In the world there are conflicts overshadowed by too many vested interests. Conflicts that turn the lives of tens of thousands of defenceless people upside down, but which no one tells about, because there are no good guys, only bad guys, everywhere. That of Cabinda is one of them: for more than half a century, in the general indifference of the media and the international community, a latent conflict has persisted here, in a small Angolan territory enclosed between Congo-Brazzaville and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is the richest area on the planet and, therefore, the most unfortunate.

A geographic anomaly, due to the choices of colonialism, and a geological anomaly: it is nicknamed the ‘African Kuwait’ because of its immense reserves of oil and other minerals, for which it has been the object of greed of regional and international powers since the 16th century[1]: this small territory (slightly larger than Palestine), home to only 800,000 inhabitants, is one of the richest territories on the continent[2]. Its Cabindan belong to the Bakongo ethnic group and speak Kikongo, the language of the Congolese Bantu, but the Angolans fight against this ethnic-cultural uniqueness, imposing Portuguese in schools[3]. The reason is clear: the enclave, rich in minerals such as manganese, titanium, potassium, gold, uranium and phosphates[4], supplies over 60% of Angola’s oil[5], or 80% of national exports[6]. Its 7,283 square kilometres, partly buried in the Mayombe forest and the marine subsoil, have enabled Angola to become one of the largest producers of black gold on the African continent[7]. Moreover, Cabinda is conveniently located for shipping, which made it a predestined victim as soon as Europeans discovered it.

The Republic of Cabinda

Cabinda in the 1960s[8]

Between 1600 and 1700, the Cabinda coastline was an important starting point for the African slave trade[9]. In the 19th century, the Franque clan usurped the power of the opposing clans (Nsambo, Npuna and Nkata Kolombo). The dominant figure, Francisco Franque, accumulated wealth through a close alliance with Brazilian slave traders and the European merchant navy, but his power waned with the end of the slave trade[10]. The Berlin Conference of 1884 took away the north shore of the Congo, until then one of Portugal’s main trading ports, granting Cabinda in exchange[11]. The following year, under Portuguese colonial rule, Portugal and the Franques signed the Treaty of Simulambuco[12]: Cabinda became a ‘protectorate’ with special privileges, while Angola became a full colony[13].

In 1956 oil was discovered: the Portuguese broke the Treaty of Simulambuco and made Cabinda a province of their Angolan colony[14]. When, in 1960, the hour of African independence sounded, Portugal remained deaf and insisted on controlling its own colonies (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Principe), resulting in nationalist wars in Cabinda as well[15]. In 1963, the three independence groups, the MLEC Movement for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda, the CAUNC Committee for Action and National Union of Cabinda and the Alliance of Mayombe[16] , united in the FLEC Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda[17] , led by Luis de Gonzaga Ranque Franque[18].

The FLEC fought for the independence of Cabinda, as a logical consequence of the Treaty of Simulambuco[19] , but the movement ended up getting involved in the Angolan civil wars[20]. In 1974, after the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon[21] , Portugal signed the Treaty of Alvor with the three main Angolan independence groups: the MPLA Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, the FNLA National Front for the Liberation of Angola and the UNITA National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, granting independence to the whole of Angola, including Cabinda[22].

Excluded from the negotiations, the FLEC declares the independence of the Republic of Cabinda on 1 August 1975, and forms a government in exile led by Henrique N’zita Tiago. Luis Ranque Franque is appointed president. After the Treaty of Alvor, MPLA troops, supported by Cuban military units from Congo Brazzaville, invade Cabinda, overthrow the provisional FLEC government and annex the province[23]. The MPLA creates a national oil company, Sonangol, to manage the flourishing oil industry. Sonangol’s revenues are used to finance the long struggle against UNITA, which instead finances itself with sales of diamonds and timber, as well as gifts from South Africa and the US government[24].

The African country fatally ends up in the crosshairs of the world’s great powers because of the wealth of its deposits, with the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in supporting the two opposing warring factions[25]. The Marxist-Leninist military junta that came to power, supported by the USSR and Cuba, favours the MPLA. In contrast, the rival FNLA and Unita movements[26] are supported by Mobutu’s Zaire (Congo DRC)[27] fighting for control of Cabinda[28] , the US, apartheid South Africa, the CIA and… Maoist China[29]. Angola is in a state of confusão: a Portuguese expression that renders well the idea of anarchy, neglect and confusion in which the country and its inhabitants find themselves[30].

December 1965: Cuban and MPLA soldiers in action in Cabinda as part of the so-called Operação Macaco, whose objective is the conquest of the Dembos province[31]

For the population it is a nightmare[32]. With the arrival of Gulf Oil, the enclave becomes the main source of income for the MPLA. One actor is still missing in this maelstrom: the French company Elf (now part of the colossus Total), well established in Congo Brazzaville, where it manages the Pointe Noire fields, adjacent to those of Cabinda. Elf is involved in various filth[33], and in this conflict supports the FLEC, led by José Auguste Tchioufou, an employee of Elf-Congo itself[34]. To avoid attacks on its installations and personnel, it also finances (and arms) UNITA[35].

