassan Dahir Aweys, who will become one of the leaders of the council of the Union of the Islamic Courts and, subsequently, spiritual leader of al-Shabaab, founds an Islamic Court in the port city of Merca (70 km south-west of Mogadishu); this court emerges as a platform of Jihadist Islamism, having Aweys, by virtue of his past in AIAI, contacts with several young Somalis trained in Afghanistan[11]. One of these, Aden Hashi ‘Ayro, is involved in the murder of four aid workers, a British journalist and a Somali peacekeeper. The militia Ayro heads is known as Al-Shabaab[12].

The favour they find with the population is due to their ability to ensure the maintenance of order and the operation of essential public facilities such as schools and hospitals: The areas under their control, which after 2000 extend beyond the capital, enjoy a far better reputation than those governed by the warlords[13] who, after the fall of Barre, started the civil war: the United Somali Congress (USC), which leads the fight against Barre, establishes an interim government with Ali Mahdi Mohammed, which triggers splits among the various rebel groups[14]. Among these, the Habr Abgal clan of General Mohammed Farah Aidid emerges and takes control of the southern part of Mogadishu, while the northern part is under the control of Ali Mahdi Mohammed[15].

This is the beginning of the war: in March 1992 the capital has lost 300,000 people, who have died of hunger or disease, while the number of deaths directly related to the fighting is around 44,000[16]. The first UNOSOM humanitarian mission intervened to oversee the truce negotiated by the United Nations between Mahdi Mohammed and Farah Aidid, as well as to create humanitarian corridors useful for the distribution of aid; the mission, which ended in December of the same year, failed in both objectives[17]. The failure is due to the strategy of the UNO: the cycle of talks “Conference on National Reconciliation in Somalia” (UNITAF, Addis Ababa, 1993)[18], has the great demerit of having legitimized the warlords present (representing the 15 factions in conflict), considering them the only ones able to stop the hostilities, to the detriment of the clan leaders and politicians, also present at the conferences[19].

UNITAF and UNOSOM are also a source of enormous enrichment for the warlords. In the Mogadishu area they control the production of most goods and services: here officials and employees of the UN and international NGOs rent houses, hire cars (often armoured and with bodyguards), pay duties on shipments, on the planes that transport them – and sign contracts with local companies. Most of the services purchased by UN officials are in the area controlled by Mohammed Farah Aidid, officially their enemy[20]. The more money the warlords earn, the more they recruit soldiers, strengthen ties with clans (through bribery or threats), pay patronage – all to achieve a militarily hegemonic position[21].

UNOSOM 2 troops in Mogadishu in 1995[22]

The power of the Warlords wanes after the withdrawal of the UNOSOM 2 mission in March 1995[23]. Their reduced financial resources generate a constant loss of soldiers, whose services are bought by members of Mogadishu’s new entrepreneurial class in order to create private militias[24]; from this new class comes support for certain Islamic groups that organise themselves to create islands of security, also carrying out functions of government, in the capital and surrounding areas: the Islamic Courts[25].

The Courts originate as part of the clan power in Mogadishu; they serve some specific sub-clans belonging to the Hawiye clan (of nomadic origin, it is, together with the Darood clan, the largest and most powerful in Somalia[26]) and are supported by the Hawiye middle class of the capital. After the first successes in the north of the city, the Courts begin to be opposed by Ali Mahdi (of the Abgaal sub-clan, belonging to Hawiye), who orders their dismantling[27]; in the south, the experiment of the Courts is not carried out until 1996, given the hard opposition of Ali Mahdi’s rival, General Mohammed Farah Aidid (of the Habr Gedir sub-clan, also belonging to Hawiye), proud enemy of Islamism[28].

In that year, Aidid dies, leaving the way clear for the creation, in 1998, of the first Islamic court in South Mogadishu by the Saleban (Habr Gedir)[29]. The following year two other Habr Gedir clans, Ayr and Duduble, founded their own courts; unlike those in the north, they are linked to Islamic fundamentalism because of the presence of former members of the AIAI[30]. Hassan Dahir Aweys (former colonel in the Somali army fighting in the Ogaden war of 1977[31]) is involved in the creation of the Ifka Halane Court[32]. In 2000, several Islamic courts in the south of the capital ‘consort’, giving rise to the Islamic Court Council, of which Aweys became lord, leaving Hassan Mohmmed Addeh, head of the Ifka Halane Court, as the official leader of the council; the clans, by uniting their militias, are the first group not controlled by the warlords to have a substantial armed force[33].

According to the scholar Robrecht Deforche, Somalia has a tradition of divisions that cannot be erased by nationalism. The unilinear and patriarchal structure of the clans has always been a divisive element, prevailing over unifying elements, such as belonging to the same ethnic and linguistic group or the common religious faith[34]. Since the early post-independence period, corruption and nepotism have been a trademark of clan interference in Somali politics; after the fall of Siad Barre, conflicts exploded with unprecedented violence, instigated by the power vacuum: society gathered around the clan to which it belonged, thus contributing to triggering the spiral of violence that led to the devastation of the country[35].

The creation of a common substratum, a key element in a process of pacification of the country, is attempted with the creation of federal governments – immediately delegitimised; thus, religious affiliation (the Courts) is exploited to respond not only to the power vacuum, but also to corruption and internal divisions between the clans[36]. So, the Courts prosper: in 2003, Sharif Sheikh Ahmed restarts the creation of Islamic Courts in the north of Mogadishu, dismantled in 1996 by Ali Mahdi, and at the end of 2004, all the Courts are united under the name of the Union of Islamic Courts[37], of which Sharif Sheikh Ahmed is the leader[38].

The role of al-Qaeda

The Paradise Hotel blown up in Mombasa by Al Qaeda in November 2002[39]

At the end of 2002, the CIA (the operation is headed by John Bennett, a veteran of the agency, future leader of the National Clandestine Service) initiates a series of contacts with the warlords still active in Mogadishu and other strategic cities, giving them considerable sums of money in exchange for the capture of the Jihadists hiding in Somalia[40]. The CIA believes that, protected by AIAI, the Comorian, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, the Sudanese, Abu Talha al-Sudani and the Kenyan, Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, may find refuge in the country: the three names are linked to the 1998 attacks on the United States embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam[41].

Fazul Mohammed is believed to be the mastermind of those attacks, and despite US efforts to capture him, he remained free until his death at a Somali Transitional Federal Government soldiers’ checkpoint on the evening of 8 June 2011, following a firefight with the military[42]. At the time of his killing, Fazul Mohammed was considered the leader of al-Qaeda in East Africa[43], a position he had achieved through his organisational skills: in addition to the 1998 attacks, he planned the Mombasa attacks of 28 November 2002[44], when the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel was blown up, killing ten Kenyans and three Israelis[45]. At the same time, two SA-97 missiles were fired at a Boeing 757 owned by the Israeli company Akria shortly after take-off from Mombasa airport, but missed the target[46].

No less important is his ability to raise funds for the organisation: concealed by some 40 false identities[47], facilitated by the fact that he speaks five languages[48], and with a face remodelled by plastic surgery[49], Fazul Mohammed is the key to al-Qaeda’s entry into the blood diamonds business, which allows al-Qaeda’s economic survival when the United States blocks other funding for the organisation[50]. From 1999 to 2001, Fazul Mohammed is active in Liberia and Sierra Leone, where he manages not only to launder twenty million dollars, but also to ensure that al-Qaeda has strong ties with important diamond traffickers[51]. He is a key man for al-Shabaab: as the person responsible for the recruitment of foreign fighters and volunteer militiamen, he is the link with the jihadist universe outside of Somalia[52].

In July, 2021, former members of Amniyat (the intelligence of al-Shabaab) reveal that 85% of the capital used to open the International Bank of Somalia (IBS) is owned by Fazul Mohammed[53]. Zakariya Ismail Hersi, former leader of Amniyat and now member of the Somali Intelligence, reveals the existence of relations between Fazul and Mohamed Ali Warsame, owner of IBS: al Qaeda, through Fazul, sends foodstuffs and building materials to Somali entrepreneurs, who sell the goods received and return part of the proceeds[54]. When Fazul is killed, his assets are invested in local companies: according to Hersi, Warsame came into possession of that money (157 million dollars), with which he opened IBS[55].

Abu Talha al-Sudani is an explosives’ expert close to Osama bin Laden: his expertise proved useful to al-Qaeda in both the 1998 attacks and the 2002 attack on the Paradise Hotel in Mombasa[56]. After collaborating with AIAI, al-Sudani puts his experience at the service of al-Shabaab in the fight of the Union of Islamic Courts against the TFG and the Ethiopian Army in 2006[57]. He died in January 2007, killed during an aerial bombardment carried out by the Ethiopian Army along the Somali-Kenyan border[58].

