Among the many secret stories of united Italy, there is one that never seems to end: that of the Banco Ambrosiano, which was the crossroads of the interests of the Holy See, Freemasonry, the DC, the Mafia and Opus Dei. It never ends, because the Ambrosiano’s money has never been found: the moment Sindona and Calvi began to have problems with the judiciary, the organisations that had drained the bank’s coffers began to hide the loot, and to do so they used not one, but a dozen networks of financial companies hidden in tax havens. They thought they were cunning, powerful and immortal – and they all ended miserably, dead to the world.

The secret history of Banco Ambrosiano is therefore a story of trustees: bankers and lawyers who, in their consultancy firms, made as much money (and debts) disappear as they could, and as fast as they could. The result is that, in the chaos that ensued, multimillionaire sums disappeared or were used by those who were not entitled to do so, and this is probably the reason for the many settlements of accounts, which ended in deaths, and which continued until the beginning of this century: twenty years, between the Calvi murder and the latest infighting, in which those who had hidden the money tried to keep it (or used it to give themselves a dream), and those who were looking for it took no prisoners.

The most important story that has emerged over the years is that of the Ticino trustee Helios Jermini – a man no one knew anything about until the day he bought a provincial football team (FC Lugano), showered it with champions, and took it all the way to eliminating Inter from the UEFA Cup. A man who paid for this with his life, drowning in Lake Lugano, in circumstances never really clarified, in the spring of 2002. Since then, the suspicious deaths have ended, but the story continues. To understand it, one has to go back to its beginnings, almost 150 years ago…

The “Rome capitol” works scandal

Between 1901 and 1906: workers of the Società Generale Immobiliare Roma demolished the old villas on the Palatine Hill to replace them with new roads and administrative buildings[1]

The relationship of interdependence between Freemasonry and the Italian State arose with the process of the unification of the country, partly as a result of diplomatic relations between lodges of different orientations present in the Vatican State, the Kingdom of Savoy, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Austrian possessions[2]. In 1859, the Grand Orient of Italy (GOI) was founded in Turin, which became the lodge that coordinated all Masonic lodges in the Kingdom. Or rather: it was reborn, because during the years of Napoleonic rule, Freemasonry, throughout Europe, was the symbol of the struggle against absolute monarchies[3], so much so that, in 1814, even Victor Emmanuel I of Savoy banned the formation of lodges[4].

The GOI was born even before the Albertine Statute (the Savoy constitution) became the fundamental law from the Alps to Sicily[5], and obtained royal approval thanks to the negotiation between the Freemason Giuseppe Garibaldi and the King, on October 28, 1860, during the meeting of Teano[6]: Garibaldi, having conquered the South, was threateningly going back to Rome, and Victor Emmanuel II, who wanted the Red Shirts to recognise the authority of the Turin monarchy[7]. The Hero of the Two Worlds accepted for reasons that were anything but noble: at Teano, the King granted privileges to Garibaldini and Freemasonry, recognising their role in the construction of the new Italy, but above all he promised Garibaldi and his sons Menotti and Ricciotti a seat in Parliament and a slice of the juicy contracts for the construction of the Kingdom’s public buildings[8].

The first effect of this negotiation was the transformation of the Banca dello Stato Pontificio into the Banca Romana – no longer a national bank but nonetheless still authorised to mint money. Having obtained permission from the monarchy to finance the construction of the public buildings, Termini Station and Via Nazionale, the Bank founded the Società Generale Immobiliare Roma (1 September 1862) and financed it by printing money outside the agreements with the central bank, creating a gigantic bubble of real but worthless money, used to pay for land, materials and labour[9].

In May 1880, Ricciotti Garibaldi and other Freemasons obtained most of the contracts and financing from the Banca Romana, and were then swept away by the bankruptcy of the bank, which also dragged with it the bankruptcy of the Società Generale Immobiliare Roma and all the other major Italian banks, which had invested in both the Banca Romana and the venture for Roma Capitale[10] – a huge scandal that ended in a sealed deal: on 22 September 1887 the monarchy ‘lends’ the money to pay for the hole (to be repaid, interest-free, in one hundred years), the Banca Romana is liquidated and resurrected as the Banco di Roma, with a 25% shareholding of the Vatican[11] (which condemns membership of the lodges with excommunication[12] ) and the Società Generale Immobiliare Roma is refinanced. All the defendants were acquitted[13].

Rome flourished in the years when the Mayor was the republican Ernesto Nathan (Grand Master of the GOI)[14], the Red Shirts were in opposition in the socialist ranks, and the monarchists paid the price for the scandals to rebuild the city[15]. At the head of the Banco di Roma, with the support of the other minority shareholder banks, the Holy See placed Ernesto Pacelli, cousin of Pope Pius X[16], at the helm. Pacelli, with a view to opposing the progressive secularisation of the state[17], promoted international agreements with the nascent Muslim Brotherhood and[18], after many hesitations, accepted the birth of a confessional party opposing on the one hand the monarchists and liberals (loyal to the king) and on the other the republicans and socialists (working for democracy)[19].

Ernesto Nathan, Republican, Jew and Freemason (Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy), the best Mayor in the history of Rome[20]

The Banco di Roma, at a time when the Popular Party was standing for the first time in the elections (in 1919, it would take over 20% of the vote – a totally unexpected success), was once again in great difficulty, and Pius X agreed that the ABSS (Amministrazione dei Beni della Santa Sede, until 1967 the Vatican’s financial holding company[21]) should sell its share to pay off the debts incurred in the previous twenty years[22]. Instead of the Pope’s most trusted men, the most influential men of the Popular Party, such as Giuseppe Vicentini[23] and Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi[24], entered the board of directors. They enter, because they represent the new majority shareholder: Credito Nazionale, which is the bank that, from day one, finances the political activities of the Popular Party[25].

These are the same men who, twenty years later, would negotiate the Lateran Pacts between Benito Mussolini and the Vatican – negotiations simplified by the increasingly desperate situation of the Banco di Roma and the Credito Nazionale, which would lead many leaders of the PPI (and the Holy See[26]) to join fascism[27]. Chapters 20 and 24 of the Lateran Pacts should be understood in this context, prefiguring the Vatican’s political and diplomatic neutrality and the immunity enjoyed by its representatives abroad – a measure that would allow Fascism to partly circumvent international economic sanctions and use the Holy See to procure food and raw materials in defiance of the embargo[28].

The certainly most famous case: that of the SASEA (Société Anonyme Suisse d’Exploitations Agricoles) SA Geneva, founded by the Vatican in 1883 to secure strategic supplies after the end of the Papal State, and which over the years has set up more than 300 trading companies around the world[29]. A group of companies that played a fundamental role during the 20-year fascist period, especially during the blockades organised by the Allies during the Second World War. A group that was sold to the financier Florio Fiorini, which led to a $377 million bankruptcy in 1991[30].

The role of Giulio Andreotti

May 1960: the President of the Organising Committee of the Rome Olympic Games Giulio Andreotti (left) and Mayor Umberto Tupini (right)[31]

Once the war was over, the Società Generale Immobiliare obtained billions in contracts for reconstruction work[32]: following the merger between Credito Nazionale and Banco di Roma, it became one of the largest banks in Italy, the largest financer of the new Catholic party[33] (the Christian Democrats, also financed by the Marshall Plan in an anti-communist key[34]). The Americans poured billions of dollars[35]into the Società Generale Immobiliare (General Real Estate Company) for the reconstruction work in Rome in preparation for the Holy Year of 1950[36]: roads, railways, hotels, the Fiumicino airport, the restoration of monuments, museums and public buildings – but also for similar work in Milan, Turin and other major Italian cities[37].

This was followed by the major building projects for the 1960[38] Rome Olympics. A project for which Italy and the United States again poured billions[39], almost entirely contracted out to the Società Generale Immobiliare, which spent more than twice as much as planned and, in this way, also financed the current DC of Giulio Andreotti (president of the Games Organising Committee) and the notorious mayors Salvatore Rebecchini and Umberto Tupini[40] – the ones who handed the city over to the developers[41]. The cost overrun was so great that it led to a result that no one would have expected: in 1962 the Società Generale Immobiliare was practically bankrupt, and the IOR, which held control of it, together with the Bank of Rome, did not have the money to cover the deficit[42].

It would only be discovered decades later that most of the missing money had transited through the offshore accounts of a Swiss bank controlled by the Banco Ambrosiano: the Banca del Gottardo, founded in Lugano in 1957[43] and secretly controlled through a Liechtenstein company, the Lovelok Establishment Vaduz[44]. The Pope reacted by hiring the Sicilian financier Michele Sindona as a consultant, who in his reform of the IOR convinced the Holy See to sell its share in the Società Generale Immobiliare to BPI Banca Privata Italiana, newly founded by Sindona, and in which the IOR held 24.5% – at zero price, in exchange for the assumption of the Vatican’s debts by BPI[45].

The BPI founded a series of offshore companies to secretly transfer both the ownership and the debts of the Società Generale Immobiliare as far away from the Vatican as possible. These companies are administered by trust companies founded by the Banca del Gottardo and directed, for the most part, by two young accountants: Pietro Brocchi and Helios Jermini, in a total (at least apparent) confusion between what belongs to Sindona, what belongs to Calvi and the Ambrosiano, and what belongs to the IOR.

An example: Sindona’s company Compendium SAH Luxembourg (which years later changes its name to Banco Ambrosiano Holdings SAH Luxembourg[46]), in 1971, buys from the IOR, for 52 million dollars, 50% of the Banca Cattolica del Veneto, but assigns the shares to Banco Ambrosiano (which, in fact, in the future, turns out to be the owner[47]), and then transfers the shares to an offshore company administered by the Banca del Gottardo[48], the Radowal Financial Establishment Vaduz[49], which places them in an account opened at the IOR[50]. That money is not on any Ambrosiano balance sheet, so the 52 million dollars was paid by someone else, and the Ambrosiano is not the real owner of the 50%, but only the trustee.