In the end there will be Cuban soldiers defending an American oil multinational against auxiliaries armed by a French oil multinational[36]. In the 1990s, despite ceasefires and elections in 1992, fighting became fiercer than ever and more than a quarter of the population of Cabinda was forced to flee[37]. At the end of 2002, the armed conflict escalates, Luanda deploys 30,000 soldiers in Cabinda alone[38]. With the killing of UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi a cease-fire comes into effect, but the FLEC continues to fight, but is defeated by the MPLA[39].

The rebels’ armaments are outdated. They sporadically attack government troops deployed in Cabinda, as well as economic targets, including kidnapping foreign employees working in the oil, timber, gold mining and construction sectors. Their effectiveness is hindered by various factional splits, notably the division between FLEC-Renovada (FLEC-R)[40] , led by Antonio Bento-Bembe[41] , FLEC-FAC (Armed Forces of Cabinda)[42] , led by Henriques Tiago N’Zita: of Lindi ethnicity, he is another self-proclaimed president of Cabinda, in exile in Paris since 1991 and paid by Elf[43].

The third liberation front consists of a group called FDC, or Democratic Front for Cabinda. Clashes between the FDC and the other two factions of the FLEC take place over the control of gold deposits in the Buco Zau area of Cabinda[44]. In mid-2003, the Forças Armadas Angolanas (FAA) defeated the rebels and forced the group to sign a cease-fire – an agreement that was repeatedly violated by both sides. The FLEC still controls some areas of the Cabinda countryside and the conflict continues intermittently[45].

The attack on the Togo team

Attacks and kidnappings are FLEC militants’ response to the Angolan government[46]

The guerrillas gained international attention with an attack on Togo’s national football team in 2010[47]. Just a few months before the World Cup in South Africa, on 8 January, the Sparrowhawks, the name of the Togolese national team, are on a coach to Angola[48] for the African Cup of Nations[49]. The training camp is in Pointe Noir, Congo, about 100 km from where the matches were to be played, in the town of Cabinda[50]. The coach will never arrive: the attack, claimed by FLEC militiamen, kills the assistant coach, the spokesman and the driver[51], as well as injuring nine other people[52].

The Togolese have nothing to do with this affair, but the FLEC finds a way to rekindle attention around a conflict that has lasted for more than three decades amid general indifference[53]. The general secretary of the FLEC, Rodrigues Mingas, explains in a communiqué with regret that the target was not the Togolese team, but the Angolan escort[54]. From a media point of view, of course, this is a tremendous own goal. In 2016, the leader Henrique Tiago N’zita died[55]. The movement continues to exist. For its part, the Angolan army continues to pursue the fighters and is regularly accused of abuses and arbitrary detentions[56].

The disintegration of the movement into dozens of factions, sometimes rivals, sometimes allies, complicates any attempt at mediation. The bad faith of the Angolan regime, which has never really sought a negotiated solution, and the disinterest of the international community, undermine peace efforts[57]. In the course of military operations, serious and widespread human rights violations have been committed against the civilian population – with total impunity: executions, arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture and sexual violence[58]. People are convicted on the basis of confessions obtained under torture[59]. Both the FAA and the Angolan National Police (Polícia National – PN) do not really investigate. In some cases, they merely transfer the alleged perpetrators, including the officers and the unit of those responsible, to another province[60].

A few days after the 24 August 2022 elections, the Angolan government admitted that attacks were carried out not far from the Congolese border, in an area that serves as a rearguard base for independence fighters[61]. Since his election in 2017, President Joao Lourenço has the image of an open and moderate leader, but in Cabinda province, separatists accuse him of continuing the repressive policy of his predecessor José Eduardo Dos Santos[62]. Activists end up in prison where they suffer mistreatment and torture. Freedom of expression is denied to the Kabindians. For them, the right to demonstrate remains a mirage[63].

Resource exploitation and environmental disasters

The historical leader of FLEC, Henrique N’Zita Tiago[64]

The richness of Cabinda originated in the Mesozoic era, when the sinking of a portion of the earth’s crust in the South Atlantic produced fractures in the Cabinda sedimentary section[65]: during the early Cretaceous, in the drift phase, the African plates separated from the South American plates[66]. In the Congo River estuary and off the coast, within what is now the Block 0 oil concession, the rotation of faults creates traps that act as natural containers for several billion barrels of oil[67] and natural gas[68].

Oil is everywhere: the N’Sano field, located in Block 0, and the Greater Takula area, discovered in 1992, are two of the 21 fields allocated to Chevron, and is one of the largest oil and gas fields in the world[69]. The Takula Complex is located about 40 km from Malongo, in waters 50-75 metres deep, and produces about 200,000 barrels of oil per day[70]. The project is part of Cabinda Area A, within Block 0, and is operated by Chevron[71]. The company has signed a moratorium with the government to dump 12 million tonnes of hazardous oil residues into the ocean in the Cabinda Sea. Total and Esso immediately joined the request[72] – an agreement that remained in the shadows. Even more serious, Chevron is allowed to dump a short distance from the shore[73]. This means that oil-contaminated drill cuttings from many offshore oil platforms can be legally dumped into the ocean, posing a serious threat to the environment[74] for oil, chemical, sludge and metal wastes endanger marine life – and end up in the food web and on our plates.