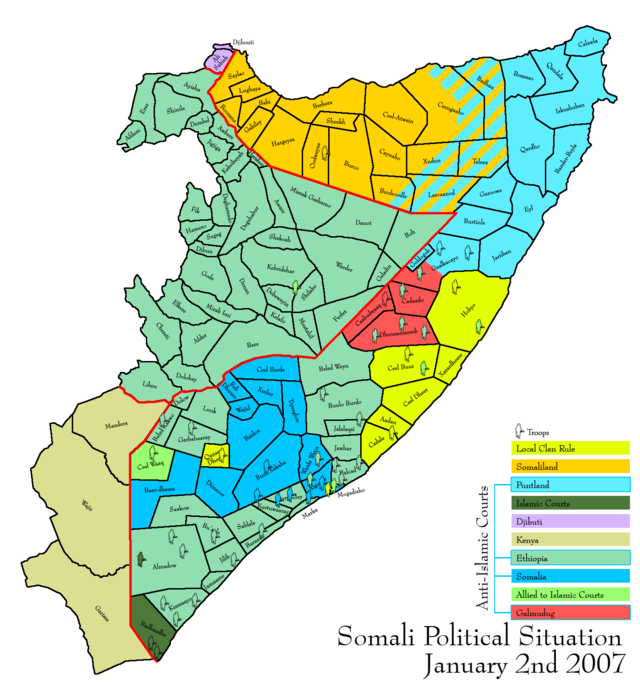

Political and military zones of influence in Somalia in January 2007[59]

The confirmation of al-Sudani’s death is given in an audio message recorded by one of the leaders of al-Shabaab, linked to the militias of the Islamic Courts since 2002 and a prominent member of al-Qaeda in East Africa: Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan[60]. His name is also linked to the attacks in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998 and those in Mombasa in 2002 (it is believed that the vehicle used in the attack on the Paradise Hotel belonged to him[61]). The role of Nabhan as commander of the foreign fighters trained by al-Qaeda in al-Shabaab, during the transformation of the group from militia of the Courts to autonomous terrorist organization, is very important: he is the head of the foreign soldiers, who after 2007, are trained by instructors coming from Afghanistan, as well as by Nabhan himself, in the network of al-Shabaab training camps in central and southern Somalia[62]. Nahban dies on 14 September 2009 near the town of Barawe, south of Mogadishu, under fire from US special forces helicopters[63].

Ibrahim Haji Jama Me’aad is one of the most important figures in the al-Shabaab affair: he arrived in Somalia in January, 1990, after nine years of economic studies at the University of the District of Columbia in Washington, where, to support himself, he worked as an ice-cream vendor, waiter and taxi driver[64]. Most of his time, however, Ibrahim spent at the Islamic Center, one of the largest and oldest mosques in the eastern United States, learning more about Islam – and meeting the man who would change his destiny forever: Abdullah Azzam. Azzam[65], a Palestinian, is considered the first theorist and founder of al-Qaeda[66].

In the mid-1980s, Azzam, with the financial support of a wealthy Saudi by the name of Osama bin Laden, set up a series of lodgings and training camps for aspiring Islamists along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, to which young Muslims inspired by Azzam’s revolutionary pan-Islamist ideas flock. The objective is to drive out the Soviet invader[67]. Azzam (not opposed by the Western governments because he is an enemy of the Soviet Union) holds a series of meetings and conferences in the Middle East, Europe and North America; during a visit to Washington, he meets Ibrahim Me’aad and recruits him[68].

When his student visa expires, Me’aad accepts Azzam’s invitation to leave the US for Peshawar, an important Pakistani city on the border with Afghanistan. Here Me’aad spends a year of training, getting into the good graces of Azzam himself and of the future head of al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri[69]. Abdullah Azzam dies, together with his two sons, in a bomb attack in Peshawar on the 24th November, 1989[70]; a few weeks later, Ibrahim Me’aad, whose name is now Ibrahim al-Afghani, returns to Somalia and distributes a series of video tapes narrating the exploits of the Mujahedin against the Soviet Army from Afghanistan[71]. In February 1991, after the fall of Siad Barre, al-Afghani sets up a training camp in the town of Kismayo, which becomes not only the first jihadist centre in Somali history, but also a place where intelligence techniques and military tactics are taught[72]. Encouraged by the steady influx of volunteers, al-Afghani and his comrades open other camps in southern and central Somalia, most of which are attended by AIAI members[73].

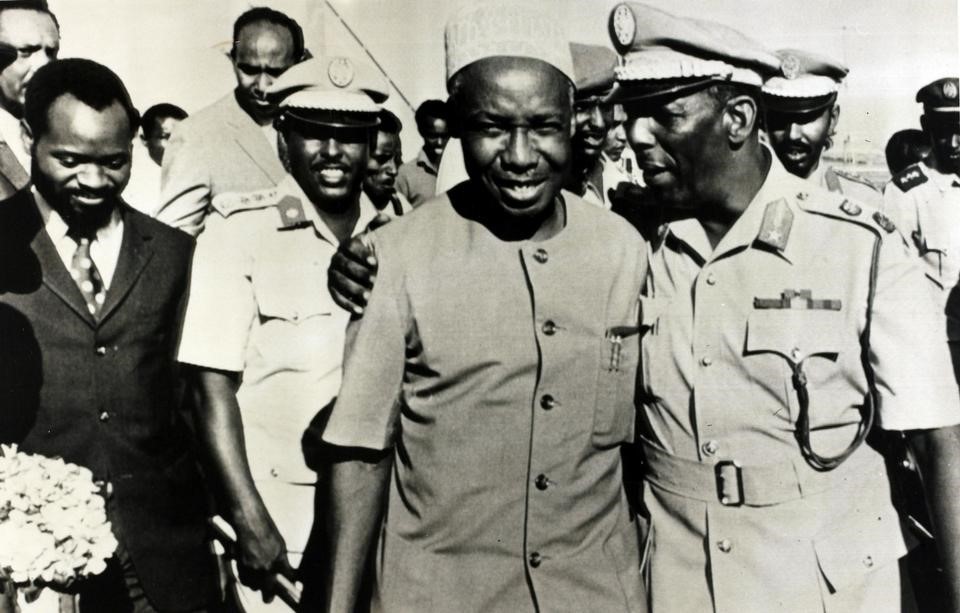

Siad Barre, dictator of Somalia from 1969 to 1991, embraces one of his ministers[74]

At the end of the 80’s, the Salaphite organization (created in 1984) works to create an Islamic State in Somalia, and the peaceful methods give way to the organization of an armed resistance: Ali Warsame introduces the already mentioned Hassan Dahir Aweys into the group, who becomes the head of the growing military wing[75]. At the beginning of the 90’s, AIAI concentrates its efforts against Ethiopia, allying itself with the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), so that in 1996, the Ethiopian Army penetrates Somalia and dismantles the AIAI strongholds, annihilating the organization[76]. The survivors first join the Islamic Courts and, subsequently, al-Shabaab[77].

The leaders of al-Shabaab understand that it is not possible to survive without the support of a part of the population. So where al-Shabaab arrives, stability arrives, violent crime ends, schools reopen, and this contributes, over the years, to a general distrust of successive federal governments. These are generally seen as emanations of foreign interests, established without popular consent and therefore lacking in credibility. Al-Shabaab, on the other hand, does not forget to establish relations with the clans, using them as a means to widen its own base of consensus. Furthermore, the group carries out attacks at home against government or military targets, reinforcing its image as the defender of the Somali people against the “infidels” supported by Ethiopia, Kenya and Western powers[78]. When al-Shabaab acts outside its national borders, however, it shows a very different face.

The failure of AMISOM

Somali fighters under the flags of Al Qaeda (2009)[79]

In Kampala, the capital of Uganda, on 11 July 2010 the Kyadondo Rugby Club is overflowing with people who have come to watch (thanks to a huge TV screen) the World Cup final between Holland and Spain being played in South Africa. Three minutes before the end of the match an explosion blows up dozens of plastic chairs occupied by the patrons. A few seconds later, another detonation, a few metres away from the first one, overwhelmed those present: two kamikazes, hiding among the spectators, blew themselves up[80]. During the interval of the match, in another area of the city, an Ethiopian restaurant is the object of another bomb attack. The number of dead is 74[81]. The claim of al-Shabaab for the attack is tied to the massive presence of Ugandan troops in Somali territory, in the ambit of the already mentioned AMISOM, the peacekeeping mission of the African Union in Somalia[82].

The UN mission called AMISOM was created in 2007 to support the weak Transitional Federal Government and fight its fiercest opponent, al-Shabaab[83]. In addition to Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya are involved in the operation; Sierra Leone joined the mission from 2013 to 2014[84]. In addition to the contributions of military troops, Kenya and Uganda, together with Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Zambia also provide forces with policing tasks[85]. Still active today, AMISOM came into action when the TFG (Federal Transitional Government), after the break-up of the Union of Islamic Courts in December 2006, was only able to resist thanks to the Ethiopian army[86].