Summer 1953: two old friends meet, Pope Pius XII and Giulio Andreotti[51]

And in fact those shares, after a long tour around the world, return to the availability of the IOR, but certainly no longer have to appear on its balance sheet. Just as well, because those shares are full of debts[52], which are transferred to UTC United Trading Company Inc. Panama, based at the Banca del Gottardo[53]. An immense and intentional confusion. As for Compendium, this is founded by Lovelok, but is then sold to Etablissement pour Participations Internationales Eschen (Liechtenstein), whose board members include Pietro Brocchi and Helios Jermini[54].

Sindona did not perform this service by chance: the son of a Sicilian florist, he made his money with the Black Stock Exchange and the Mafia (and the support of the American and British secret services) after the Allied landings in Sicily, and continued to work for these secret services after the war[55]. When the American press, years later, began investigating his takeover of the Franklin Bank, the journalist following the trail of mafia-secret service links, Jack Begon, was kidnapped for 28 days and, when he was freed, remembered nothing except the fact that Sindona flew, like Andreotti, in Henry Kissinger’s private plane[56].

They put enough fear into him to convince him not to write any more: David Matthew Kennedy, the president of the Continental Illinois Bank[57], was also involved in the takeover of the Franklin Bank. Kennedy, together with Kissinger, was to be a minister during the Nixon presidency[58]. The two, great friends, are among the President’s closest men[59], and together they head the Commission on International Trade and Investment Policy, which manages the policy of financial support for politicians and political movements abroad[60].

When he arrives in Rome, Sindona is still a nobody: a young and ambitious Sicilian gangster who has earned the trust of the Allies. The person who called him, Pope Paul VI, before he became Pope was the private secretary of Pope Pius XII, i.e. the cousin of the president of the Banco di Roma, Eugenio Pacelli. Sindona worked for a few months at that bank, then moved to APSA, under the direction of Cardinal Amleto Cicognani. This man, for almost thirty years Vatican Ambassador in Washington, is a very powerful man, and is the mentor of the Bishop of Chicago, Paul Marcinkus[61], who becomes a great financial and political ally of Sindona. But the man pushing to bring Sindona to Rome is another: he is the powerful Giulio Andreotti, who considers him ‘a genius’[62].

Sindona then works in the Società Generale Immobiliare, and finally, on 12 December 1968, he is surprisingly appointed administrator of the Holy See’s assets – on the day when the one-party government led by Giovanni Leone (in which Andreotti was Minister of Industry) falls and a new government led by Mariano Rumor is voted in, exactly one year before the Piazza Fontana massacre in Milan[63]. P2 member Adolfo Sarti became Under-Secretary for Finance[64], while Andreotti, touched by the SIFAR scandal[65], had to step aside: he had been ordered to destroy the illegal archive built by the military secret service (SIFAR), which was organising a coup d’état – but before setting the papers on fire, he allegedly gave a copy to Licio Gelli[66].

David Matthew Kennedy, the man at the centre of relations between Michele Sindona, Henry Kissinger, Giulio Andreotti and US President Richard Nixon[67]

That 12 December 1968 is considered, by some historians, as the caesura between post-war Italy, monopolised by the DC, and the beginning of the strategy of tension, wanted by the Americans after Rumor installed the first centre-left government and fear grew in Washington that, sooner or later, the Communist Party (which soundly beat the unified Socialists in the May national elections[68]) might come to power. The date of the first great fascist massacre would be chosen for its symbolic value[69].

In any case, Sindona has the right connections: Roberto Calvi, Chicago Cardinal Paul Marcinkus, and the Ticino financier Tito Tettamanti who[70], in Vaduz, founds the first company – the one from which all Sindona’s business and banking operations will spring: Fasco AG[71]. This company participates in a whirlwind of money transfers (often fictitious transactions) that serve to conceal the true owners of various assets that, in reality, belong to the Holy See, but must be hidden for two reasons: either they are burdened with heavy debts of unconfessable origin, or they are assets that, under the new Italian tax laws, introduced in June 1968 by the monocoloured Leone government, would oblige the Vatican to pay billions in taxes[72].

The Banca del Gottardo galaxy

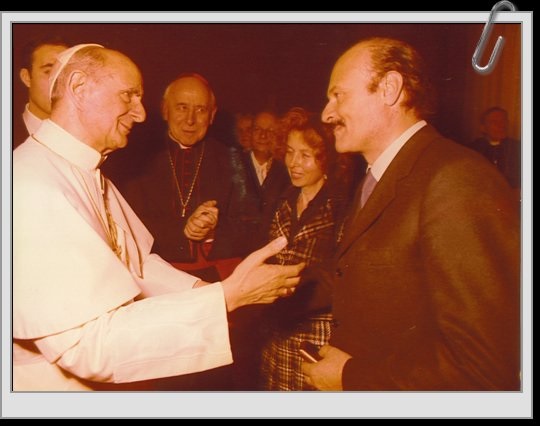

Pope Paul VI receives Roberto Calvi and his wife, Clara Canetti[73]

In December 1968, Banco Ambrosiano and Banca del Gottardo found themselves at the centre of an unstoppable whirlwind of money (or presumed money) arriving from the IOR[74] or from dozens of other inexplicable sources and redistributed in Lugano to a myriad of companies[75], most of them registered in tax havens. The preferred system is that of “portage”[76] and “patronage”[77]: the IOR signs a contract for a series of transactions with the Banca del Gottardo and the bank, in turn, signs a contract with one of its employees who, from that moment on, communicates directly with the IOR, which is able to transfer money without the control (and without any official trace in the balance sheets) of the Banca del Gottardo – and if the IOR requests it, it does so with the formula of patronage, which is a surety without any guarantee[78].

This is the formula by which the Banco Ambrosiano collapses, because it is bound by a series of contracts that oblige it to pay sums in the name of the Holy See which, it is known from the outset, will never be returned. When, exceptionally, the sums are returned to the base, no one knows for sure to whom they are to be paid, because the IOR has concealed the origin of the financial transaction and, therefore, has not disclosed the eventual ultimate beneficiary[79].

The person in charge of operations at the Banca del Gottardo is Angelo De Bernardi[80] , who channels the IOR’s money (or the letters of patronage claiming that the money exists) to the United Trading Corporation SA Panama and redistributes it, in the form of a credit guaranteed by the Luxembourg holding company of Banco Ambrosiano, to a galaxy of Liechtenstein companies[81] and to Zitropo Holding SA Luxembourg, from where the money leaves for a new tour of the planet[82].

As has been said, many of these transactions pass through the Banca del Gottardo, but the most mysterious (and there are dozens of them for billions of lire) are carried out by Finimtrust SA Luxembourg – a trust company of the Belgian bank Kredietbank which, for contracts with the IOR, has set up a special company, Manic Holding SA Luxembourg, of which Angelo De Bernardi is a board member[83], which in turn fills the pockets of dozens of offshore companies[84], so much so that colossal sums are definitively lost. A large part of that money was used by Opus Dei to finance the Banco Espirito Santo in Lisbon[85] – a bank closely linked to Salazar’s dictatorship[86] and Opus Dei’s leadership in Portugal[87].

Tracing all the sums is so difficult because the Banco del Gottardo set up trust companies for some of its employees. The most famous of these is Ultrafin AG in Zurich (branches in Lugano and Vaduz[88]), on whose board of directors Roberto Calvi and his most loyal Ticino collaborators, Fernando Garzoni and Francesco Bolgiani, passed[89]. After the scandal broke out, the company was sold to BSI Banca della Svizzera Italiana[90] , which at the time was controlled by Tito Tettamanti [91], and which had already unveiled the Bremo Establishment Triesen (Liechtenstein), managing to evade judicial investigations[92].

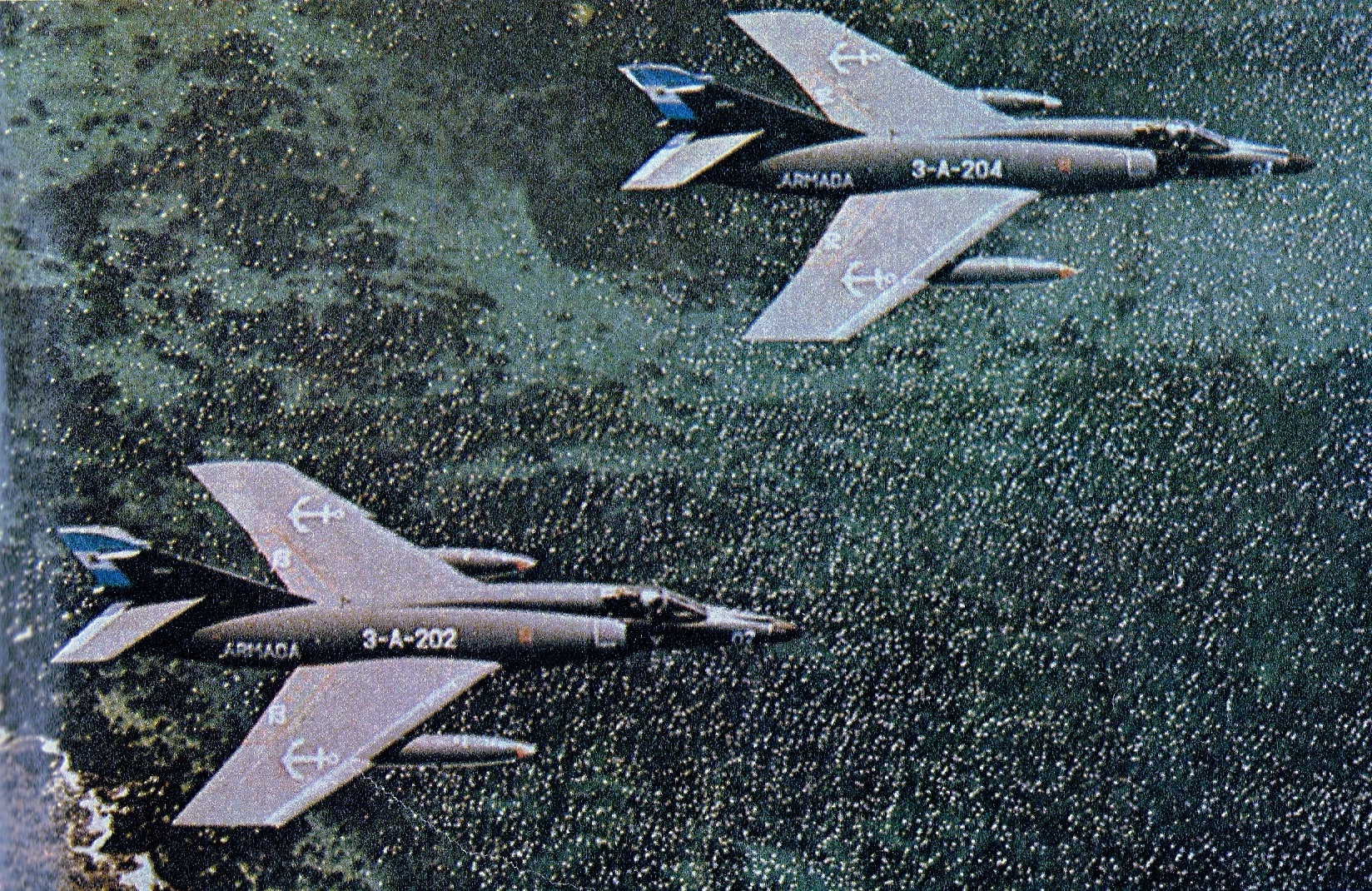

April 1982: Argentine fighter jets, armed with Exocet missiles, paid for by the IOR and Opus Dei through the offshore corporate structure of the Banca del Gottardo, fly over the skies of the Falkland Islands[93]