Angola has to accept, it needs the money and infrastructure of big multinational companies[75]. The employees of these companies invade the Cabindese territory, but rarely come into contact with the local population: Chevron-Texaco has a blockhouse in Malonga[76] , a closed town, difficult for anyone to reach[77]. In contrast to the extreme poverty of Cabinda, Malonga is a real American city with electricity, running water, communication network, cinema, shopping areas and so on. It also has its own helicopter port from which oil workers are transported in and out of Cabinda.

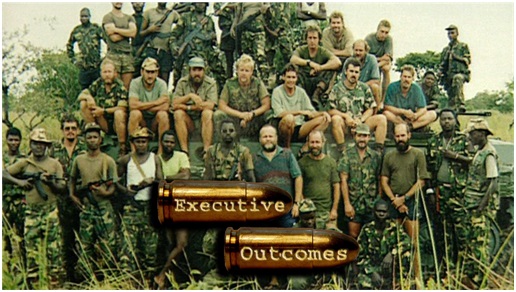

Chevron and other oil companies resort to using mercenaries for their private armies: they not only provide security for the workers, but also enable the companies to conquer territories where they usurp state power by force of arms. Until not so long ago, mercenaries in Cabinda were mainly recruited through Executive Outcomes[78], a South African company. When this fell into disgrace, the oil giants hired US army veterans. However, the Angolan government continues to use Executive Outcomes troops in the enclave as support for its national armed forces, the FAA[79].

The founder and chairman, Eeben Barlow[80], has made a strong impression on Russian military leaders. Convinced of his methods, they decided to replicate the South African company’s model with the paramilitary group Wagner[81], a nebulous network combining military force with commercial interests, the vanguard of Russia’s expanding ambitions in Africa. The private security company is headed by Yevgeny Viktorovich Prigozhin[82] , the tycoon known as ‘Putin’s cook’[83]. to whom the President has entrusted the defence of Russian interests in many African countries including Angola[84]. Interests ranging from gold mining concessions to diamond concessions. The Russian diamond company Alrosa is present in Angola and Zimbabwe and not out of solidarity with African producers[85].

South African mercenaries for the private armies of multinational mining companies[86]

Russia’s strategy is to win alliances by selling arms, with Algeria, Egypt and Angola among the biggest buyers. All this in exchange for concessions for the exploitation of natural resources, an option through which large companies such as Gazprom, Rostec, Lukoil, Lobaye and Invest Sarlu have obtained advantageous multi-year contracts[87]. And this is why, since 1955[88], Moscow has invested in the MPLA: Angola exports more than 800,000 of hydrocarbons per day – more than that supplied by Kuwait to the US[89]. The total value of the oil produced covers about 2/3 of the state’s total revenue[90].

Since Angola remained outside OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) until 2007, the country was not subject to restrictive quotas on its exports for many years. It also benefited from a combination of favourable geological conditions, a high exploration success rate and low operating costs[91]. In addition to Russia, ENI has also established many partnerships with oil companies in Cabinda, where it extracts fossil fuels with BP[92]: Created through a combination of the Angolan operations of BP and ENI, Azule Energy is the largest independent oil and gas producer in the country. The company holds 2 billion barrels of net resources and is growing to produce 250,000 barrels per day[93]. By 2026, it will be able to produce around 4 billion cubic metres of natural gas per year[94].

Azule Energy already has a strong portfolio of new projects for the coming years, including the Agogo Full Field project, located in Block 15/06, and the PAJ oil project, located in Block 31[95]. In the Ndungu field, located in Block 15/06, ENI made a major deepwater oil discovery. ENI owns 36.84% of it, in partnership with Sonangol (36.84%) and SSI Quinze (26.32%)[96]. People mistakenly think that colonialism is a legacy of the past: in reality, we continue to destroy large areas of foreign countries, causing environmental, economic and social disasters.

There are populations that have been waiting for years for reparations to which ENI is opposed. The commercial interests for the extraction of oil, diamonds, gold and uranium[97] prevail over the protection of the environment, besides endangering the health of the populations[98]. The intensive exploitation of African territory causes catastrophes that are soon forgotten or never disclosed – such as the spillage of tons of oil in the Niger delta by the ENI pipeline explosion in 2012[99]. But every foreign company has its own scandals: besides ENI, many other companies work in Cabinda. Among the main ones are ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, British Petroleum, Maersk, Total, Statoil, Petrogal, Petronas and Sinopec[100]. The Angolan flag carrier has agreements with the three oil companies working in Cabinda, even before independence from Portugal (1975)[101]: the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company, a joint venture run by Gulf Oil, Texaco and Petrofina[102]. All companies that obviously have a great influence not only on the economy, but also on the politics of a nation.