In the months following the arrival of government representatives in Mogadishu, the city was again shaken by a series of terrorist attacks, attributable to al-Shabaab, clan militias and warlords who had escaped the disastrous defeat of a few months earlier[87]. Frustrated by the prolonged nature of these attacks, the Ethiopian military reacts with actions of unprecedented violence, bombing entire districts of the capital[88]. The United States, meanwhile, cannonaded Islamist targets in several areas in the south of the country[89]. The atrocities perpetrated by both sides lead to further tragic consequences: the desperate flight of civilians (to Kenya, Ethiopia, Yemen, the United States and Great Britain), a further humanitarian emergency, and an increase in the phenomenon of piracy, which until 2008 was fairly limited[90].

When, in January 2009, Ethiopia withdrew from Somali territory, the former members of the Islamic Courts were divided into three factions: al-Shabaab, Hizbul Islam (the Islamic Party) and the moderate group led by Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, former leader of the Union[91]. Sheikh Ahmed became president of Somalia that same month[92], after the Djibouti Accords of August 2008 sanctioned the agreement between the TFG and the Alliance for the Re-Liberation of Somalia (ARS), the party founded by Ahmed, whereby the parties pledged to cease hostilities, accept UN supervision of their actions, and cooperate in the political, economic and social development of the country[93].

Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, not recognising the authority of the TFG and threatened by the presence of AMISOM troops, formed an alliance[94]. Hizbul Islam is a group created in February 2009 from the fusion of four groups: the ARS – in contrast to the path of dialogue undertaken by its former member, Sheikh Ahmed -, the Ras Kamboni Brigade, Jabhatul Islamiya and Muaskar Anole[95]. The leadership is assumed by Hassan Dahir Aweys, who returned specifically from Eritrea, where he had taken refuge at the time of the ICU defeat[96]. In July, al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam control a large part of central-southern Somalia, but there are very strong tensions between the allies, tied, above all, to the different positions on Osama bin Laden[97].

The Godane era: authoritarianism and internal disagreements

Ahmed Abdi Godane

The growing disagreements between the two groups (in particular, between Aweys and Ahmed Abdi Godane, who in May, 2008, became the new leader of al-Shabaab in place of Aden Hashi ‘Ayro, killed during a United States air attack[98]) lead to military conflict: the spark ignites in Kismayo in September, when a contingent from Ras Kamboni, led by Ahmed Mohamed Islam, better known as Ahmed Madobe, challenges al-Shabaab for control of the city. JABISO and ARS decide not to support their ally, Anole declares himself neutral. Even within Ras Kamboni, Madobe is opposed by another brigade leader: Hassan Abdullah Hersi al-Turki[99].

In October, al-Shabaab expels Madobe’s faction, while al-Turki declares the annexation of his group to al-Shabaab. The episode highlights an objective of the organisation: to remove the danger that the political dynamics linked to the clans could interfere with its decisions, strategies and actions[100]. On the 23rd December, 2010, at a press conference attended by some al-Shabaab leaders, Aweys declares the confluence of Hizbul Islam into al-Shabaab itself[101].

The differences between Godane and Aweys himself, however, do not diminish, fed also by the first serious internal dissensions within al-Shabaab. Certain important members contest, in primis, the authoritarianism with which Godane guides the organization. The tensions explode in a split, which sees the separation of Godane (at the head of a faction composed, to a large extent, of foreign fighters) and Aweys, Mukhtar Robow and al-Afghani (at the head of a nationalist militia)[102].

Godane reacts by declaring a global jihad with al-Shabaab at the side of al-Qaeda (in the hope of increasing the number of foreign fighters); he introduces the use of suicide bombers, figures unknown until then in Somali territory, changes the name of the group to Harakat al Shabaab al-Mujahidin (Mujahidin Youth Movement), and forbids the use of the Somali flag, also “favouring” the marriage between Somali women and foreign militiamen[103]. The nationalists, for their part, reject any kind of alliance with al-Qaeda, the involvement of foreign fighters and the practice of killing apostate Muslims to purify Islam: it is fratricidal war[104].

On 5 July 2010, the IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on Development) approved the deployment of a further 2,000 soldiers from the AMISOM mission and proposed to the UN Security Council that the contingent be increased to 20,000[105]. The opposing factions in al-Shabaab unite against the common enemy: one week after the IGAD meeting, the attacks in Kampala take place[106]. The first great attack of the group outside of Somalia has, as reported, the objective of pushing the Ugandan Government to withdraw its contingent from the mission[107].

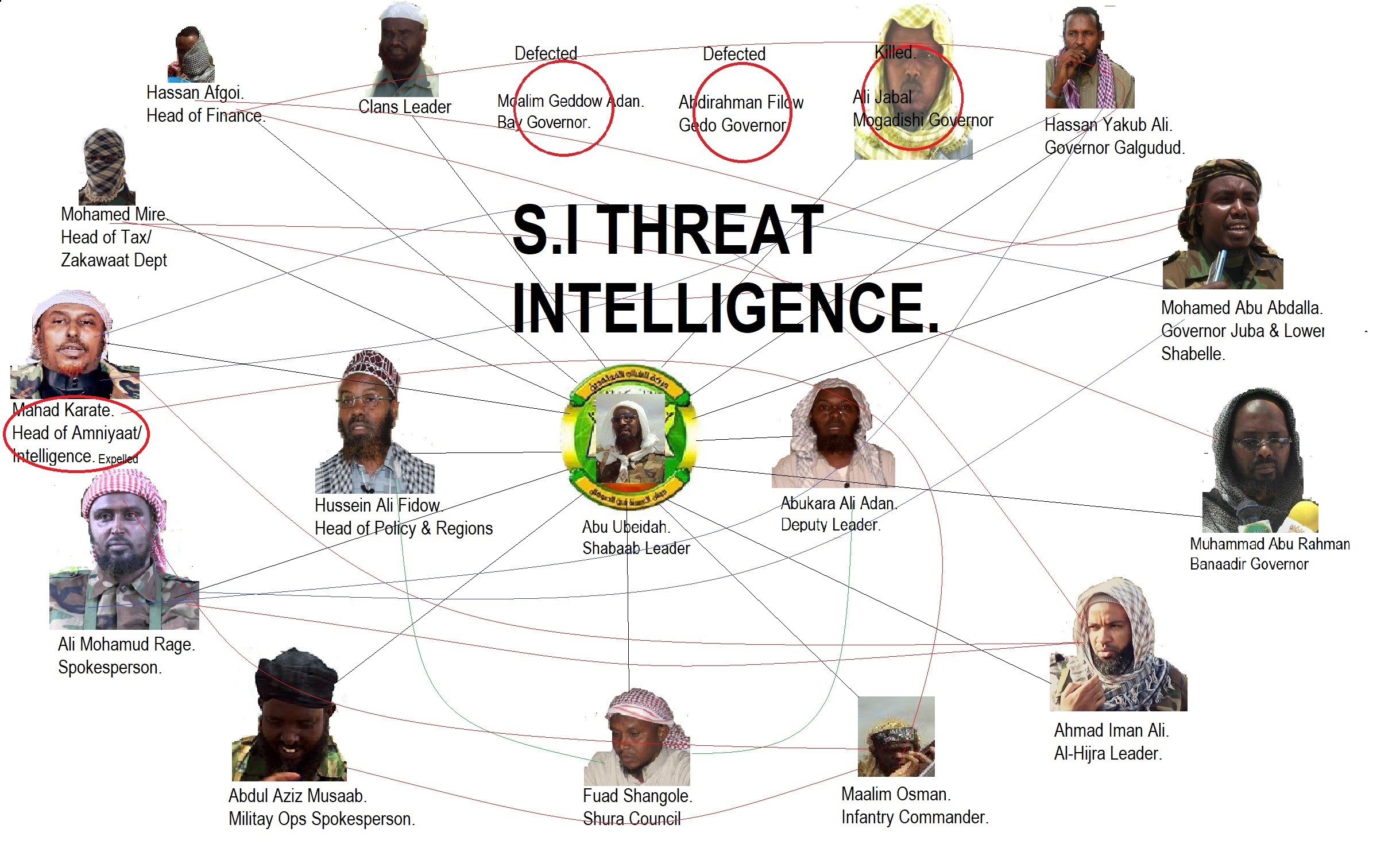

The internal situation of the group, however, remains full of tensions: the same annexation of Hizbul Islam (which is realized on the 23rd December) is the object of dispute between Godane, contrary, and the faction of al-Afghani and Mukhtar Robow, in favour. The moment of weakness resulted in the loss of Mogadishu, conquered by AMISOM in August 2011[108]. Two weeks later, Godane replaces Robow and al-Afghani with Mahad Warsame Qaley Karate[109], alias Mahad Karate[110], who plays a key role in Amniyat, the group’s operational intelligence department[111], and suspends meetings of the Shura, the council of leaders[112]. In February 2012, al-Zawahiri officially declared al-Shabaab’s affiliation with al-Qaeda[113]. The decision to ban UN agencies working to support the population, opposed by Robow and motivated by the possible infiltration of Western spies, causes a worsening of the famine, which kills about 260,000 Somalis, and popular resentment towards al-Shabaab[114].