The money that the IOR passed through this company served, among other things, thanks to Licio Gelli’s mediation, to arm Argentina with French Exocet missiles for the war in the Falklands: Ultrafin paid them to its Peruvian subsidiary, Banco Ambrosiano Andino SA Lima, which in turn paid them to Central American Services SA San José (Costa Rica), owned by the head of Peru’s Opus Dei, Dionisio Romero, who in turn paid the missiles to France in the name and on behalf of the Argentine dictatorship[94].

Gesfid, on the other hand, is the vehicle through which two young managers of the Banca del Gottardo, Pietro Brocchi and Helios Jermini, opened a still largely unknown series of companies, whose money then took very surprising routes. One example: on 2 February 1973, the very young palazzinaro (and member of the P2 Lodge[95]) Silvio Berlusconi founded Italcantieri, which was to build Milan 2, the district with which Berlusconi would achieve wealth, and which was to be built with a cable TV system that would later be the start of Telemilano, the channel from which the entire Fininvest television empire would be born[96].

Italcantieri is administered by Berlusconi, but the money is someone else’s: it comes from Cofigen SA Luxembourg (50%)[97] and Eti SA Chiasso (50%). Eti SA Chiasso pays its share in trust, in the name and on behalf of Aurelius Financing Company Ltd. Chiasso[98]. The latter is controlled by the Interchange Bank, founded by the dairy industrialist Remo Cademartori, a collaborator of the American secret services and for this reason engaged in a last desperate attempt to avoid the lynching of Mussolini, to hand him over to the Allies[99].

The money from the bank, with which Cademartori dreams of building a city of happiness in Venezuela[100], disappeared into the Aurelius and other trust vehicles – all under the portage system: the Interchange Bank, because of the contracts signed by its employees, is responsible for the unsecured loans granted to other companies[101]. The directors of Eti and Aurelius are Ercole Doninelli and his wife Stefania Doninelli Binaghi[102] – two members of the board of directors of FiMo SA in Chiasso, which launders money from South American drug cartels in Switzerland[103]. To clarify: this part of the money given to Berlusconi has a very opaque, and far from encouraging, origin.

The other half of the money comes from Cofigen AG Chiasso, which belongs to the BSI Banca della Svizzera Italiana (which at that time is controlled by Tito Tettamanti[104] ) and COFI Compagnie de l’Occident pour la Finance et l’industrie[105] , a Luxembourg company of the PKB Privatkredit Bank in Zurich[106] – a small private bank, founded by an offshore company of the BSI of Luxembourg which, after the bankruptcy of Banca del Gottardo, buys Gesfid (renames it Banca Gesfid, cleansed from top to bottom and then liquidated[107]), and then, while keeping its offices in Zurich, moves the bank’s headquarters to Nassau (Bahamas)[108].

The bank is given to an employee, Umberto Trabaldo Togna[109]. One who, among other things, through PKB buys and closes Banca Rasini (which in the meantime has repeatedly changed hands[110] – the one suspected of links with the Mafia that had financed Silvio Berlusconi’s first steps in the building trade[111]. As if to say that the two groups that dominate in Ticino, the Fidinam of Tito Tettamanti and Giangiorgio Spiess (who is one of Licio Gelli’s lawyers[112]) on the one hand, the Banca del Gottardo of the IOR and the Banco Ambrosiano on the other, have financed Berlusconi as part of the reorganisation of the IOR’s illegal holdings and the offshore companies they created to move the dozens of portages made in the name of the Holy See, Opus Dei, the Mafia or who knows who else.

The star of Helios Jermini is born

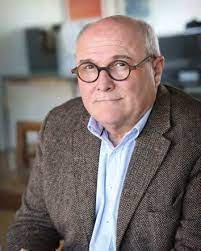

Helios Jermini[113]

From one tale to the next, we arrive at the beginning of the 1970s, when Ultrafin and Gesfid manage the offshore part of the portage activities of Banca del Gottardo and Banco Ambrosiano – and are discovered and identified by Italian magistrates. The real estate assets of the Società Generale Immobiliare, in the meantime bankrupt and sold to one of its subsidiaries, Sogene, are mortgaged, sold several times, hidden from tax audits and burdened with bad debts[114]. Three winners emerged from the liquidation proceedings, initiated in 1976 and led by Nicola Grieco: Grieco himself, the Neapolitan real estate developer Ennio Martinez[115] and Arcangelo Belli, a Freemason and young Roman palazzinaro[116].

Brocchi and Jermini were promoted: from now on they would work under patronage, no longer being direct employees of the Banca del Gottardo[117]. This was the beginning of the period in which Roberto Calvi himself, most probably, had a hard time knowing where what had gone. First there was the separation from the North American real estate assets, which passed through FES AG Zug, founded in 1967, and emptied by Paul Marcinkus. Then there was Eurafric Fininvest, and with this it got serious.

The company was founded in Mauren (Liechtenstein), on 3 June 1969, with money from a numbered account at the United Overseas Bank in Geneva, and a board of directors made up of employees of the ATU[118] – headed by Werner Keicher, Helios Jermini’s point of reference and the Gotthard Bank in Liechtenstein[119]. Jermini became sole director on 18 January 1980, but by then Eurafric already had a decade of militancy at the front – a front which, for the Italian magistrates, remained invisible, defended by the fog of the strenuous defence of Swiss and Liechtenstein laws, which only cooperate when they are really obliged to do so[120].

Eurafric Fininvest, little by little, took control of all the real estate assets and accumulated debts of the Società Generale Immobiliare/Sogene: so Eurafric, on 5 August 1983, was renamed SGC Sogene General Contractors International Etablissement, with a contract signed by Tommaso Sleiter, a former Swiss Vatican guard who had joined the IOR[121], and Nicola Grieco[122]. Jermini resigned on 23 September 1986, by which time the company had been emptied[123]. Martinez shifted the assets he controlled to a series of offshore companies controlled by his family holding company, Yara SA[124] and Belli, together with Jermini, built up a network of companies around the world.

In the meantime, Jermini has a new home: a Liechtenstein-based trust company, Lagestion SA Gamprin, initially owned by Banca del Gottardo[125] , whose offices, however, are in Lugano. Lagestion was founded on 22 July 1975 by Werner Keicher, and counts on the staff that will accompany Jermini for the rest of his life: Donatella Giovanardi (his second wife), Claudio Paltenghi and Giorgio Pelossi – the man for the most complex transactions. They are joined by Emilio Stefanelli, a member of Opus Dei who lives in Monte Carlo as an assistant to Antonio Caroli, one of the mysterious characters who have always revolved around Vatican finance[126].

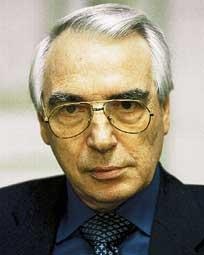

Giorgio Pelossi[127] Werner Keicher[128]

Pelossi is no ordinary man. As a young man, he was sentenced to 17 months in prison by a Ticino court for having swindled some clients out of 700,000 Swiss francs by selling non-existent real estate. Confirmed by Jermini at his side, Pelossi was sentenced to 4 years imprisonment for swindling the shareholders of a mining company of which he was a director out of 3 million Swiss francs. Since then he has been hiding (it seems) in France, but Jermini continues to have him as a partner. The Palermo Public Prosecutor’s Office places him under investigation for his alleged links with the Mafia, and Pelossi goes to live in America as a protected witness. In that capacity, he is arrested again: this time on suspicion of having laundered the proceeds of a drug smuggling operation[129].

From then on, Pelossi becomes truly dangerous: on the run, and desperate, he turns himself in to the German authorities, to whom he confesses to having laundered the money from bribes paid by arms dealer Karlheinz Schreiber to all the CDU leaders, including Chancellor Helmut Kohl, to obtain permission to sell his arms to countries affected by the international embargo. The Augsburg public prosecutor’s office, thanks to Pelossi, uncovered the scandal that swept the entire German political elite, ended the careers of Kohl and other CDU and Liberal Party leaders, and brought the Social Democrats an unexpected electoral victory[130].

For Jermini nothing changes: until his death he will hold on to Pelossi, his clients and his contacts with politics and the underworld[131]. There is a lot of work to be done: between 1975 and 1985, Jermini, through Lagestion, founded 52 companies in Panama, 31 in Liechtenstein, 4 in Monte Carlo, 4 in Curaçao, 6 in Luxembourg, and who knows how many others… these are just the companies that we have managed to trace by meticulously following the traces scattered in the balance sheets and legal documents deposited in the commercial registers. Unfortunately, we do not have the means to search for companies (and there must be many) registered in the United States, Latin America, the Caribbean and the offshore jurisdictions of Africa and the Far East. And Pelossi continues to have other clients: between 2009 and 2010 he got into trouble again for brokering bribes for Canadian Prime Minister Brian Maulroney[132].