Yet there is a chronic problem of fuel shortages in Cabinda. Every day, citizens queue for hours at filling stations. The problem is smuggling by organised groups, and the authorities do little to curb this phenomenon[103]. Controls are crumbling, those who can take advantage of it, and this has not escaped the attention of the entourage of former president José Eduardo Dos Santos: like a good family man, he has placed his sons in the control room. The top management of Sonangol, the state oil company, was until recently occupied by his daughter, Isabel Dos Santos[104]. Listed by Forbes as the richest woman in Africa, Isabel has a myriad of interests in the diamond industry, banking, media, telecommunications and owns 7% of the Portuguese Galp Energia[105]. An arrest warrant has been issued against her by the national prosecutor’s office[106] for a number of offences, including money laundering and embezzlement[107].

Sonangol: the controversial Angolan oil company[108]

In 2012, the state declared its intention to build a deep-water port in Caio, north of the city of Cabinda, to free it from dependence on Pointe-Noire[109]. The contract was initially awarded, without a feasibility study or competition, to a company created only a few months earlier, the company Porto de Caio, SA. The owner of the company (with 99.9% of the shares) is Jean-Claude Bastos de Morais, a man known in Angolan circles as a special friend of the president’s son and his main business partner[110]. Porto de Caio is an ambitious project, and the cash of the Fundo Soberano de Angola (FSDEA), which invests in the port, is managed by Quantum Global, owned and controlled by Bastos de Morais[111], whose chairman of the board is José Filomeno dos Santos[112].

Four years after the announcement, the liquidity promised by Bastos is missing[113]. China comes forward, with the China Road and Bridge Company (CRBC)[114]. Angola is the main trading partner of the Chinese: development aid in exchange for fast lanes in industrial and mining concessions[115]. Beijing grants the loan to the Angolan State. The Angolan State hands it over to Porto de Caio. The Angolan Sovereign Fund, a state body, finances the remaining 15% that was to be provided by Porto de Caio: USD 124 million. Yet the Sovereign Fund had announced that its ‘investment’ in the project was $180 million. A difference of USD 56 million[116].

Oil is not the only resource in the small region[117]. Cabinda is the hub for many mining companies: Exploration Mining Resources, Ferrangol, Petril Phosphates, Minbos Resources, ITM Mining, Lumanhe, Axactor[118] and Endiama EP, the state-owned diamond company[119]. High-grade sedimentary marine phosphate deposits have emerged in the Cretaceous-Tertiary strata of the Cabinda district[120]. The phosphate serves the fertiliser industry, which is in great demand worldwide[121]. The ore was deposited in a marine basin covering a large part of the Cabinda district[122].

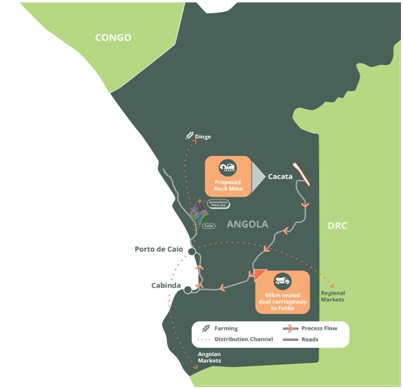

Minbos Resources Ltd.[123] an Australian company[124], in 2020 acquired a licence for the Cabinda Phosphate project[125] , developed by Minbos Resources (85%) with its local partner Soul Rock (15%)[126]. At the Cácata deposit, an open-pit mine, production is estimated at 150,000 tonnes by 2023, with prospects for expansion to 450,000 tonnes in the future[127]. The company considers it to be one of the last large sedimentary phosphate deposits in the world. The key to the deposit is its location, as transport costs are minimised. As phosphate is a bulk commodity, transportation is often the main cost of mining[128]. The phosphate rock market is worth billions of dollars. The impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a worldwide concern for farmers. The two warring countries supply 30% of international fertiliser, and Russia has suspended exports[129]. Cabinda fertiliser is crucial worldwide.

The Phosphate Cabinda project plans to exploit the Cácata deposit and deliver to Porto de Caio[130]

The other real wealth of the enclave is the diamonds in the north-eastern part of the region. There are many kimberlite deposits from which precious gems are extracted[131]: an industry worth USD 1.2 billion and ranking Angola fourth among world producers and second in Africa[132], with an estimated production of 9.3 million carats in 2021. However, about 60 per cent of the country’s mineral basins remain unexplored, opening up opportunities for further extraction[133]. By the end of 2023, the nation aims to become the largest producer of diamonds in the world[134].