Kenya: from Operation Linda Nchi to entry into AMISOM

Somali volunteers pray before a fight with Kenyan KDF soldiers[115]

The situation is aggravated by Kenya’s military intervention: Linda Nchi (“protect the nation”) is the name of the operation unilaterally declared on 14 October 2011 and begun two days later, on the 16th[116]: it is the most important Kenyan military operation since independence was achieved, the first in which it sends troops outside national territory. The reasons for this sudden action are obvious: to put an end to the attacks by Somali terrorists or those resident in Somalia[117], but also to put a stop to the immigration of those fleeing Somalia at war: in 2011 almost half a million refugees were registered, most of them hosted in Dabaab[118], which contributes to the growth of anti-Somali sentiment in Kenyans[119].

The KDF troops’ intervention was accelerated by a series of kidnappings and murders involving Western tourists[120], the latest of which was the kidnapping, attributed to al-Shabaab, of two Spanish Médecins Sans Frontières workers at the Dabaab refugee camp on 13 October: the two women, Montserrat Serra and Blanca Thiebaut, were released in July 2013[121]. When Operation Linda Nchi began on 16 October, it also took the Somali transitional government by surprise, as it did not declare its support for the operation until 21 October[122].

The Kenyan government’s decisions in terms of international politics turned out to be a serious own goal, such as Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s decision to meet his Israeli counterpart Bibi Netanyahu to coordinate the two countries in the fight against terrorism[123]; al-Shabaab seized the opportunity: an agreement between the two countries would be preparatory to the destruction of Muslims[124]. All this fuels negative feelings in the Muslim world about the KDF’s intervention.

The objective of the Linda Nchi operation is to liberate the South of Somalia from the control of al-Shabaab; to this end, the Kenyan Army is working with various Somali groups, among which, besides the TFG troops, it is necessary to cite the Ras Kamboni Movement, created by Ahmed Madobe after the split, at the end of 2009, within the Ras Kamboni Brigade: he declares war on al-Shabaab to regain control of Kismayo[125]. It is likely that the Nairobi government has been working for years to create an autonomous region in Jubaland, and is now promising Madobe a future leadership role in the area[126].

The beginnings of the war are difficult due to the unpreparedness of the Kenyan contingent and the strenuous resistance of al-Shabaab, which strikes everywhere, as in Mogadishu during the meeting between the Minister of Defence, Mohammed Yusuf Haji, and the Kenyan Foreign Minister, Moses Wetangula[127]. KDF troops are being hit on a daily basis, while murders of tourists, government officials and police officers continue on Kenyan territory[128]. The response of the AMISOM troops and their allies in the ENDF (Ethiopia National Defence Forces)[129] forced al-Shabaab to withdraw in order to avoid a confrontation on three fronts.

In June 2012, the KDF is integrated into the AMISOM contingent[130]. On September 28, 2012, al-Shabaab militias leave Kismayo following a joint attack by Kenyan and Somali military forces[131], with the support of Ras Kamboni Movement militias[132]. The Linda Nchi operation is officially over, but the Kenyan presence in Somalia is destined to last for a long time, not without consequences; al-Shabaab, despite an objective weakening and the loss of key territories, still controls most of Southern Somalia and is determined to reorganize itself, evolving as needed.

The showdown

Mukhtar Robow, left, with Omar Hammami, known as Abu Mansoor al Amriki, in Mogadishu in 2011[133]

This means, first of all, resolving internal issues: on 20 June 2013, Godane’s militias kill two members of the opposing faction, including al-Afghani[134]. Mukhtar Robow remains in hiding until August 2017, when he turns himself in to the Somali authorities[135]: a result of the political strategy of national reconciliation with the nationalist members of al-Shabaab supported by President Farmajo, with the backing of the Trump government, which on 23 June excludes Robow, through the Treasury Department, from the wanted list[136].

After coming out of the closet, Robow declares himself opposed to al-Shabaab’s positions and invites its members to leave the group[137]. On 13 December, he is arrested in Baidoa by the Ethiopian contingent of AMISOM, in an action supported by the federal executive, with the ill-concealed intention of excluding him from the race; the manoeuvre causes serious disturbances in an area where al-Shabaab maintains its presence[138]. He is placed under house arrest in Mogadishu, where he remains[139]. Hassan Dahir Aweys also escapes, but is arrested on 26 June 2013 in Himan and Heeb, an autonomous region in central Somalia[140]. Like Robow, he was transferred to Mogadishu and placed under house arrest, where he remains[141].

Godane continues with the elimination of members suspected of having supported the losing leaders, such as the American, Omar Shafik Hammami, known as Abu Mansoor al-Amriki[142], a central figure in the renewal of al-Shabaab since October, 2007, known for his numerous propaganda videos, filmed in real-tv style during military actions, or commented in rap style by Hammami – all videos which register tens of thousands of views on YouTube, and contribute to motivate potential foreign fighters, also from the United States[143]. Godane’s purge reinforces al-Shabaab’s image as a force linked to the international jihadist movement, but reduces its military capacity, as the majority of the militia come from Mukhtar Robow’s Rahanweyn clan; the elimination of foreign fighters close to Robow and Aweys curbs the arrival of potential new recruits from abroad[144].

In addition to isolated attempts to regain lost territories through military campaigns, the group alternates an increasing number of terrorist actions, which highlight al-Shabaab’s ability to strike anywhere at home and abroad: on October 4, 2011, a truck bomb explodes in Mogadishu near the headquarters of the Central Investigation Department, killing 100 people, mostly students waiting to take a scholarship exam in Turkey[145]. On 8 November 2014, an al-Shabaab contingent conquers Kudhaa Island, 130 km southwest of Kismayo, taking it from the control of Interim Juba Administration (IJA) forces, who had taken it only two weeks earlier. Forty-three IJA soldiers and thirty-one al-Shabaab militiamen died in the battle[146]. Two actions with very strong propaganda results.

Abroad, al-Shabaab aims to kill as many civilians as possible: on the one side, it strikes countries that support AMISOM, on the other, it obtains the attention of the world and renders credible the effective importance of the group in the al Qaeda galaxy. This was achieved with the attack on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi on 21 September 2013: four members of the group, wearing masks, entered the luxury shopping centre, killing everyone they met and barricading themselves inside the building. The siege by the Kenyan armed forces does not end until 24 September. Sixty-seven people died, in addition to the four attackers, more than two hundred were injured[147]. A resounding success.

A woman who escaped the massacre at the Westgate Mall in Nairobi on 21 September 2013[148]

In their 2020 paper, (“Al-Shabaab. Anatomy of the Terrorist Organisation that Abducted Silvia Romano”), Brendon J. Cannon and Dominic Ruto Pkalya identify eight reasons for al-Shabaab’s ferocity in Kenya:

- a) Geographical proximity: Kenya borders the part of Somali territory that remains under al-Shabaab’s control; this allows the organisation to carry out numerous actions in the border area, such as Mandera (2016[149]) and Garissa (2015[150]), in addition to attacks against foreigners along the coast[151];

- b) Visibility: Kenya (especially thanks to mass tourism) is one of the most important states in sub-Saharan Africa. Nairobi hosts numerous embassies, a United Nations headquarters and that of many international NGOs (including Africa Milele Onlus, for which Silvia Romano, kidnapped on 20 November 2018, works[152]);

- c) Media coverage: the Kenyan Constitution guarantees the media the highest degree of freedom and autonomy from state power. This condition, uncommon in the region, favours the presence of numerous independent national and foreign media outlets (CCTV, CNC World, BBC and Al-Jazeera)[153];

- d) Tourism: the objective of forcing Kenya to withdraw its troops from the AMISOM contingent is favoured by the large presence of foreign tourists[154];

- e) The recruitment of Kenyan foreign fighters: Kenya supplies al-Shabaab with a number of fighters far superior to other nations, constituted of Moslems opposed to the Western presence in the area[155];

- f) The ease of setting up terrorist cells in Kenya, which derives from what has been described. Worthy of note, in this regard, is the al-Hijra organisation, considered the emanation of al-Shabaab in Kenya[156];

- g) Authoritarianism vs Democracy: Striking a democratic country like Kenya, where the population has the power to influence politics, is an ideological advantage for a large part of the population of the Islamic faith[157];

- h) Corruption: this phenomenon is endemic in Kenya. This causes a condition of general unpreparedness and inadequacy on the part of the State to deal with a well-trained and prepared group such as al-Shabaab[158].