All this is hardly surprising. Analysing the hundreds of pages we have collected in almost fifteen years of research, we often come across holding companies, which in turn control other companies that we have not been able to discover anything about. And since, for each company, there is at least one transaction worth millions in loans or property transfers, it is not difficult to estimate the total amount administered by Jermini: at least 7.5 billion, conservatively calculating the change in value between 1980 and today[133]. A figure embezzled over more than a century of Italian public procurement scams by the Società Immobiliare Generale, the IOR, and who knows who else – a figure that took so much substance out of the Roman building holding company that one of the largest real estate companies in history went bankrupt.

It is a figure never pursued by any magistrate, because no one then knew of the existence of Helios Jermini and his partners in Lagestion, and no one ever investigated. The Ticino judiciary could have done so, but did not, and this is certainly not surprising. The Italian police stood firm in the face of Ultrafin and Gesfid, which proved to be insurmountable obstacles in the face of the wall erected by the denials of requests for international rogatory letters from the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Milan or Rome. Here, of course, we cannot analyse a hundred offshore companies, so we will limit ourselves to recounting the most interesting ones – and those which, at the end of the last century, led Jermini to use some of that money to pursue his dream of taking Lugano to the top of European football.

Arcangelo Belli

One of the palaces built by Arcangelo Belli’s firms in Monte Carlo: flats reserved for tax evaders who spend a few weeks a year in Monaco[134]

But we must start at the beginning, or rather with the first beneficiary of the dispersal of the real estate assets of the Società Immobiliare Generale / Sogene: Arcangelo Belli. The first time the name of this Roman palazzinaro rose to the headlines was in 1978, during the weeks of the kidnapping of Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro, which ended with his assassination by the Red Brigades: an event that changed the history of Italy, putting an end forever to the electoral growth of the Communist Party and creating a wave of outraged reaction in the country[135]. Over the years, judicial investigations have shown that it was a convergence of interests that kidnapped and killed Moro, including those of the United States, the Mafia, the secret services and reactionary forces within the Christian Democratic Party: Moro was the architect of the collaboration in government between the DC and the PCI and was kidnapped on the morning when his ‘historic compromise’ government was due to be voted in Parliament[136]

In the days of the kidnapping, the Mafia (through the American boss Francis Turatello) got in touch with Arcangelo Belli, and convinced him that they were able to get Moro back home alive – a negotiation later confirmed by the boss Tommaso Buscetta in his interrogations with judge Giovanni Falcone, which was blocked by the leaders of the DC[137]. Belli proved to know some Mafia bosses so well that he was chosen as a mediator in a negotiation with the leaders of the Christian Democratic Party and Freemasonry – a fact that, in those tragic days, no one found relevant.

On the contrary: Giulio Andreotti, worried by the converging crises that point to him as the epicentre of ‘dirty’ power in Italy, convinces 39 banks to sign an agreement to save the Società Generale Immobiliare for the umpteenth time: SGI sells the finished buildings (including Washington’s Watergate – the building at the centre of the scandal that cost Richard Nixon his career), but keeps the construction sites (in Paris, Boston, Washington, Nairobi and Caracas) and the building land, the banks pay $186 million in cash and $41.6 million in bonds[138].

Belli is chosen as the contract’s custodian (and, therefore, owner of the entire group), without paying a single cent[139], and is given ten years before he starts repaying the loan[140]. A debt that he will never pay because, in 1980, after further plundering, the Società General Immobiliare, with the addition of yet another gift from the Italian government, is sold to Orazio Bagnasco[141] , a financier, a friend of Andreotti[142] , already implicated in the criminal investigations on the Banco Ambrosiano[143] , whose lawyer is Giangiorgio Spiess, Tito Tettamanti’s partner.[144]

Belli had a relatively short career: when, in 2006, we carried out a search of his Italian-registered companies, we discovered that all but one had been liquidated[145]. The family also kept the estates inherited from SGI in Brazil[146]. Riepel AG Eschen (Liechtenstein), founded on 16 March 1972 by Banca del Gottardo, Helios Jermini and Pietro Brocchi[147], appointed Stefanelli in 1978[148] and Belli (president) in 1991[149], when it was the holding company for a number of Panamanian companies[150], some of which are still active today[151]. In 1994, Riepel was sold to Deborah and Francesca, Arcangelo’s daughters, then it was emptied and, in 1999, liquidated[152].

In Panama, Belli founded a company with Mohammed Ali Al Musallam[153] , a Bahraini manager who had made a career in Saudi Arabia[154]. Belli joined Sogene on 24 October 1977, with money from his Habicos SpA, a good 3000 employees[155], of which Jermini owns 5%[156]. Together with Jermini, Stefanelli and other managers from Banca del Gottardo, he founded Habicos International Holding SA Luxembourg which[157], in the best years, earned over 14 million dollars from financial transactions alone[158]. Then, in 1986, the Habicos group was plundered and put into liquidation[159]: an operation so complicated that it was only completed in 2020[160]. Belli was made a knight of labour by the Andreotti IV government[161] at the proposal of Romano Prodi, who was the head of the state holding company IRI as a fervent Christian Democrat[162], and who as Minister of Industry in that government pushed through the ‘Prodi Law’, which allowed the government to spend almost unlimited amounts to support companies in crisis[163].

Antonio Caroli and the Smetra Group

Antonio Caroli, one of the few entrepreneurs in the world to have problems with the Monegasque tax authorities[164]

Smetra Costruzioni SA Lugano was established on 19 June 1962 by Banca del Gottardo (54%) and Epart Etablissement de Participations Financieres Schaan (Liechtenstein)[165] under the name of Grandi Strade SA (set up to win the contract to build the motorway from Chiasso to Gotthard[166]), and changed its name in 1980, when Jermini joined the board of directors and SMETRA Monaco was the sole shareholder[167]. Epart was founded on 19 November 1958 by Banca del Gottardo and Werner Keicher, and Helios Jermini became its chairman as the representative of the sole shareholder, Gisafid SA Lugano, from 1965[168]. Gisafid and Epart, until their liquidation (1985), were controlled by the holding company’s sole shareholder, Sogefinance SA Panama: Helios Jermini[169]. The amount received by Jermini for the sale of the shares in Gisafid and Epart is unknown. The same applies to the Oiechtenstein subsidiary Smetra Anstalt Vaduz[170].

SMETRA Société Monegasque d’Ètudes et de Travaux SA Monaco was founded on 8 June 1976 as a subsidiary of Eurafric Fininvest[171], which is represented on the board by Antonio Caroli[172]. Jermini only entered as a shareholder in 1981[173]. On 30 March 1977, 0.5% was sold to SGI Netherland BV Amsterdam[174] – a share that was increased to 1% in 1979. In 1979[175], both Belli and Stefanelli bought 1 share in the company (0.075%)[176]. On 26 November 1980, SGI Sogene International Ltd. Monrovia (Liberia) acquires 48.93% of the company[177]. SGI Sogene International confers to Smetra Monaco 10% of Société Civile Immobilière Soleil d’Or SA Monaco, 44% of Iemanja SA Monaco and 100% of Samegi SA Montecarlo[178].

Each of these participations corresponds to at least one multimillion-dollar construction contract. As of June 1983, 88.44% of the company belongs to Smetra Investment Curaçao, and 10.01% to Antonio Caroli – the rest is in the hands of Jermini and Belli[179]. The following year, Arcangelo Belli resigned and left the company[180]. Until the end of 1993, Smetra Monaco distributes a dividend on profits of between 9 and 20 million French francs (between 1.37 and 3.05 million euros[181]) per year – a coupon of about a quarter of the profits made by Smetra[182]. From 1994 onwards, Jermini and Caroli slowly began to empty this company too, increasing its debts and transferring part of the profits to new companies (such as Smetra France, SCPM Fondimmo SA Monaco and Finges SA Monaco)[183].

From 1999 onwards, things steadily improved: Jermini left the company, replaced by Alex Caroli, Antonio’s son[184]. But the most important event is another: as of 1991 Smetra Investment Curaçao no longer belongs to Belli and Jermini, but was sold to Atruka International Trust NV Willemstad, which now controls 88.44% of the Smetra Group[185]. Atruka is a trust company founded by Lagestion SA (Jermini) to hide the assets taken from the bankruptcy estate of Sogene[186]. Other companies in the group: Smetra Netherland BV Amsterdam, which belongs to Smetra Investment Curaçao NV Willemstad, which was founded on 18 November 1980 by Helios Jermini and Arcangelo Belli[187] , is sold, together with SGI International BV of Rotterdam, to Bluefin Investments Limited of Mauritius[188].

A thousand crumbs of Sogefinance

A picture of the staff of the fiduciary firm Tapia & Asociados, which administered most of the Panamanian companies managed by Jermini[189]

Helios Jermini remains, little by little, the last guardian of a whole series of companies that have been sold off to avoid being discovered by the magistrates: companies with sometimes laughable, sometimes important assets. Sometimes they are offshore companies used for a single transaction, sometimes they are real industrial companies – like the Espada group. It was founded as Espada Finanziaria SA Chur on 4 December 1969 by Banca del Gottardo. On 13 June 1978 Emilio Stefanelli was elected to the board of directors, and a few months later, on 22 January 1979, Jermini was also elected. Only in 1987 was this staff replaced by Sogene’s liquidator, Nicola Grieco[190].

Manubren SA Davos was founded on 7 July 1972 by Banca del Gottardo, he administered it from day one, assisted by Emilio Stefanelli from 26 October 1978. This company was also taken over by Grieco in 1987[191], but until then, and since 3 January 1979, it had been part of the Sogefinance group, administered by Jermini[192]. In 1997, Grieco sold Manubren to Espada Trust Vaduz, which probably belongs to David John Titman, who already controls the Spanish (and possibly also Portuguese) subsidiaries of both Espada and Manubren[193]. This makes the case of Espada and Manubren a special one: someone knew of their existence, and they were dealt with in the liquidation procedure of the General Real Estate Company.