The National Diamond Enterprise of Angola, a state agency, is responsible for approving concessions and licences. Sodiam is the commercial arm of Angola’s state-controlled diamond agency[135]. It ended up in the crosshairs of investigators for squandering public money to save a Swiss diamond company whose major shareholders are Sindika Dokolo, husband of Isabel Dos Santos, and Sodiam itself[136]. The sale of ‘blood diamonds’ allows rebel groups to finance civil wars and buy weapons. In Angola, Liberia, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo, since the 1990s, these groups have taken control of diamond mines with the complacency of the companies that exercise the global oligopoly of the trade in these gems[137].

Most diamonds, until the murder of its leader, Jonas Savimbi, were smuggled from UNITA-controlled regions[138]. Mining the diamonds in mines and alluvial deposits is the civilian population plundered from the villages and kept in slavery conditions. The minerals are entrusted to couriers who export them illegally to Namibia, ready to be mixed with legal stones and distributed in the markets until they reach Antwerp, considered the diamond processing capital of the world. The Belgian city then supplies jewellers around the world[139].

In 2015, journalist Rafael Marques de Morais was sentenced to six months in prison for naming army generals in a book revealing killings and torture in the country’s diamond fields[140]. The named generals are shareholders in the diamond company Sociedade Mineira do Cuango, which holds a concession in the Congo river basin, and in the company Teleservice: a consortium composed of Lumanhe, the company owned by the generals themselves, the state-owned diamond company Endiama, and ITM-Mining[141]. Teleservice is a private security company that monitors diamond mines and oil storage facilities in Soyo and Cabinda financed by former President Dos Santos who received the money through donations to his personal charitable foundation, Fundaçao Eduardo Dos Santos (FESA)[142].

Executives from Odebrecht, Dar Al-Handasah, Texaco, the Norwegian oil company Norsk Hydro, the Israeli security company Long Range Avionics Technologies and several executives from Sonangol were on the boards of FESA[143]. Today, reforms are taking place that push for more transparent contracting. In this context, in December 2021, the diamond company De Beers publicly announced its application to explore the north-eastern region of Angola[144].

The bloody diamond diggers[145]

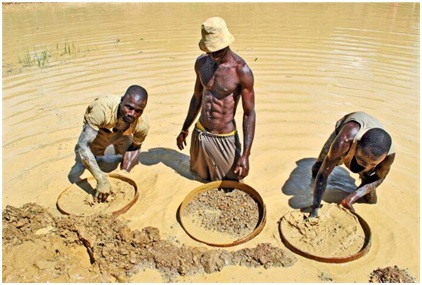

The same happens with gold. Every year, at least three tonnes of the precious mineral are illegally exported, mainly to Tanzania and the United Arab Emirates[146], so the state is trying to set up legal purchasing points in areas where it is mined[147]. The sites are located almost everywhere: in Buco-Zau, in the Belize municipality[148], in the southern province of Huila, in Mpopo and in the Chipindo area[149]: two contracts for a total of USD 10 million[150]. Buco Zau, about 120 kilometres north of Cabinda, is also important for palm oil production. In November 2009, the construction of a factory to process the product of existing plantations in the region was announced[151]. This factory will provide ENI with the raw material for the production of biofuels[152]. The joint venture between ENI and the state-owned company Sonangol for the development of the pilot project covers an area of 12,000 hectares of oil palm[153].

This is land recovered by deforestation. The mechanism of ‘land grabbing’, i.e. the reckless grabbing of land by multinational companies, is widespread throughout the region. In the province of Cabinda lies part of the Mayombe forest: the world’s second green lung. After the Amazon, the African forest is the largest on the planet with an area of 290,000 hectares spread over four states: Congo, Gabon, DR Congo and Angola[154]. In recent years, uncontrolled deforestation threatens to make it disappear. The problem with oil palms is their high demand for water and nutrients from the soil: growing in hot and humid places, the palms inevitably take away space from the rainforests[155].

In addition to the exploitation of workers, in palm plantations local communities denounce the direct link between the denial of access to land and the extreme poverty of the people[156]. In Cabinda, this means further violence, rape, constant harassment[157]. The colonial story that has left Africa as a patchwork of states designed for the administrative ease of the West rather than for legitimate ethnic ties, has generated separatist and irredentist tensions from Western Sahara to Namibia. When identities become complex and politicised by circumstance, and ‘rights’ to territory and governance become blurred, the basis for conflict is created[158], and Cabinda is a case in point: impossible to gain its independence, it is already almost impossible to fight for the war to end and the people to have a chance to be treated humanely.

What the international community is doing

Palm oil production kills orangutans, elephants and dozens of other animal species[159]

The local population does not benefit from the natural wealth of the province. The policies of the Angolan government have increased the suffering of the population and the inability to manage the many resources in the best possible way. There is no project to improve life and bring peace. There is no high school, no technical-professional training institute in Cabinda[160]. The cost in human lives goes far beyond the estimated 500,000 victims of the civil war: 30% of children die before the age of five and the average life expectancy is only 45 years[161]. The unemployment rate is 88% and the only existing infrastructure dates back to colonial times[162].