The Westgate Mall attack was followed a few months later by other incursions in Kenya: on 23 March 2014, al-Shabaab members broke into a church in the town of Likoni, near Mombasa, killing four people and wounding 17[159]. Nairobi is hit on 1[160] and 23 April[161]. From April 2, as part of the anti-terrorist operation “Usalama Watch”, the police carry out indiscriminate raids and arrests (650) in the Eastleigh district of Nairobi, called “Little Mogadishu”, and in other areas with a strong Somali population, encouraging jihadist propaganda[162].

The huge cage in which Kenyan police detained those arrested in the Usalama Watch operation on 2 April 2014[163]

In this regard, the murder in Mombasa on April 1, 2014 of Abubaker Shariff Ahmed, known as Makaburi, a religious leader identified by the United Nations as a recruiter of young Muslims for al-Shabaab[164], caused quite a stir. Two years earlier, in August 2012, another religious leader in Mombasa, Aboud Rogo Mohammed, also accused of being a supporter of al-Shabaab, was killed in the street[165]. In October 2013, Ibrahim “Rogo” Omar, Aboud Rogo Mohammed’s successor, was shot dead in his car[166]. The consequence of these Kenyan police killings[167] is the massacre that took place on 15 June 2014 in the coastal village of Mpeketoni, during which an al-Shabaab commando killed around 50 inhabitants in three hours[168].

The internal structure of al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab pirates just apprehended by French Navy[169]

In 2014, AMISOM had more than 22,000 soldiers in Somalia[170], and the leader of Al-Shabaab, Ahmed Abdi Godane, killed in a US air strike on 1 September 2014, is the most famous victim of the international military commitment[171]. This is the death of the man who transformed the militia into a rigid and efficient pyramid structure, which Harun Maruf and Dan Joseph were able to reconstruct thanks to direct interviews with former members of the organisation, giving an account of it in the book “Inside Al-Shabaab – The Secret History of Al-Qaeda’s Most Powerful Ally”.

At the head of al-Shabaab are the Shura (advisory body, composed of 38/40 members) and the Tanfid (with decision-making power, composed of the most influential members of the clans, militias and religious). The decisions of the Tanfid are communicated to the maktabs (a sort of governmental agencies), the number of which is variable, but which certainly include: Da’wa (preaching), Zakat (taxation), Wilayat (regional administration), Amniyat (security), Jabhat (army), Garsoor (judgement and justice), plus others of minor importance. The leaders of the maktabs are replaced frequently, to prevent them from gaining too much power[172].

A central role is played by the maktab Da’wa, set up to maintain the leaders’ conception of Islam: it reforms mosques, libraries and other public institutions, rejecting all references to Sufism and taking the lead in organising religious functions and the school system – schools are used as a vehicle for indoctrination, and the Bay and Bakool regions, where al-Shabaab has schools and training camps, provide the largest number of affiliates[173].

Women must wear the hijab or burqa, men’s hair must not exceed a certain length, it is forbidden to smoke, watch films, listen to western music and chew khat (a drug widespread in Somalia). These and other regulations are enforced by Hisbah, the al-Shabaab police, whose members are dressed in uniforms and equipped like many other corps performing similar functions. The crimes are judged by the Garsoor, the judicial body, generally without giving the accused the possibility of defending themselves[174].

The structure of religious, civil and military control requires a huge and continuous outlay of money; in this regard, the role of the maktab Zakat is fundamental. In every region under the control of al-Shabaab, the rulers (waali) use Zakat to administer the taxation system; taxes are levied on every economic activity, the proceeds of which are largely used to finance military operations. The largest revenues come from excise duties on truck transit (the price to be paid is up to 1,200 dollars per vehicle, for a single passage) and from payments in livestock received by the owners of large herds and pastures; the animals are resold in the markets, generating high profits[175].

The Amniyat, al-Shabaab’s security and espionage body[176]

Al-Shabaab also receives substantial revenue from its relationship with Somali piracy, a phenomenon generated by the discontent of Puntland fishermen with the ruthless competition of foreign fishing boats, which become the object of systematic attacks, with the crews taken hostage and released after payment of a ransom[177]. Between 2005 and 2011, around 1100 attacks took place, of which more than 200 were successful[178]. A number of factors have contributed to the decline in pirate activity since 2013, including the presence of private security guards on the ships and the massive presence of international naval forces in the area[179], as well as the conquest by AMISOM troops of several strategic ports previously held by al-Shabaab, effectively reducing the possibility of safe harbours for hijackers[180].

Between 2008 and 2010, the pirates negotiated with al-Shabaab to gain access to ports controlled by the organisation, which in return received part of the ransom proceeds (between 100,000 and 200,000 dollars per operation)[181]. Between 2005 and 2012, piracy generated around 400 million dollars[182], laundered through arms and khat trafficking, especially with Kenya[183]. Al-Shabaab, for its part, administers the proceeds of coal exports to Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Iran[184], as well as collecting support from “friendly” countries like Eritrea[185].

What allows al-Shabaab to control the territory is the military apparatus. Aspiring militiamen are sent to training camps, where the teachers are al-Qaeda experts. At the end of the extremely hard training, the new affiliates are divided between the Jabhat and the Amniyat. Jabhat soldiers fight in the field against TFG and AMISOM. The best elements enter the Amniyat, which is responsible for organising suicide attacks and bombings and performs espionage functions[186].

Amniyat is divided into three units: Jugta Ulus, specialized in the use of missiles, bazookas and heavy machine guns; Mukhabarad, which is the espionage unit; the third branch is the Mutafajirad and is specialized in suicide missions[187]. Amniyat is the fulcrum around which the identity, credibility and authority of al-Shabaab as a terrorist group revolves: the scholar, Mohamed Mubarak, besides speaking of the important role of women in this apparatus, affirms that the members of the various units of Amniyat do not know each other and do not know the activities of the others; the faces of all are always covered, so that the identity of each one is known only to his own leader[188].

The members of al-Shabaab know the identity of the new emir less than a week after Godane’s death. On September 6, Ahmed Diriye, better known as Ahmed Omar Abu Ubaidah, was announced; a member of the Dir clan, like his predecessor, Abu Ubaidah has been with al-Shabaab since 2006, and is one of the most influential members of Amniyat[189]. Under his leadership, al-Shabaab continues al-Qaeda’s jihadist campaign[190]. In 2015, however, a new player entered the scene, one that was destined to wreak new havoc in the ranks of the organisation: ISIS.

During the course of the year, al-Qaeda’s rivals published a series of videos online calling on al-Shabaab to fight for Abubakr al Baghdadi. The first to respond is the Puntland group of Abdul Qadir Mumin, considered the head of ISIS in Somalia since 2016[191]. His defection takes on a strong symbolic meaning: Mumin’s exit is a symptom of the dissatisfaction within al-Shabaab with the despotism of Abu Ubaidah[192], an inflexible takfiri warrior like his predecessor[193]. In December 2014, Zakariya Ismail Ahmed Hersi, al-Shabaab’s intelligence chief, surrendered to the Somali government, accusing Abu Ubaidah of excessive ferocity[194].

The terror continues

3 April 2015: al-Shabaab’s terrorists massacre 148 students and professors at Garissa University College[195]

The chain of attacks in Somalia and Kenya continues, with a large number of civilians among the victims (more than 3,000 since 2015)[196]; in 2015, on April 3, a massacre took place at the Garissa University College (Garissa, Kenya), in which 148 people, mostly students, were killed by the attackers after it was ascertained that they were Christians[197]. On 14 October 2017, two truck bombs are detonated in the Hodan District, in the north-west of Mogadishu: at least 587 people die, also due to the explosion of a tanker truck near the vehicle bombs[198].

The United States designated al-Shabaab as a terrorist organisation in 2008: between then and 24 August 2021, 254 attacks were launched on Somali territory (most of them during the Trump presidency), killing 1800 people (including members of ISIS and al-Qaeda), including two emirs: Ayro and Godane[199]. The situation has not changed: al-Shabaab resists the defections and hostility of the people (who had supported it at the time of the Ethiopian invasion in 2006 and until 2008[200]), constantly strikes AMISOM[201] troops and the Somali National Army (SNA)[202], extending its range of action also to the autonomous region of Puntland, in the north-east of the country[203], where the situation becomes more turbulent, also following the appearance of ISIS and the subsequent separation of the Mumin group[204].

After years of weakness and mistrust, the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), which replaced the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in 2012, has made undeniable progress[205]. However, its ability to penetrate the country remains limited, also due to tense relations with regional governments[206], especially with the institutions of Jubaland, which led to a clash between militias loyal to the region’s security minister and the federal army in February 2020[207].