But most of the companies founded by Banca del Gottardo in Panama and Lichtenstein, and controlled first by SGI International Ltd. Monrovia, then by Sogefinance[194], escaped both the liquidators of Sogene and those of Banco Ambrosiano. Some, such as Immofinbet[195] and Rentia Anstalt[196] in Vaduz, already existed in the 1950s, the others came into existence after Jermini was moved to Gisafid first, and then to Lagestion, and mostly remained operational until the death of the Ticino trustee[197]. In Panama, the list is even longer[198] – and nothing is known about any of these companies, because they were neither the subject of liquidation nor of the Sogene bankruptcy investigations.

Lagestion’s trustees are not greedy people, they do not live in luxury, nobody, not even in Lugano, has ever noticed them – until Jermini decides to buy FC Lugano and take it to international level: a crazy operation, for a team that, in its Cornaredo stadium, rarely sees more than 3000 paying spectators. But it doesn’t matter: it’s a dream, and at 60 years of age for a man who, for years, had had immense power, without anyone noticing, it’s an irresistible temptation. The money is there: for Jermini and his staff it’s a dangerous situation at first, then increasingly comfortable: being administrators of these companies, they know the details of the bank accounts, and can take as much money as they want, limiting themselves (when the money is gone) to liquidating a company that no one would ever notice. Or hardly anyone…

Epilogue: FC Lugano and the Opus Dei axe

The palace in Via Ciro Menotti, Rome, where David John Titman met clients and prelates[199]

The theory developed by the magistrates to explain the murder of Roberto Calvi has not been proven in court[200]. After long years of investigations, it seems clear that Mafia, Freemasonry and Vatican prelates, all involved (as clients) in the system set up to use Banco Ambrosiano and Banca del Gottardo as the ganglion of a huge money-laundering and production machine, had an interest in seeing Calvi dead, before the Italian justice system had convinced him to tell all he knew[201].

There were also attempts to involve Opus Dei, but these were not supported by sufficient evidence[202]. More than 40 years later, the last word on Banco Ambrosiano has still not been written. What is historically certain, however, is that this para-religious organisation was involved in the dismantling and debt collection of Sogene / Società Generale Immobiliare – a necessary involvement for the Holy See, which also used the Società Generale Immobiliare and its financial, land and real estate holdings to generate cash, and which ultimately ended up with a pile of debts in its hands[203].

After futile attempts to obtain clarity within the Vatican management, Opus Dei’s leaders instructed an English lawyer, David John Titman, to move to Rome and sort out, one by one, all the financial grievances, and use every possible way to identify the parts of the assets hidden by anyone that could still be recovered[204]. And it is Titman who puts an end to Jermini’s carefree days, because someone in Italy leaks his name, and Titman has an organisation behind him capable of finding the necessary information anywhere, and of defending his own reasons in any court.

In Italy, Titman registers an intermediary company, Interserv Srl[205], and is responsible for identifying, everywhere in the world, the assets that are to be returned to Opus Dei. Among the first discoveries are SMETRA and Eurafric Fininvest: once he has read the official papers, Titman takes Smetra Investment Curaçao and SGI International of Monrovia to court in Monte Carlo[206]. With that trial, Titman obtains share control over the Liberian SGI and, from this conquest, begins his battle to recover the money that has disappeared around the world[207].

Meanwhile, Jermini is in the midst of a struggle to save FC Lugano from bankruptcy. Until the spring of 1994, the owner is the Banca del Gottardo, represented by its director Francesco Manzoni. Suddenly, Manzoni leaves the bank and moves to Monte Carlo, where he buys the local branch of the Banca del Gottardo from the bankruptcy auction and, since then, manages it together with a couple of partners. A chilling solution, which leaves open several questions, to which the Ticino judiciary has refused to find answers, and which leaves FC Lugano facing the prospect of bankruptcy: Manzoni leaves a hole of 32 million francs – a chasm – in his inheritance[208].

26 May 1995: The captain, Christian Colomba, dribbled past Riccardo Ferri and initiated the action that led to José Carrasco’s goal, thanks to which Lugano eliminated Inter from the UEFA Cup[209]

Helios Jermini jumped into the fray, became the new president and owner of the club, paid off some of the unpayable debts and promised to put together a great team. Two years later, after the team had bought several players from the national teams of Brazil, Sweden and Holland[210], Lugano eliminated Inter from the UEFA Cup[211]. But this changes nothing: Lugano’s youth is passionate about ice hockey, and does not go to the stadium for football. When, after three years, it comes to paying off a debt that has risen from 32 to 45 million, Jermini realises he cannot cope and decides to quit – an impossible step, because his resignation would not only mean the end of the club, but also an investigation into him, his collaborators and his business dealings.

But rumours are already circulating, and it turns out that the money to pay Lugano comes from two Liechtenstein finance companies that, however, still belong to Jermini[212]. A request from the Swiss football federation as to where that money came from remains unanswered – because those companies exist to take over the team’s debts, not to pay them. At the same time, an Italian client of Jermini’s turned to the Ticino judiciary (unsuccessfully) to get back the money that the Lugano president had allegedly stolen from him[213], but it was the sign that everyone feared: Jermini is not capable of running FC Lugano. With no more friends or protectors, the time for a showdown has arrived.

First of all with Titman. On 26 June 1996, his lawyers filed an injunction against BSI Banca della Svizzera Italiana at the Pretura di Lugano – the umpteenth after more than a decade of useless official acts[214]. One of the companies he administers, Wentworth SA Lugano, has claims against the bank for over 16 million dollars – plus, evidently, years of accrued interest[215]. Wentworth is controlled by SGI International Ltd. Monrovia, and by Promotion Investment Curaçao NV Willemstad – the former is a company administered by Jermini which, in the course of the recapitalisation of the Sogene / Società Generale Immobiliare group, was sold to Opus Dei, and the latter was specifically set up by Titman to bring together all the offshore companies recovered from Sogene and transformed into assets[216].

The BSI admits to having that money, but claims it is collateral for outstanding credits – credits that Jermini and Belli used to buy some real estate companies and land in Venezuela[217]. The issue is not new: allegedly, BSI, when it was still under the influence of shareholder Tito Tettamanti, participated in the portage carousel, granting loans without real guarantees. The result: figuring out, in retrospect, who owes money to whom (since both the bank and SGI did everything possible to conceal the content of the transactions), is now impossible. It is possible that that money is, in fact, no longer there and that the bank is (obviously) having trouble admitting it – as in the case of Banca del Gottardo, which over the years has paid out millions to Jermini, without him having to justify it, because he had the portage contract in his pocket[218].

But the lawyer Titman cannot let go of the bone, because behind the Wentworth case is the biggest and most dangerous case: a bank, which Titman does not name, has the millions that SGI of Monrovia earned from rents and other services related to the construction of Watergate House[219] – the building, rented by the American Democratic Party, which was spied on at the behest of Richard Nixon, which led to a scandal of worldwide proportions and the resignation of the president[220]. When, shortly after Jermini’s death, I met Titman, all he said was: “Are you tired of living?” On 21 February 2002, a few hours before Jermini’s death, Titman wrote a second letter, in which he clearly threatened the Ticino trustee…[221]

The colossal building housing the Gotthard Bank, designed by the famous architect Mario Botta[222]

The story ends in tragedy: on 5 March 2002, Jermini, driving his Audi along a winding road along Lake Lugano, allegedly pulled straight, at full speed, into a sharp bend – the car flew over the embankment, into the lake, and Jermini drowned[223]. I personally visited the site of the accident, and it seemed impossible that a car could drive off the road at full speed, because it’s a stretch that already becomes dangerous at 50kmh: it doesn’t matter, for the police it’s suicide. Apparently he had attempted an extreme miracle the night before, offering to launder money from Russian organised crime[224] – too late.

A few hours later, Lugano’s prosecutor, Emanuele Stauffer (who will become bank director after this investigation[225]) closes all investigations against Lugano and against Jermini’s companies. His point of reference at the Banca del Gottardo, director Gianluca Gamba, died of a heart attack a few hours later, without ever having testified[226]. Jermini’s assistant in charge of Lugano Calcio’s contracts, Philipp Steinegger, dies in exactly the same way and in exactly the same place as Jermini, exactly six months after his boss[227], the day before he was to be interrogated by the Ticino judiciary. Lugano did not go bankrupt: the courts allowed all debts to be transferred to Vaduz, and the team started from scratch. In Liechtenstein, a solution was found within a few years, but it remains a secret.

No sign of this remains: the Gotthard Bank was sold a couple of times, then liquidated. The Sogefinance companies were closed, as were the companies of the Smetra group. Arcangelo Belli has died of old age, all the others are now out of the business, all that is known of Titman is that he has moved to South America. This confirms something I have always believed: the real history of the 20th century will perhaps be known by my grandchildren’s children.

[1] https://romaarcheologiaerestauroarchitettura.wordpress.com/2021/01/16/roma-archeologica-restauro-architettura-2021-roma-la-villa-mills-sul-palatino-di-jahn-autoro-rusconi-1906-alfonso-bartoli-1908-in-pdf-foto-roma-villa-mills-operai-a-lavoro-per/

[2] https://www.openstarts.units.it/bitstream/10077/10012/1/Manenti_phd.pdfhttps://www.openstarts.units.it/bitstream/10077/10012/1/Manenti_phd.pdf

[3] https://www.pandorarivista.it/articoli/la-massoneria-in-italia-dall-unita-alla-nascita-della-repubblica-intervista-a-fulvio-conti/

[4] https://www.lidentitadiclio.com/massoneria-italia-storia-logge-e-simboli/

[5] https://www.storiologia.it/cattaneo/doc1802.htm

[6] https://notiziariomassonicoitaliano.blogspot.com/2010/08/la-massoneria-dopo-lunita-ditalia-2.html

[7] https://www.comitatiduesicilie.it/31/12/2018/il-paese-della-tragicommedia-lincontro-di-teano-tra-giuseppe-maria-garibaldi-e-vittorio-emanuele-di-savoia-una-farsa-tutta-italiana/

[8] https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2004/02/28/menotti-teresa-ricciotti-garibaldi-dopo-garibaldi.html

[9] Enzo Magri, I ladri di Roma. 1893 scandalo della Banca Romana: politici, giornalisti, eroi del Risorgimento all’assalto del denaro pubblico, Arnoldo Mondadori, Milano 1993