In the search for a solution to the conflict, international involvement is totally absent, even that of the United Nations and pan-African bodies. Actors from Portugal, South Korea, Gabon, Namibia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the United States including the church have tried to offer mediation support, but the Angolan government has refused such offers, as it has always wanted full control[163]. Its remedy is repression. There is a need to convince the parties to return to the negotiating tables for a mutually beneficial agreement, but the reality is that it suits no one, especially the global arms industry, for this to happen. As is often the case, economic interests come before any other consideration.

That is why we write. So that it will be known. Because no one has the right to deny and erase the history of a people and a land. A people without history is a people without a soul, and for the people of Cabinda, the richest land on the planet, the soul is a luxury no one can afford[164].

[1] https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/etudes-de-lifri/histoire-dune-guerilla-fantome-fronts-de-liberation-de-lenclave-cabinda

[2] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083 pag. 2

[3] https://lospiegone.com/2020/08/30/ricorda-2010-flec-la-voce-di-cabinda/

[4] https://www.hauniversity.org/en/Angola-Cabinda.shtml

[5] https://africaexpress.corriere.it/2010/09/05/angolagli_indipendentisti_di_c/

[6] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[7] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[8] http://fotoscabinda.blogspot.com/2009/10/cabinda-antiga-2.html

[9] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000121577 pag. 556

[10] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/abs/family-strategies-in-nineteenthcentury-cabinda/1F14475C972D2235BA8E9A7A717D9321

[11] http://www.cabinda.org/histoireang.htm

[12] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/abs/family-strategies-in-nineteenthcentury-cabinda/1F14475C972D2235BA8E9A7A717D9321

[13] Daniel Dos Santos, “Cabinda: The Politics of Oil in Angola’s Enclave,” in AfricanIslands and Enclaves ed. Robin Cohen (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1983), 102

[14] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083

[15] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[16] http://www.commission-refugies.fr/IMG/pdf/Angola_-_les_independantistes_dans_l_impasse_au_Cabinda.pdf pag. 5

[17] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083

[18] https://www.altoconselhodecabinda.org/en/2772-2/

[19] https://www.macaubusiness.com/angola-cabinda-independence-fighters-claim-18-government-soldiers-killed/

[20] https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/etudes-de-lifri/histoire-dune-guerilla-fantome-fronts-de-liberation-de-lenclave-cabinda

[21] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[22] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083

[23] https://africaexpress.corriere.it/2010/09/05/angolagli_indipendentisti_di_c/

[24] https://www.icij.org/investigations/makingkilling/greasing-skids-corruption/

[25] https://www.riccardomichelucci.it/tag/guerra-fredda/

[26] http://www.commission-refugies.fr/IMG/pdf/Angola_-_les_independantistes_dans_l_impasse_au_Cabinda.pdf pag. 5

[27] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[28] https://www.cmi.no/publications/7719-cabinda-separatism

[29] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[30] https://birdmenmagazine.com/2019/07/18/ancora-un-giorno-storia-di-guerra-e-di-vita/

[31] https://www.tchiweka.org/fotografia/1010003034

[32] https://www.riccardomichelucci.it/tag/guerra-fredda/

[33] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[34] http://www.commission-refugies.fr/IMG/pdf/Angola_-_les_independantistes_dans_l_impasse_au_Cabinda.pdf pag. 6

[35] https://www.icij.org/investigations/makingkilling/field-marshal/

[36] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[37] Minorities at Risk, “Chronology for Cabinda in Angola”, http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/mar/chronology.asp?groupId=54003

[38] https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/Angola%20Between%20War%20and%20Peace%20in%20Cabinda.pdf

[39] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083 pag. 39

[40] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[41] https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Workshop/kone98.html

[42] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[43] http://www.commission-refugies.fr/IMG/pdf/Angola_-_les_independantistes_dans_l_impasse_au_Cabinda.pdf pag. 9

[44] https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Workshop/kone98.html

[45] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083

[46] https://www.icij.org/investigations/luanda-leaks/from-colonization-to-kleptocracy-a-history-of-angola/

[47] https://www.cmi.no/publications/7719-cabinda-separatism

[48] https://lospiegone.com/2020/08/30/ricorda-2010-flec-la-voce-di-cabinda/

[49] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[50] https://lospiegone.com/2020/08/30/ricorda-2010-flec-la-voce-di-cabinda/

[51] https://www.corriere.it/esteri/10_gennaio_10/cabinda-intervista-ministro-esilio-massimo-alberizzi_441b6e74-fdcb-11de-b65b-00144f02aabe.shtml

[52] https://africaexpress.corriere.it/2010/09/05/angolagli_indipendentisti_di_c/

[53] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[54] https://www.corriere.it/esteri/10_gennaio_10/cabinda-intervista-ministro-esilio-massimo-alberizzi_441b6e74-fdcb-11de-b65b-00144f02aabe.shtml

[55] https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/etudes-de-lifri/histoire-dune-guerilla-fantome-fronts-de-liberation-de-lenclave-cabinda