Kismayo is the most important city in Jubaland, due to the number of its inhabitants and the large port built by the United States in 1964[208], which is so precious to those who govern the region, such as al-Shabaab until 2012. Its inhabitants have lived almost in peace ever since. Then comes July 13, 2019, with the attack on the Asasey Hotel[209], as a tremendous warning to all those who hope to return to a normal life: al-Shabaab is less strong, perhaps, but it is alive, present and always very dangerous.

In 2018, the Somali Federal Government and AMISOM sign an agreement for the gradual withdrawal of troops, but it is not known when or if this will happen, because the international contingent is still decisive in the fight against al-Shabaab[210]; the United States completes the withdrawal of its troops from Somalia in January 2021 (they are deployed to other bases in the area[211]), at a time when the situation is seriously unstable, even in Mogadishu[212]. The seizure of power by the Taliban in Afghanistan, celebrated by al-Qaeda[213], could push al-Shabaab to attempt a similar feat in Somalia[214], which without foreign troops could succeed.

The American peace strategy failed: between 2001 and 2011, it made the mistake of launching a military campaign against the only force capable of restoring some stability to Somalia (the Union of Islamic Courts); at that point, the US supported the Ethiopian intervention, the country plunged into chaos, giving legitimacy to al-Shabaab. The next mistake is to support the TFG, suspected of colluding with AIAI: the fact that the US is constantly working alongside Ethiopia, because of Addis Ababa’s hegemonic ambitions and the behaviour of Ethiopian troops in Somalia, brings the government into disrepute, condemning it to perpetual weakness[215].

The proceeds of al-Shabaab

Markets in which al-Shabaab earns a percentage for each transaction[216]

To better understand how al-Shabaab can sustain the amount of investment needed to maintain its structure, plan military and terrorist operations, supply weapons and ammunition, and develop new training camps, it may be useful to provide some data on the group’s income: The UN Security Council’s Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea estimates that it managed to collect between 70 and 100 million dollars a year until 2011[217], largely derived from the export of coal from ports and the taxation imposed on companies transporting the same coal and sugar[218].

With the loss of many strategic ports and the UN ban on Somali coal exports, al-Shabaab reduced its business volume to around $38-56 million per year (trade revenue and taxation on coal ports) in 2014[219], and reacted with the Charcoal Ban, which put coal traders and transporters in danger, imprisoned and militarily attacked[220].

Another obstacle to the group’s coal activity comes from the United Arab Emirates’ ban on illegal coal imports from Somalia, which further reduces coal traffic in 2016[221]. The taxation on imports and exports of sugar increases in relation to the diminishing revenues deriving from coal activities: for each truck that passes through its territories, al-Shabaab receives, in 2016, 1500 dollars (against 1000 in the previous year), rendering the group an estimated profit of between 12 and 18 million dollars per year[222].

The complex system of taxation on commercial activities and individuals, regulated by the Zakat maktab, earned al-Shabaab 90 million dollars in 2011 for the city markets of Mogadishu, Baraka and Suuq Baad alone[223]. In the following years, taxes on agriculture remained an important source of income[224], while since 2016, taxes on local populations have increased, while the quality of services offered to communities has generally decreased[225]. Humanitarian aid organisations also pay a tax to be allowed to operate in regions controlled by al-Shabaab[226], as was also the case during the famine that hit the country in 2011[227].

Various commercial and tourist activities are bribed by the organisation, which “protects” them in exchange for a fixed payment[228]. The remittances of Somali citizens living abroad, one of the main sources of sustenance for a large part of the population, are also subject to the attentions of al-Shabaab, which withholds an unspecified percentage of the billion dollars a year that enter Somali territory[229]. Eritrea supported al-Shabaab with about $50,000 a month from 2006 to 2008[230], before reducing the amount of money it sent in 2012[231]. In 2009, Qatar was also accused of sending funds to the organisation[232].

The growing activity of al-Shabaab in Puntland may have as an objective, in addition to fighting ISIS, to intensify relations with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), a group active mainly in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, and share in its financial profits[233]. Somalia’s largest telephone company, Hormuud Telecom, is believed to be one of al-Shabaab’s largest financiers[234]: the company is also used by the organisation to pay salaries to its affiliates[235]. The ability of the group to use local banking institutions (Salaam Somali Bank) to launder money abroad, especially in the real estate sector, is currently growing[236]. Since 2009, Al Shabaab has had its own communications office, the al-Kataib Media Foundation, which creates and disseminates propaganda material[237].

Turkey’s commitment and prospects for Somalia

Turkish President Erdogan reviews Somali government troops[238]

It is clear that Somalia cannot find peace as long as there is a war between Islamic fundamentalists, Western troops and tribal clans. But the tribal clans alone are unable to agree among themselves and coordinate their efforts to get the nation back on its feet. That is why, so far, there are only three possible allies of the Mogadishu government that can tackle the problem: Russia, China and Turkey. And it is above all this third country that is putting all its strength into annexing Somalia into its sphere of influence.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan set foot on Somali soil in August 2011, when the country experienced a terrible drought, which added to the famine in worsening the disastrous humanitarian situation. As well as contributing to the population’s livelihood by sending humanitarian aid, Turkey launched an infrastructure investment plan[239]. Ankara launched the largest aid campaign in Turkish history, raising USD 300 million, plus a further USD 350 million from members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), which Turkey had called for at an extraordinary assembly it had convened[240]. With this aid, the government sent aid workers, doctors and officials to set up field hospitals and distribute food and medicine to the population – and shortly afterwards Turkish Airlines became the first airline to re-establish air links with Somalia in over 20 years[241].

The Turkish commitment continues with the construction of roads[242], schools[243], hospitals[244] and state institutions, such as the Somali parliament building[245]. Erdogan has used the state-run Maarif Foundation to open schools close to the Muslim Brotherhood in several countries around the world, including Somalia[246]. Many of these schools replaced those opened in previous decades by Fethullah Gülen[247]. Gülen and Erdogan, allies since 2002, came into open conflict after the corruption scandal in Turkey erupted in 2013[248]. Gülen, who has been in exile in the United States since 1999, founded over a hundred schools in Turkey and private education centres in 110 countries around the world through his Hizmet / Ceemat movement[249]. In 2016, the Erdogan government banned Gülen’s movement, renaming it a terrorist group and giving it the name Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation (FETO)[250].

In response to the major effort in the country, in early 2020 the Somali government invites Turkey to proceed with drilling off the Somali coast for oil[251], as part of a 2019 law on exploitation of fields enacted by Mogadishu to attract foreign investment in the exploration phase[252]. The site to be explored covers an area of about 100,000 square kilometres disputed between Kenya and Somalia, which is why the Somali government’s invitation to foreign drilling could sour relations between the two countries[253].

The volume of trade between the two countries is growing, rising from USD 144 million in 2017 to USD 206 million in 2019[254]. In Mogadishu, the Turkish army’s largest military base and academy on foreign soil, called Camp TURKSOM, opened in 2017, where up to 1,000 Somali soldiers are trained at the same time[255]; due to its role in the growth of the Somali armed forces, the base is the target of attacks by al-Shabaab[256].

Since 2013, the Turkish Foreign Ministry has been constantly mediating between the Somali federal government and the Somaliland administration[257]: the United Arab Emirates, in response to the growing Turkish influence in the area, has decided to invest in the strategic port of Berbera, in Somaliland, an important outpost on the Red Sea very close to Yemen[258]. Other rivals of Turkey reacted: the Saudi prince Mohamed Bin Salman declared in 2018 that Turkey was trying to build a new Ottoman caliphate, a sign that relations with the Gulf countries were problematic after the coup in Egypt against President Mohamad Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, thus supported by Erdogan[259]. Relations became more complicated in 2017, when Turkey supported Qatar in the crisis with Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Egypt[260]. The interests of Ankara and Doha converge on Somalia, where in 2020 the two countries embark on a campaign to recruit mercenaries to be used in the Libyan conflict alongside the Government of National Accord[261].

All these steps are a necessary prerequisite for taking the military confrontation to another level, namely the economic one. The moment Berbera Port becomes a real alternative to the Egyptian port of Port Said and China completes the road linking these ports to the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola, there will be a common interest among Muslim countries in ensuring that al-Shabaab becomes just a bad memory, and that the clans have more interesting choices on which to divide. It is a pragmatic solution, of course. Like all those that can really work.