[10] http://2.42.228.123/dgagaeta/dga/uploads/documents/PIA/5fe2ebb966e8d.pdf, pages 66-76

[11] John F. Pollard, Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, page 205

[12] https://www.chiesaecomunicazione.com/doc/lettera-enciclica_annum-ingressi_1902.php ; https://www.pandorarivista.it/articoli/la-massoneria-in-italia-dall-unita-alla-nascita-della-repubblica-intervista-a-fulvio-conti/ ; https://www.famigliacristiana.it/articolo/ecco-cosa-dice-monsignor-galantino-sulal-massoneria.aspx ; https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19810217_massoni_it.html

[13] Alberto Statera, Storia di preti e di palazzinari, L’Espresso, Milano 1977; Enzo Magri, I ladri di Roma. 1893 scandalo della Banca Romana: politici, giornalisti, eroi del Risorgimento all’assalto del denaro pubblico, Arnoldo Mondadori, 1993

[14] https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/2015-11-25/ty-article/1907-a-jew-becomes-mayor-of-rome/0000017f-f53b-ddde-abff-fd7f0dad0000

[15] https://www.micromega.net/ernesto-nathan-un-grande-laico-un-grande-sindaco/ ; https://mondoeconomico.eu/archivio/agenda-liberale/chiamulera-7-giugno

[16] John F. Pollard, Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, page 205

[17] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/partito-popolare-italiano_%28Cristiani-d%27Italia%29/

[18] VATICANO E FRATELLI MUSULMANI: UN SECOLO DI RELAZIONI POLITICHE E FINANZIARIE | IBI World Italia

[19] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/partito-popolare-italiano_%28Cristiani-d%27Italia%29/ ; https://www.jstor.org/stable/43050211

[20] https://romeguides.it/2022/06/02/ernesto-nathan-gran-maestro-massone/

[21] https://www.vatican.va/content/romancuria/it/uffici/amministrazione-del-patrimonio-della-sede-apostolica/profilo.html

[22] Luigi De Rosa, Gabriele De Rosa, Storia del Banco di Roma, Volume III, Banco di Roma, Roma 1984, pages 101-102; John F. Pollard, Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, page 205

[23] Luigi Sturzo, Emanuela Sturzo, “Carteggio (1891–1948)”, Rubbettino, Roma 2000, page 62

[24] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-boncompagni-ludovisi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/

[25] Franco Cotula, Luigi Spaventa, “La politica monetaria tra le due guerre: 1919-1935”, Laterza Editore, Roma 1993, page 914; Maurizio Pegrari, “L’Unione bancaria nazionale: nascita, ascesa e declino di una grande banca lombarda, 1903-1932”, Grafo, Roma 2004, pages 75 and 171; https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/de-pecunia-chiesa-cattolici-e-finanza-nello-stato-unitario_%28Cristiani-d%27Italia%29/

[26] https://portaledelfascismo.altervista.org/mussolini-e-il-papa-la-chiesa-durante-il-fascismo/ ; https://www.noisefromamerika.org/articolo/papa-mussolini

[27] https://www.jstor.org/stable/26142591 ; https://notes9.senato.it/Web/senregno.NSF/d7aba38662bfb3b8c125785e003c4334/2d902456947eed0b4125646f00592081?OpenDocument

[28] https://www.normattiva.it/atto/caricaDettaglioAtto?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1929-06-05&atto.codiceRedazionale=029U0810&tipoDettaglio=originario&qId=&tabID=0.6230481932172793&title=Atto%20originario&bloccoAggiornamentoBreadCrumb=true

[29] (JER) 1997.03.23 The Economist on Sasea

[30] (JER) 1997.03.23 The Economist on Sasea, Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, UnionsVerlag, Zurigo 1996, pages 326-356

[31] https://roma.corriere.it/amministrative-2016/cards/i-sindaci-roma-dopoguerra-oggi/umberto-tupini.shtml

[32] http://2.42.228.123/dgagaeta/dga/uploads/documents/PIA/5fe2ebb966e8d.pdf, pages 26-35 ; http://sttan.it/appunti/urbanistica/prof_Tilocca/Il%20Dopoguerra%20e%20La%20Ricostruzione/dopoguerra&ricostruzione.html

[33] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/de-pecunia-chiesa-cattolici-e-finanza-nello-stato-unitario_%28Cristiani-d%27Italia%29/

[34] https://www.jstor.org/stable/20566915 ; https://www.jstor.org/stable/20566759 ; https://legrandcontinent.eu/it/2021/08/19/mediobanca-e-la-geopolitica-della-finanza-dal-marshall-plan-al-recovery-plan/

[35] https://espresso.repubblica.it/attualita/2015/09/01/news/capitale-corrotta-nazione-infetta-l-inchiesta-scandalo-di-manlio-cancogni-sull-espresso-1.227113?refresh_ce

[36] https://www.academia.edu/39140193/ROMA_LE_RAGIONI_DI_UN_DECLINO_APPUNTI_SULLA_SPECULAZIONE_URBANISTICA_DEL_DOPOGUERRA_VERSIONE_COMPLETA_CON_IMMAGINI_

[37] http://2.42.228.123/dgagaeta/dga/uploads/documents/PIA/5fe2ebb966e8d.pdf, pages 98-103

[38] https://www.academia.edu/30213226/LAFFARE_OLIMPIADI_9_pdf ; https://www.aromaweb.it/articoli/speciale/eur/

[39] https://espresso.repubblica.it/attualita/2015/09/01/news/capitale-corrotta-nazione-infetta-l-inchiesta-scandalo-di-manlio-cancogni-sull-espresso-1.227113?refresh_ce

[40] https://lavocedinewyork.com/lifestyles/sport/2016/08/24/roma-olimpica-ieri-oggi-e-domani/

[41] Italo Insolera, Roma moderna: un secolo di storia urbanistica, Einaudi, Torino 1983

[42] https://www.lastampa.it/cronaca/2010/09/22/news/la-banca-del-papa-1.37001684/

[43] https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1999/09/06/banca-del-gottardo-lo-scandalo-nei-geni.html ; https://consumatori.ch/site/article.php?id=2504&riv=3&max_char2=1

[44] (JER) Lovelok Establishment Vaduz; Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, Unionsverlag, Zurigo 1996, pages 261-262

[45] https://www.lastampa.it/cronaca/2010/09/22/news/la-banca-del-papa-1.37001684/

[46] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2013/07/radowall-ior-e-laffaire-banca-cattolica.html

[47] (JER) 1971.07.27 IOR a Compendium

[48] (JER) Compendium SAH Luxembourg, pages 220-236; (JER) Banco Ambrosiano Holdings SA Luxembourg, pages 238-253; https://www.trentaminuti.it/roberto-calvi-tanti-miliardi-venuti-dal-nulla.html

[49] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2013/07/radowall-lorigine-dei-rapporti-con-mons.html

[50] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2013/07/radowall-ior-e-laffaire-banca-cattolica.html

[51] https://www.romecentral.com/en/cento-anni-dalla-nascita-di-giulio-andreotti-in-mostra-le-fotografie-della-sua-vita/a-sinistra-giulio-andreotti-1919-2013-a-colloquio-in-vaticano-con-il-papa-pio-xii-1876-1958-nel-1953-farabolafoto/

[52] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2013/07/radowall-lorigine-dei-rapporti-con-mons.html

[53] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2013/05/ior-utc-e-quei-223-milioni-di-dollari-1.html

[54] (JER) Compendium SAH Luxembourg, pages 220-236

[55] https://moondo.info/michele-sindona-chi-era/

[56] http://amsdottorato.unibo.it/7294/1/D%27ADDEA_OTTAVIO_TESI.pdf, pages 160-165 ; https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/962/giulio-andreotti-corruption-murder-and-the-thirst-/

[57] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 264 ; https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1979/01/10/david-kennedy-testifies-to-link-with-sindona/d664e6be-46f1-4f84-bc2a-838b7cba7b07/ ; https://www.repubblica.it/2006/b/sezioni/esteri/marcinkus/commestatera/commestatera.html ; https://www.heritage-history.com/index.php?c=read&author=compton&book=broken&story=part6 ; https://www.motherjones.com/politics/1983/07/banking-godthe-mob-and-cia/

[58] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 264

[59] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v19p2/d100 ; https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/rr171x89h?locale=en

[60] https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/finding-aids/fg-263-commission-international-trade-and-investment-policy-white-house-central-files

[61] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/amleto-giovanni-cicognani_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

[62] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2013/05/07/andreotti-potere-e-misteri2-premier-e-rapporto-con-sindona-e-lambrosoli-dimenticato/586010/

[63] Davide Conti, L’Italia di Piazza Fontana: alle origini della crisi repubblicana, Einaudi, Torino 2020

[64] http://www.dellarepubblica.it/v-legislatura-i-rumor, page 3120

[65] C. Ruta, Il processo. Il tarlo della Repubblica, Eranuova edizioni, Perugia 1994; Giuseppe De Lutiis, Storia dei servizi segreti in Italia, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1985

[66] SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA-CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI, XII LEGISLATURA, Doc. XXXIV, n. 1, RELAZIONE DEL COMITATO PARLAMENTARE PER I SERVIZI DI INFORMAZIONE E SICUREZZA E PER IL SEGRETO DI STATO, § 4.2: «Appare credibile quanto affermato a suo tempo dall’ingegnere Francesco Siniscalchi e dai dottori Ermenegildo Benedetti e Giovanni Bricchi circa una possibile donazione di fascicoli che l’ex capo del SIFAR Giovanni Allavena avrebbe effettuato a Gelli al momento di aderire alla loggia P2 nel 1967. Negli anni successivi, inoltre, l’adesione alla loggia di pressoché tutti i principali dirigenti del SID rende più che plausibile un travaso informativo da questi ultimi a Gelli»; Sergio Flamigni, Dossier Pecorelli, Kaos editore, Milano 2005; Giorgio Boatti, Enciclopedia delle spie, Rizzoli, Milano 1989, pages 140-141; https://www.scenacriminis.com/tag/fascicoli-sifar/ ; https://www.indygesto.com/dossier/11554-pecorelli-e-i-fascicoli-del-sifar-una-profezia-di-op