[56] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[57] https://www.ifri.org/fr/publications/etudes-de-lifri/histoire-dune-guerilla-fantome-fronts-de-liberation-de-lenclave-cabinda

[58] https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/Angola%20Between%20War%20and%20Peace%20in%20Cabinda.pdf

[59] https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLJ666347

[60] https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/Angola%20Between%20War%20and%20Peace%20in%20Cabinda.pdf

[61] https://www.theafricareport.com/223707/angola-cabinda-an-unsolvable-problem/

[62] https://www.francetvinfo.fr/monde/afrique/politique-africaine/angola-les-velleites-d-independance-de-la-province-petroliere-du-cabinda_3449219.html

[63] https://www.francetvinfo.fr/monde/afrique/politique-africaine/angola-les-velleites-d-independance-de-la-province-petroliere-du-cabinda_3449219.html

[64] https://africaexpress.corriere.it/2010/09/05/angolagli_indipendentisti_di_c/

[65] https://archives.datapages.com/data/specpubs/history2/data/a110/a110/0001/0000/0005.htm

[66] https://www.grin.com/document/270708

[67] https://library.seg.org/doi/full/10.1190/1.1523746

[68] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[69] https://ejatlas.org/conflict/angola-cabinda/?translate=it

[70] https://www.searchanddiscovery.com/abstracts/html/1990/norway/abstracts/1515b.htm

[71] https://www-woodmac-com.translate.goog/reports/upstream-oil-and-gas-cabinda-a-takula-complex-14320063/?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=it&_x_tr_hl=it&_x_tr_pto=sc

[72] https://www.nigrizia.it/notizia/angola-il-governo-autorizza-chevron-a-inquinare

[73] https://www.corriere.it/esteri/22_agosto_19/patto-l-angola-chevron-scaricare-mare-veleni-petrolio-c20e3410-1ff5-11ed-b2f1-72942e0bd969.shtml?refresh_ce

[74] https://www.club-k.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=48797:residuos-petrolifero-descarregados-nos-mares-de-angola-ameacam-ambientes-marinhos&catid=2&Itemid=1069&lang=pt

[75] https://www.corriere.it/esteri/22_agosto_19/patto-l-angola-chevron-scaricare-mare-veleni-petrolio-c20e3410-1ff5-11ed-b2f1-72942e0bd969.shtml?refresh_ce

[76] https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Workshop/kone98.html

[77] https://www.latlong.net/place/malongo-angola-2695.html

[78] https://www.executiveoutcomes.com/

[79] https://www.africa.upenn.edu/Workshop/kone98.html

[80] SOLDATI DI SVENTURA: LA MINACCIA GLOBALE DELL’INDUSTRIA PRIVATA DELLA MORTE | IBI World Italia

[81] WAGNER GROUP: I FANTASMI DI MORTE SCATENATI DAL CREMLINO | IBI World Italia ; LIBIA: LA LOTTA PER IL PETROLIO | IBI World Italia ; MINSK, DUE ANNI DOPO: IL LUTTO SENZA SPERANZA | IBI World Italia

[82] https://www.theafricareport.com/16511/russias-murky-business-dealings-in-the-central-african-republic/

[83] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2022/07/05/il-gruppo-wagner-e-i-mercenari-in-africa-dove-e-come-la-russia-trova-loro-per-finanziare-la-guerra-in-ucraina-e-arginare-le-sanzioni/6649307/

[84] https://www.theafricareport.com/16511/russias-murky-business-dealings-in-the-central-african-republic/

[85] https://greenreport.it/risorse/le-mani-della-russia-sui-diamanti-della-repubblica-centrafricana/

[86] https://www.journeyman.tv/film/6448/executive-outcomes

[87] https://www.med-or.org/news/il-ritorno-della-russia-nel-corno-dafrica

[88] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[89] https://ejatlas.org/conflict/angola-cabinda/?translate=it

[90] https://journals.openedition.org/mulemba/416 nota 61

[91] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[92] https://www.editorialedomani.it/angola-mozambico-congo-algeria-la-corsa-al-gas-prepara-le-crisi-di-domani-x0whmasc

[93] https://www.hartenergy.com/exclusives/bp-eni-jv-begins-operations-angola-201454

[94] https://www.nigrizia.it/notizia/angola-eni-chevron-bp-e-total-investono-sul-gas

[95] https://www.hartenergy.com/exclusives/bp-eni-jv-begins-operations-angola-201454

[96] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/04/12/eni-raises-angola-ndungu-field-estimate-to-1b-barrels/

[97] https://africaexpress.corriere.it/2010/09/05/angolagli_indipendentisti_di_c/

[98] https://www.berggorilla.org/en/gorillas/countries/artikel-countries/the-struggle-for-survival-in-the-maiombe-forest-continues/

[99] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2018/01/09/risarcimento-per-il-disastro-ambientale-in-nigeria-eni-sara-giudicata-in-italia-prima-vittoria-della-comunita-ikebiri/4082340/#:~:text=In%20Burundi%20%C3%A8%20stata%20calcolata,non%20verr%C3%A0%20pi%C3%B9%20prodotto%20cibo.