[1] https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2018/06/15/somalie-madobe-le-chef-djihadiste-devenu-frequentable_5315671_3210.html

[2] Jamal Osman, “Somalia: ‘My Bloody Country’” – BBC Africa Eye full documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YH6f0azpOrg

[3] https://www.ilmattino.it/primopiano/esteri/silvia_romano_rapita_terroristi_amniyat-4717847.html?fbclid=IwAR3bKlxG6gqhfB0JMlpfFARPsoyB7fGO1l4UjP0OBPkZ31-5LwDPtNJH6uo

[4] http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/amisom-press-release-30-09-2012.pdf

[5] Jamal Osman, “Somalia: ‘My Bloody Country’” – BBC Africa Eye full documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YH6f0azpOrg

[6] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/somalia-hotel-siege_n_5d29b2f0e4b0bd7d1e1cc673

[7] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 59

[8] https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-courts-union#text_block_19602

[9] https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-courts-union#text_block_19602

[10] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 53

[11] International Crisis Group, “Can the Somali Crisis Be Contained?”, in Africa Report 116 (10 August 2006), pp. 9-10

[12] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 53

[13] https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-courts-union#text_block_19602

[14] https://www.hrw.org/reports/1993/WR93/Afw-08.htm

[15] https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/somalis-bury-aideed-scourge-us-army

[16] Bjørn Møller “The Somali conflict: the role of external actors” DIIS Report 2009:03, pp. 11-12

[17] Mark Bradbury e Sally Healy “A brief story of the Somali conflict”, in Accord, an international review of peace intiatives – Issue 21 – 2010, p. 10

[18] “The United Nations and Somalia 1992-96”, The United Nations Blue Books Series, Volume VIII – Department of Public Information United Nations, New York – 1996, p. 30

[19] Stig J. Hansen “Warlord and Peace Strategies: The Case of Somalia”, in The Journal of Conflict Studies – Fall 2003, pp. 62 e 65

[20] Stig J. Hansen “Warlord and Peace Strategies: The Case of Somalia”, in The Journal of Conflict Studies – Fall 2003, p. 67

[21] Stig J. Hansen “Warlord and Peace Strategies: The Case of Somalia”, in The Journal of Conflict Studies – Fall 2003, p. 67

[22] https://www.wikiwand.com/en/United_Nations_Operation_in_Somalia_II

[23] The United Nations and Somalia 1992-96”, The United Nations Blue Books Series, Volume VIII – Department of Public Information United Nations, New York – 1996, p. 68

[24] Stig J. Hansen “Warlord and Peace Strategies: The Case of Somalia”, in The Journal of Conflict Studies – Fall 2003, p. 66

[25] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 58

[26] Robrecht Deforche, “Stabilization and Common Identity: Reflections on the Islamic Courts and Al-Itihaad”, in Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies – Volume 13 – 2013, p. 108

[27] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p. 152

[28] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p. 152 ; https://rpl.hds.harvard.edu/faq/islamic-courts-union

[29] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p. 152 ; Roland Marchal, “Harakat al-Shabaab al Mujaheddin in Somalia”, CNRS SciencesPo Paris, March 2011, p. 15

[30] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p. 153 ; https://www.egic.info/islamist-contagion-in-somalia

[31] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 22

[32] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p. 153

[33] Cedric Barnes e Harun Hassan, “The Rise and Fall of Mogadishu’s Islamic Courts”, in Journal of Eastern Africa Studies – vol. 1 – July 2007, p.153

[34] Robrecht Deforche, “Stabilization and Common Identity: Reflections on the Islamic Courts and Al-Itihaad”, in Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies – Volume 13 – 2013, p. 109

[35] Robrecht Deforche, “Stabilization and Common Identity: Reflections on the Islamic Courts and Al-Itihaad”, in Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies – Volume 13 – 2013, p. 109

[36] Robrecht Deforche, “Stabilization and Common Identity: Reflections on theIslamic Courts and Al-Itihaad”, in Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies – Volume 13 – 2013, p. 110

[37] Robrecht Deforche, “Stabilization and Common Identity: Reflections on theIslamic Courts and Al-Itihaad”, in Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies – Volume 13 – 2013, p. 113

[38] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 38

[39] https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/israel-interested-in-accepting-guantanamo-bay-terrorist-for-prosecution-474931

[40] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 28-29

[41] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 59

[42] https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/12/world/africa/12somalia.html

[43] https://www.corriere.it/esteri/11_giugno_11/alberizzi-fasul-comoriano-ucciso_3b5096d6-945e-11e0-9db6-651cd37b13cb.shtml

[44] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-110hconres441ih/html/BILLS-110hconres441ih.htm

[45] https://www.timesofisrael.com/us-wants-israel-to-try-gitmo-prisoner-for-2002-kenya-bombing-report/

[46] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-108hres76ih/html/BILLS-108hres76ih.htm

[47] https://www.un.org/press/en/2012/sc10755.doc.htm

[48] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia-alqaeda/somalia-says-killed-top-african-al-qaeda-operative-idUSTRE75A10H20110611

[49] https://www.un.org/press/en/2012/sc10755.doc.htm

[50] https://ctc.usma.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Fazul.pdf

[51] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13738393 ; https://ctc.usma.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Fazul.pdf

[52] https://issafrica.org/iss-today/killing-of-fazul-abdullah-mohammed-in-somalia-a-blow-to-al-shabaab

[53] https://sunatimes.com/articles/6264/85-of-the-capital-of-IBS-Bank-of-Somalia-belongs-to-Al-Shabab

[54] https://sunatimes.com/articles/6264/85-of-the-capital-of-IBS-Bank-of-Somalia-belongs-to-Al-Shabab

[55] https://sunatimes.com/articles/6264/85-of-the-capital-of-IBS-Bank-of-Somalia-belongs-to-Al-Shabab

[56] https://ctc.usma.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Abu_Talha_al.pdf

[57] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 42

[58] https://jamestown.org/brief/briefs-214/

[59] https://www.wikiwand.com/en/2007_in_Somalia

[60] https://jamestown.org/brief/briefs-214/

[61] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8256024.stm

[62] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 89

[63] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia-conflict-idUSLE02100020090915

[64] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 11-14

[65] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 11-14

[66] David H. Shinn “Al-Qaeda in East Africa and the Horn”, in “The Journal of Conflict Studies – Summer 2007”, p. 48

[67] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 11-14

[68] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 11-14

[69] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 15

[70] https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/jcs/article/view/219/377

[71] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 15

[72] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 18-19

[73] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, p. 19

[74] https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/socialist-somalia-the-legacy-of-barre-s-military-regime-30735

[75] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Al Ittihad Al Islamiya.” Stanford University. Last modified February 2019. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/al-ittihad-al-islamiya

[76] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Al Ittihad Al Islamiya.” Stanford University. Last modified February 2019. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/al-ittihad-al-islamiya

[77] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Al Ittihad Al Islamiya.” Stanford University. Last modified February 2019. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/al-ittihad-al-islamiya

[78] Blake Edward Barkley, “Manipulating State Failure: Al-Shabaab’s Consolidation of Power in Somalia”, University of Calgary, September 2015, pp. 21-23

[79] https://www.dw.com/en/somalia-former-al-shabab-militants-share-their-story/a-40848898

[80] https://web.archive.org/web/20100715062221/https://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/956212/-/x22qke/-/ ; http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/africa/07/12/uganda.bombings/?hpt=T1 ; https://web.archive.org/web/20100715054623/http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/12/725545

[81] https://web.archive.org/web/20100715062221/https://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/956212/-/x22qke/-/ ; http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/africa/07/12/uganda.bombings/?hpt=T1 ; https://web.archive.org/web/20100715054623/http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/12/725545

[82] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jul/12/uganda-kampala-bombs-explosions-attacks

[83] “African Politics, African Peace – AMISOM Short Mission Brief”, World Peace Foundation – Tufts University, July 2017, pp.5-6

[84] http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1862623570&Country=Ethiopia&topic=Politics&subtopic_9

[85] https://amisom-au.org/mission-profile/military-component/

[86] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 53-54

[87] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 52-53

[88] Napoleon A. Bamfo, “Ethiopia’s invasion of Somalia in 2006: Motives and lessons learned”, in African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Vol. 4(2), February 2010, pp. 62-63

[89] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-strikes-in-somalia-reportedly-kill-31/ ; https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/blowback-somalia/

[90] Napoleon A. Bamfo, “Ethiopia’s invasion of Somalia in 2006: Motives and lessons learned”, in African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Vol. 4(2), February 2010, p. 63

[91] Mohamed Haji Ingiriis (2018) From Al-Itihaad to Al-Shabaab: how the Ethiopian intervention and the ‘War on Terror’ exacerbated the conflict in Somalia, Third World Quarterly, 39:11, 2033-2052, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2018.1479186

[92] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2009/5/30/profile-sharif-ahmed

[93] https://www.peaceagreements.org/view/825

[94] Mapping Militant Organizations. “Hizbul Islam.” Stanford University. Last modified February 2019. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/hizbul-islam

[95] Aisha Ahmad (2016) Going Global: Islamist Competition in Contemporary Civil Wars, Security Studies, 25:2, 353-384, DOI: 10.1080/09636412.2016.1171971 , p. 367

[96] https://www.ict.org.il/Article/1071/Jihadi%20Arena%20Report%20Somalia%20-%20Development%20of%20Radical%20Islamism%20and%20Current%20Implications#gsc.tab=0