[67] https://www.americancreed.org/cast-david-m-kennedy

[68] https://storia.camera.it/cronologia/leg-repubblica-V/elenco

[69] Davide Conti, L’Italia di Piazza Fontana: alle origini della crisi repubblicana, Einaudi, Torino 2020; https://www.resistenze.org/sito/os/ip/osip2i09.htm

[70] [70] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 264 and 359

[71] Gianluigi Nuzzi, Vatikan AG. Ein Geheimarchiv enthüllt die Wahrheit über die Finanz- und Politskandale der Kirche. Ecowin, Salzburg 2009; Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, Unionsverlag, Zurigo 1996, pages 264 and 359; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michele-Sindona#ref225355 ; https://www.nytimes.com/1964/07/24/archives/fasco-offer-to-buy-stock-of-brown-co-successful.html ; https://www.lexoffice.de/lexikon/briefkastenfirma/

[72] https://www.tesionline.it/appunti/lettere-e-filosofia/storia-contemporanea/le-riforme-del-1968-in-italia/613/84

[73] http://www.thechillerinside.com/2018/01/case-file-roberto-calvi.html

[74] http://fourwinds10.com/journals/UnPublished/J164.pdf, pages 58-64

[75] (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, page 18

[76] https://entreprendre.service-public.fr/vosdroits/F31620 ; https://www.itg.fr/portage-salarial/umbrella-company.html

[77] https://www.consulenzalegaleitalia.it/lettera-di-patronage/

[78] (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, pages 13-18

[79] (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, pages 84-89

[80] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2014/12/

[81] Zwillfin AG Balzers, Beverfin AG Eschen, Saberal AG Triesen, Teclefin AG Eschen, Inparfin AG Vaduz, Chatoser Anstalt Vaduz – see in (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, pages 374-375

[82] (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, pages 374-375

[83] (JER) Manic SA Holding Luxembourg

[84] (CAL) Patronage IOR Gottardo, passim

[85] Microsoft Word – Angola Report 13. Draft.doc (ibiworld.eu), pages 11-12

[86] https://www.dw.com/en/espirito-santo-group-how-it-all-started/a-17804754 ; https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/empresas/a-casa-dos-espiritos-parte-i-12655601.html

[87] https://www.euromoney.com/article/b1320djt45n2f9/portuguese-banking-aristocracy-time-for-family-planning ; https://www.colectivoburbuja.org/javier-barrajon/felix-millet-banco-popular-opus-dei/ ; https://www.journal21.ch/artikel/das-ende-der-unantastbarkeit

[88] https://www.northdata.de/Ultrafin+AG,+Lugano/CHE-102.337.333 ; https://liechtensteincompanies.com/gesellschaft/ultrafin-ag-4mB

[89] Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, Unionsverlag, Zurigo 1996, traduzione italiana (2009), pages 126-130

[90] https://www.zefix.admin.ch/de/search/entity/list/firm/13498

[91] Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, Unionsverlag, Zurigo 1996, traduzione italiana (2009), pages 176-177

[92] Gian Trepp, Swiss Connection, Unionsverlag, Zurigo 1996, traduzione italiana (2009), page 176

[93] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Etendard_en_1982.jpg

[94] https://fraudauditing.blogspot.com/2014/12/

[95] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxkiLxZ1TlA

[96] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 224

[97] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 224

[98] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 224

[99] http://fncrsi.altervista.org/Morte_Mussolini_misteri_viaggio_a_Moltrasio.htm ; Giorgio Cavalleri, Ombre sul lago. I drammatici eventi del Lario nella primavera-estate 1945, Edizioni Arterigere, Como 2007, pages 32-33

[100] http://200.2.15.132/bitstream/handle/123456789/43582/hm003619561205.pdf?sequence=2

[101] (JER) Interchange Bank on Nexis

[102] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, page 224

[103] 1993.03.24 (MAF) (FIMO) Urteil Fimo

[104] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, pages 358-359

[106] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, pages 224-225

[107] (JER) Banca Gesfid SA Lugano

[108] https://www.pkb.ch/de/pkb/storia.html

[109] https://www.pkb.ch/de/pkb/governance-carriere/consiglio-di-amministrazione/umberto-trabaldo-togna.html

[110] http://arcangelo-gamaz.blogspot.com/2010/09/larcangelo-42-10-biella-ticino.html ; https://incognitoveritatemservio.wordpress.com/2018/12/20/le-mani-sulla-ramazzotti-vol-1/

[111] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L-DNO4bFp1c ; https://www.agoravox.it/Berlusconi-e-la-Banca-Rasini.html ; http://www.aurorarivista.it/articolo.php?cat=memoriatt&id=155_banca_rasini__a ; https://www.repubblica.it/online/ventirighe/chi/chi/chi.html?ref=search

[112] https://www.lesechos.fr/2004/02/une-filiere-suisse-emerge-dans-lenquete-sur-le-scandale-parmalat-630783 ; http://www.ecn.org/antifa/article/6257/latina-le-collusioni-mafiose-di-lega-e-fratelli-ditalia ; https://parma.repubblica.it/dettaglio/parmalat-la-finanziaria-privata-di-collecchio/1657806 ; https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/caso-cardon-le-carte-dell-indagine-spunta-fiduciaria-finanziere-tettamanti-AEZry15G

[113] https://www.news.ch/Helios+Jermini+veruntreute+61+Millionen/112312/detail.htm

[114] https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1987/03/29/deciso-il-concordato-per-la-sgi-sogene.html ; https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1987/03/27/il-malinconico-tramonto-della-sogene.html ; https://www.sissco.it/recensione-annale/paola-puzzuoli-a-cura-di-la-societa-generale-immobiliare-sogene-storia-archivio-testimonianze-2003/

[115] http://www.lavocedellevoci.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Inchiesta-Voce-ottobre-90.pdf

[116] https://parlamento16.openpolis.it/atto/documento/id/72159

[117] http://www.archivioflamigni.org/doc/indice-atti-commissione-p2.pdf, pages 135-136 ; http://arcangelo-gamaz.blogspot.com/2010/09/larcangelo-42-10-biella-ticino.html ; https://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/DF/283909.pdf

[118] (JER) Eurafric Vaduz, pages 1-3

[119] Paolo Fusi, Il Cassiere di Saddam, Consumedia, Bellinzona 2003, Capitolo VI

[120] (JER) Eurafric Vaduz, pages 10-12

[121] (JER) Eurafric Vaduz, pages 14-17

[122] (JER) Eurafric Vaduz, pages 19-20

[123] (JER) Eurafric Vaduz, pages 27-28

[124] http://www.lavocedellevoci.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Inchiesta-Voce-ottobre-90.pdf

[125] (JER) Lagestion Vaduz, page 6

[126] (JER) Lagestion Vaduz, pages 1-22

[127] https://docplayer.org/172307257-Es-kommt-alles-raus-der-platz-des-patriarchen-blieb-nicht.html

[128] https://www.atu.li/Portals/0/download/andere-publikationen/Jubilaeumsbeilage-90-Jahre-ATU.pdf?ver=2019-04-02-090432-657

[129] 2000.01.30 (JER) Von wegen Ehrenmann

[130] https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/ehemaliger-schreiber-mitarbeiter-kohl-hat-gelogen-a-69534.html ; https://www.welt.de/print-welt/article490221/Pelossi-Habe-500000-Dollar-an-Thyssen-Manager-uebergeben.html ; https://www.bz-berlin.de/archiv-artikel/schreiber-luegt-er-hat-unsere-familie-zerstoert ; https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/urteil-im-schreiber-prozess-beispiellose-uneinsichtigkeit-1.939280-2 ; (JER) Belli Presse

[131] (JER) Lagestion Vaduz

[132] (JER) Pelossi in Canada on Nexis

[133] https://www.infodata.ilsole24ore.com/2021/09/03/quanto-valevano-soldi-nel-passato-calcolatore-andare-indietro-nel-tempo/

[134] https://arcangelobelli.com/en/principato-di-monaco/

[135] Sergio Zavoli, La notte della Repubblica, Nuova Eri, Roma 1992; Carlo Alfredo Moro, Storia di un delitto annunciato, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1998; Valerio Morucci, La peggio gioventù, Rizzoli, Milano 2004; Andrea Colombo, Un affare di Stato. Il delitto Moro e la fine della Prima Repubblica, Cairo Editore, Milano 2008; Sergio Flamigni, La tela del ragno. Il delitto Moro, Edizioni Associate, Roma 1988

[136] Sergio Zavoli, La notte della Repubblica, Nuova Eri, Roma 1992; Carlo Alfredo Moro, Storia di un delitto annunciato, Editori Riuniti, Roma 1998; Valerio Morucci, La peggio gioventù, Rizzoli, Milano 2004; Andrea Colombo, Un affare di Stato. Il delitto Moro e la fine della Prima Repubblica, Cairo Editore, Milano 2008; Sergio Flamigni, La tela del ragno. Il delitto Moro, Edizioni Associate, Roma 1988

[137] 2002.04.11 (JER) Belli Presse, pages 1-3

[138] (JER) Arcangelo Belli on Nexis, pages 4-6

[139] http://www.lavocedellevoci.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Inchiesta-Voce-ottobre-90.pdf

[140] (JER) Arcangelo Belli on Nexis, pages 4-6

[141] (JER) Arcangelo Belli on Nexis, pages 7-8

[142] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, pages 341-343

[143] https://ulis-buecherecke.ch/pdf_infos_zur_schweiz/swiss_connection.pdf, pages 275-276

[144] https://forum.termometropolitico.it/283037-tanzi-cragnotti-berlusconi-canali-finanziari.html ; http://www.berlusconis.altervista.org/affari/start.htm?cap2.htm ; https://www.lettera43.it/arturo-artom-un-riciclato-alla-corte-dei-5-stelle/?refresh_ce

[145] 2006.01.19 (JER) Arcangelo Belli

[146] (JER) Arcangelo Belli on Nexis, pages 44-47 ; https://opencorporates.com/companies/br/79347290000102