[97] https://www.ict.org.il/Article/1071/Jihadi%20Arena%20Report%20Somalia%20-%20Development%20of%20Radical%20Islamism%20and%20Current%20Implications#gsc.tab=0

[98] https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/02/world/africa/02somalia.html

[99] Aisha Ahmad (2016) Going Global: Islamist Competition in Contemporary Civil Wars, Security Studies, 25:2, 353-384, DOI: 10.1080/09636412.2016.1171971 , p. 369

[100] Aisha Ahmad (2016) Going Global: Islamist Competition in Contemporary Civil Wars, Security Studies, 25:2, 353-384, DOI: 10.1080/09636412.2016.1171971 , p. 369

[101] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/profile-sheikh-hassan-dahir-aweys

[102] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, pp. 212-213

[103] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, pp. 212-213

[104] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, pp. 212-213

[105] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Somalia%205%20July%20IGAD%20communique.pdf

[106] https://www.repubblica.it/esteri/2010/07/12/news/uganda_attentati-5526975/

[107] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, p. 213

[108] https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/140221_Bryden_ReinventionOfAlShabaab_Web.pdf

[109] https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/140221_Bryden_ReinventionOfAlShabaab_Web.pdf

[110] https://www.somtribune.com/2015/04/11/somalia-places-bounty-on-al-shabaab-leaders/

[111] https://web.archive.org/web/20170203085034/https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/other/des/266532.htm

[112] https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/140221_Bryden_ReinventionOfAlShabaab_Web.pdf

[113] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/profile-ahmed-abdi-godane-mukhtar-abu-zubair

[114] https://theglobalobservatory.org/2014/06/is-al-shabaab-resurgent-or-weakening-a-tale-of-two-narratives/

[115] https://www.scoopnest.com/user/KTNKenya/689704307952881664-factors-working-against-kdfs-operation-linda-nchi-in-somalia

[116] Nyagudi Musandu Nyagudi, review of the book “Operation Linda Nchi” – Kenya’s Military Experience in Somalia by KDF/MoD Kenya, January 2015

[117] “The Kenyan Military intervention in Somalia”, International Crisis, Group, Africa Report N°184 – 15 February 2012, p. 1

[118] Vikram Kolmannskog, “Gaps in Geneva, gaps on the ground: case studies of Somalis displaced to Kenya and Egypt during the 2011 drought”, Policy Development and Evaluation Service | UNHCR, Norwegian Refugee Council, December 2012, p. 2

[119] “The Kenyan Military intervention in Somalia”, International Crisis, Group, Africa Report N°184 – 15 February 2012, p. 3

[120] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/04/kenya-kidnap-attacks-tourism-hit

[121] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-23359943

[122] “Communiqué of the 41st Extra-ordinary Session of the IGAD Council of Ministers”, IGAD, Addis Abeba, 21 October 2011

[123] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15725632

[124] https://english.alarabiya.net/articles/2011%2F11%2F16%2F177485

[125] https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/ras-kamboni-movement#_edn7

[126] https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2013/0708/Is-Kenya-birthing-a-new-country-named-Jubaland

[127] https://www.refworld.org/docid/4eaaa819c.html

[128] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, pp. 215-216

[129] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/timeline-operation-linda-nchi#MonthTwo

[130] “Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security Council resolution 2060 (2012): Somalia”, United Nations Security Council, July 2013, p. 27

[131] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-19769058

[132] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/sep/28/kenyan-soldiers-capture-kismayo-somalia

[133] https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/what-robow-s-arrest-means-for-somalia-and-al-shabab-23957

[134] https://edition.cnn.com/2013/06/29/world/africa/somalia-militant-killed/index.html

[135] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/13/world/africa/al-shabab-abu-mansoor-mukhtar-robow-somalia.html

[136] Luca Puddu, “Corno d’Africa e Africa Meridionale”, Osservatorio Strategico 2017 – n. III, p. 43

[137] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia-security/former-senior-al-shabaab-leader-says-militants-should-leave-group-idUSKCN1AV14S

[138] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia-politics-arrest-idUSKBN1OC1D8

[139] https://www.garoweonline.com/en/news/somalia/ex-al-shabaab-deputy-mukhtar-robow-goes-to-hunger-strike-in-mogadishu

[140] http://www.bar-kulan.com/2013/06/26/himan-and-heb-held-a-key-al-shabaab-figure/

[141] https://www.thestar.com/news/world/2017/03/10/my-meeting-with-a-forgotten-terrorist-in-somalia.html

[142] https://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/omar-hammami-american-rapping-jihadist-killed-somalia/story?id=20234254

[143] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 77-80

[144] John Edward Maszka, “A Strategic Analysis of Al Shabaab”, Bournemouth University, February 2017, p. 217

[145] https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_al-shabab-attacks-killed-4000-past-decade-says-data-gathering-group/6182660.html

[146] https://www.voanews.com/a/al-shabab-takes-somali-island/2514466.html

[147] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-29282045

[148] https://www.timesofisrael.com/kenya-hits-somali-al-shabab-camp-after-mall-attack/

[149] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37759749

[150] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/03/world/africa/garissa-university-college-shooting-in-kenya.html

[151] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[152] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2020/05/09/silvia-romano-liberata-cronologia-del-rapimento-dal-sequestro-in-kenya-nel-2018-alla-pista-islamista-di-al-shabaab/5796860/ ; Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[153] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[154] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[155] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[156] https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-01-25/group-behind-nairobi-s-recent-terror-attack-recruits-young-people-many-faiths

[157] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[158] Brendon J. Cannon e Dominic Ruto Pkalya, “Al-Shabaab. Anatomia dell’organizzazione terroristica che ha rapito Silvia Romano”, Rubbettino Editore – 2020, pp. 8-12

[159] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/23/kenyan-church-attack-four-worshippers-dead-gunmen

[160] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26827636

[161] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-27134695

[162] https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article/114/454/1/2195212?login=true

[163] https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/kenyan-somali-somali-in-kenya-kenya-in-somalia-kasaraniconcentrationcamp/

[164] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-islamist-idUSBREA301MN20140401 ; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-24263357

[165] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-19390888

[166] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-24395723

[167] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-islamist-idUSBREA301MN20140401

[168] David M. Anderson, “Why Mpeketoni matters: al-Shabaab and violence in Kenya”, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre, Policy Brief, September 2014, p. 1 https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/183993/cc2dacde481e24ca3ca5eaf60e974ee9.pdf

[169] https://www.france24.com/en/20141204-eu-strasbourg-court-orders-france-pay-somali-pirates-thousands-compensation

[170] https://amisom-au.org/2014/01/ethiopian-troops-formally-join-amisom-peacekeepers-in-somalia/

[171] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-29034409

[172] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-94

[173] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-94

[174] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-94

[175] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-94

[176] https://intelligencebriefs.com/al-shabaabs-amniyat-head-of-operations-in-mogadishu-muse-moallim-muawiye-resigns-nisa-reports/

[177] https://www.france24.com/en/20180511-video-revisited-puntland-somalia-piracy-pirateland-hijacking-coastguards-fishermen-shabaab

[178] https://www.worldbank.org/en/events/2017/01/26/pirates-of-somalia-crime-and-deterrence-on-the-high-seas#1

[179] http://www.safeseas.net/the-decline-of-somali-piracy-towards-long-term-solutions/

[180] http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/300/Why+piracy+in+Somalia+has+declined

[181] “The Pirates of Somalia – Ending the Threat, Rebuilding a Nation”, The World Bank | Regional Vice-Presidency for Africa, 2013, p. 74 https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/182671468307148284/pdf/76713-REPLACEMENT-pirates-of-somalia-pub-11-2-15.pdf

[182] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/publication/pirate-trails-tracking-the-illicit-financial-flows-from-piracy-off-the-horn-of-africa

[183] https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2013/November/pirate-trails-tracks-dirty-money-resulting-from-piracy-off-the-horn-of-africa.html

[184] UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, Letter dated 2 October 2018, p. 6

[185] https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-eritrea-somalia-un-idUKBRE86F0AI20120716

[186] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-91

[187] Harun Maruf e Dan Joseph, “Inside Al-Shabaab”, Indiana University Press – 2018, pp. 84-91

[188] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48390166?fbclid=IwAR0jdrRAJKBWAyiee9QDGJJXmpvZMFJGmRIOmpB6wexDSPscUs2a5g9nd-U

[189] https://www.counterextremism.com/extremists/ahmed-umar-abu-ubaidah

[190] https://rewardsforjustice.net/english/abu_ubaidah.html

[191] https://www.repubblica.it/esteri/2018/11/21/news/lo_scontro_tra_al_shabaab_e_isis-somalia_per_l_egemonia_della_jihad_nel_corno_d_africa-212219571/