[147] (JER) Riepel Vaduz, pages 1-9

[148] (JER) Riepel Vaduz, pages 11-13

[149] (JER) Riepel Vaduz, pages 42-44

[150] 1982.01.25 (JER) Racardia Holding Inc Panama; 1981.11.05 (JER) Middle Eastern and European Investments Company Inc Panama; https://opencorporates.com/companies/pa/174925 ; https://opencorporates.com/companies/pa/174828 ; https://opencorporates.com/companies/pa/153167

[151] https://www.mercado.com.pa/ejecutivos/arcangelo-belli-id-7D059AF16A2FD1B0

[152] (JER) Riepel Vaduz, pages 54-69

[153] 1981.11.05 (JER) Middle Eastern and European Investments Company Inc Panama

[154] https://prabook.com/web/mohammed_ali.al-musallam/549648 ; http://abc-bahrain.com/companies/8145/uco-marin-contracting-wll

[155] https://www.quirinale.it/onorificenze/insigniti/836

[156] (JER) Atti Habicos, page 16

[157] 1977.10.24 (JER) Gruendung Habicos

[158] (JER) Bilanci Habicos

[159] https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1987/07/18/la-sogene-travolge-belli.html

[160] (JER) Fallimento Habicos

[161] https://www.quirinale.it/onorificenze/insigniti/836

[162] https://web.archive.org/web/20080210025134/http://www.governo.it/Presidente/Biografia/biografiaProdi_it.html

[163] https://www.tesionline.it/news/cronologia.jsp?evid=3813

[164] https://www.monacomatin.mc/vie-locale/exclusif-antonio-caroli-je-suis-toujours-dispose-a-chercher-une-conciliation-avec-letat-533674

[165] 1962.06.19 (JER) Smetra Lugano

[166] https://www.fpct.ch/documenti/FPC12_SEI_Mendrisio.pdf

[167] 1962.06.19 (JER) Smetra Lugano

[168] 1958.11.19 (JER) Epart

[169] 1958.11.19 (JER) Epart

[170] (JER) Smatra Vaduz

[171] Smetra Monaco, pages 1-2

[172] Smetra Monaco, pages 13-18

[173] Smetra Monaco, pages 65-69

[174] Smetra Monaco, pages 7-11

[175] Smetra Monaco, page 18

[176] Smetra Monaco, pages 32-37

[177] Smetra Monaco, pages 48-52

[178] Smetra Monaco, pages 62-63; 1981.06.26 (JER) Samegi Monaco

[179] Smetra Monaco, pages 73-82

[180] Smetra Monaco, pages 88-98

[181] https://it.coinmill.com/

[182] Smetra Monaco, pages 32-168

[183] Smetra Monaco, pages 169-218

[184] Smetra Monaco, pages 219-224

[185] 1991.09.06 (JER) Lettera di Smetra Curaçao

[186] 1991.09.20 (JER) Atruka

[187] (JER) Smetra Curaçao

[188] (JER) Smetra Curaçao

[189] https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=449846106730284&id=100165788364986&m_entstream_source=permalink

[190] (JER) Espada Chur, pages 1-6

[191] (JER) Espada Chur, pages 7-13

[192] 1979.01.02 Sogefinance Société de Gestion et de Financements SA Panama

[193] https://www.infoempresa.com/es-es/es/directivo/david-john-titman#search-leaders

[194] 1979.01.02 Sogefinance Société de Gestion et de Financements SA Panama

[195] (JER) Immofinbet Vaduz, pages 1-15

[196] (JER) Rentia Anstalt Eschen

[197] 1961.11.16 (JER) Finrever; 1962.10.11 (JER) MAFININVEST; 1966.05.03 (JER) Garnitur Vaduz; 1970.05.06 (JER) DERAL ANSTALT Vaduz; 1970.09.30 (JER) Bocano Anstalt Mauren; 1972.01.17 (JER) Socofina Vaduz; 1973.03.15 (JER) Gestinvest Anstalt Anstalt Vaduz; 1977.07.13 (JER) Elektrometall; 1978.02.17 (JER) Exintra Vaduz; 1982.09.16 (JER) Cartin Vaduz; 1982.10.26 (JER) Gestor Vaduz; 1983.11.15 (JER) Seimor AG Vaduz; 1985.06.18 (JER) GESON ANSTALT Vaduz; 1988.05.16 (JER) HABI TRUST Vaduz; 1994.08.11 (JER) Monotex AG Vaduz; 2000.06.09 (JER) Erste Safina Anstalt Vaduz

[198] 1968.05.08 (JER) La Costuracca Compania Naviers SA Panama; 1971.03.01 (JER) I E I International Engineering Investment SA Panama; 1972.01.17 (JER) Compania Industrial y Financeria Mitu SA Panama; 1974.04.24 (JER) Co Me R Commerce des Metaux et de Representance SA Panama; 1974.10.18 (JER) IBP International Business Promotion SA Panama; 1976.01.16 (JER) Finroma Compania Financiera SA Panama; 1976.01.16 (JER) Lebene Compania Financiera SA Panama; 1976.02.02 (JER) SOPAGE SOCIEDAD PARA PARTICIPACION Y GESTION SA Panama; 1976.02.18 (JER) International Mangement’s Financial Sharing Corporation SA Panama; 1976.06.15 (JER) C L P Cement Lined Pipes SA Panama; 1976.07.20 (JER) Cantonal SA Panama; 1976.11.11 (JER) Nouba Investment SA Panama; 1976.11.26 (JER) IREC International Real Estate Corporation Panama; 1976.11.30 (JER) Bartabe SA Panama; 1977.01.04 (JER) Ecrimax SA Panama; 1977.09.07 (JER) Levante Securities Inc Panama; 1977.09.12 (JER) Sarria Finance SA Panama; 1978.02.21 (JER) FIS Investment Corporation Panama; 1978.02.24 (JER) IFC International Finance Corporation Panama; 1978.03.10 (JER) Societe Financiere St Germain SA Panama; 1978.05.16 (JER) Holding Castellana SA Panama; 1978.06.19 (JER) Societe Financiere de L’Esterel SA Panama; 1978.06.19 (JER) Tonfin SA Panama; 1978.11.29 (JER) Overseas Securities Inc SA Panama; 1978.12.12 (JER) Trifin SA Panama; 1978.12.26 (JER) Aiwal SA Panama; 1979.03.01 (JER) Financiera Florimont SA Panama; 1979.06.07 (JER) Holding Savona SA Panama; 1979.11.20 (JER) Financiera Mota SA Panama; 1980.04.29 (JER) Societe Financiere du Park SA Panama; 1980.05.07 (JER) Golden Arrow Corporation SA Panama; 1980.05.19 (JER) Societe Fiductaire San Pietro SA Panama; 1980.05.26 (JER) Tartana SA Panama; 1980.08.12 (JER) Maraica Foreign Investment Corporation SA Panama; 1980.10.01 (JER) Albany Overseas Corporation Panama; 1980.11.20 (JER) Habi Financial Management & Consulting Company ltd Inc Panama; 1981.02.20 (JER) Flager Inc Panama; 1981.07.20 (JER) Immobiliaria Boavista SA Panama; 1981.07.30 (JER) Laret Property Inc Panama; 1981.10.05 (JER) Societe Financiere Croix D’Or SA Panama; 1981.11.20 (JER) Euro American Holding for Overseas Investment Corporation Panama; 1982.01.25 (JER) Racardia Holding Inc Panama; 1982.05.27 (JER) Societe Financiere St Maurice SA Panama; 1982.08.12 (JER) Compagnie Financiere Colmar SA Panama; 1982.08.19 (JER) Compagnie Financiere Villenueve SA Panama; 1985.01.17 (JER) Blackpool Investment Inc Panama; 1985.02.07 (JER) Marshall Trading and Investment Inc Panama; 1985.02.07 (JER) Potomac International Corporation Panama; 1985.11.21 (JER) Futura Capital Corporation Panama; 1985.11.27 (JER) Societe Immobiliere Beausite SA Panama

[199] 2006.11.27 (JER) Titman in Interserv

[200] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2016/11/10/roberto-calvi-archiviata-ultima-inchiesta-sulla-morte-gip-assassinio-il-ruolo-di-vaticano-mafia-e-massoneria/3183527/

[201] Jacques de Saint Victor, “Patti scellerati: una storia politica delle mafie in Europa”, UTET, Torino 2013; https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2003/12/11/caso-calvi-vent-anni-fa-ho-mentito.html ; https://www.lastampa.it/cronaca/2016/11/19/news/caso-archiviato-l-omicidio-calvi-resta-un-mistero-1.34769399/

[202] https://opusdei.org/it-it/article/caso-calvi/

[203] https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1987/03/27/il-malinconico-tramonto-della-sogene.html

[204] Colloquio personale; 2001.10.25 (JER) Titman an Jermini

[205] 2006.11.27 (JER) Titman in Interserv

[206] (JER) Trial Eurafric, pages 3-5

[207] 1996.06.20 (JER) Wentworth, pages 1-7

[208] http://relevancy.bger.ch/php/clir/http/index.php?highlight_docid=cedh%3A%2F%2F20071213_35865_04%3Ait&lang=it&type=show_document

[209] https://www.suedostschweiz.ch/sport/fussball/2020-05-26/vor-25-jahren-warf-der-fc-lugano-inter-mailand-aus-dem-uefa-cup

[210] https://www.fclugano.com/grande-successo-della-festa-110/

[211] https://www.fclugano.com/storia/

[212] 1999.02.25 (JER) Fusi on FC Lugano

[213] 2002.09.24 (JER) Caso Bernardi

[214] 1996.06.20 (JER) Wentworth, pages 23-25

[215] 1996.06.20 (JER) Wentworth, page 4

[216] 1990.12.28 (JER) Promotion Investment Curaçao

[217] 1996.06.20 (JER) Wentworth, pages 7-9

[218] 2002.11.06 (JER) Caso Arint Bimini, pages 44-86

[219] 2001.10.25 (JER) Titman an Jermini

[220] https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/museum/exhibits/watergate_files/index.html ; https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000v4bn

[221] 2002.02.21 (JER) Titman on Jermini

[222] http://www.botta.ch/it/SPAZI%20DEL%20LAVORO?idx=20

[223] 2002.05.19 (JER) Fusi and Maurer on Jermini’s death; 2002.07.12 (JER) Della Pietra on Jermini’s death