[100] https://www.analisidifesa.it/2016/06/angola-un-gigante-che-barcolla/

[101] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[102] https://ejatlas.org/conflict/angola-cabinda/?translate=it

[103] https://novojornal.co.ao/sociedade/interior/contrabando-de-combustivel-em-cabinda-preocupa-cidadaos-ha-escassez-em-quase-todos-os-postos-de-abastecimento-da-provincia-110048.html

[104] Microsoft Word – Angola Report 13. Draft.doc (ibiworld.eu)

[105] https://www.analisidifesa.it/2016/06/angola-un-gigante-che-barcolla/

[106] https://www.africarivista.it/angola-ordinato-larresto-di-isabel-dos-santos/209835/

[107] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-51218501

[108] https://www.icij.org/investigations/luanda-leaks/switzerland-freezes-angolan-tycoons-900-million-fortune/

[109] https://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/5130/The_Atlantic_ports_puzzle

[110] https://www.makaangola.org/2017/03/stealing-with-presidential-decrees/

[111] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/07/angola-sovereign-wealth-fund-jean-claude-bastos-de-morais-paradise-papers

[112] https://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=255101409

[113] https://www.makaangola.org/2017/03/stealing-with-presidential-decrees/

[114] https://constructionreviewonline.com/news/construction-works-at-caio-deep-water-port-in-angola-to-resume/

[115] https://www.analisidifesa.it/2016/06/angola-un-gigante-che-barcolla/

[116] https://www.makaangola.org/2017/03/stealing-with-presidential-decrees/

[117] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2019/04/16/ancora-un-giorno-il-vibrante-e-avvincente-racconto-per-immagini-del-reportage-di-kapuscinski-in-angola/5112814/

[118] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/04/18/why-angola-is-africas-next-mining-powerhouse/

[119] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/11/18/positioning-angola-as-a-globally-competitive-mineral-producer/

[120] https://www.worldcat.org/it/title/8554235919

[121] https://irpimedia.irpi.eu/paradossi-delle-sanzioni-dentro-la-filiera-del-fosfato-dalla-siria-alleuropa/

[122] https://www.worldcat.org/it/title/8554235919

[123] https://minbos.com/cabinda-phosphate-project/

[124] https://www.worldcat.org/it/title/5866483439

[125] https://energycapitalpower.com/biggest-mines-in-angola-by-production/

[126] https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/cabinda-phosphate-project/

[127] https://energycapitalpower.com/biggest-mines-in-angola-by-production/

[128] https://www.worldcat.org/it/title/5866483439

[129] https://www.freshplaza.it/article/9407626/la-perdita-dei-fertilizzanti-russi-e-un-inconveniente-per-il-sudafrica/

[130] https://minbos.com/cabinda-phosphate-project/

[131] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[132] https://energycapitalpower.com/biggest-mines-in-angola-by-production/

[133] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/11/18/positioning-angola-as-a-globally-competitive-mineral-producer/

[134] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/04/18/why-angola-is-africas-next-mining-powerhouse/

[135] https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[136] https://www.icij.org/investigations/luanda-leaks/angolan-investment-at-risk-as-dos-santos-linked-jeweler-goes-under/

[137] https://www.amnesty.ch/it/news/2007/i-diamanti-della-guerra-costano-vite-umane

[138] https://www.opiniojuris.it/i-diamanti-insanguinati-sono-ancora-attuali/ ; https://www.britannica.com/place/Angola/Resources-and-power

[139] https://www.opiniojuris.it/i-diamanti-insanguinati-sono-ancora-attuali/

[140] https://www.opiniojuris.it/i-diamanti-insanguinati-sono-ancora-attuali/

[141] https://www.makaangola.org/2013/07/generals-chase-journalist-over-blood-diamonds-investigation/

[142] https://www.icij.org/investigations/makingkilling/greasing-skids-corruption/

[143] https://www.icij.org/investigations/makingkilling/greasing-skids-corruption/

[144] https://furtherafrica.com/2022/11/18/positioning-angola-as-a-globally-competitive-mineral-producer/

[145] https://www.opiniojuris.it/i-diamanti-insanguinati-sono-ancora-attuali/

[146] https://furtherafrica.com/2017/04/14/three-tons-of-gold-illegally-exported-from-angola/

[147] https://www.infomercatiesteri.it/highlights_dettagli.php?id_highlights=8489#

[148] https://african.business/2021/12/energy-resources/angolas-buried-treasures-why-investors-see-long-term-potential-in-the-countrys-mining-sector/

[149] https://www.infomercatiesteri.it/highlights_dettagli.php?id_highlights=8489#

[150] https://furtherafrica.com/2018/01/08/angola-mining-companies-to-invest-us10m-for-gold-exploration/

[151] https://oilpalminafrica.wordpress.com/2010/08/19/angola/https://www.wrm.org.uy//wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Oil_Palm_in_Africa_2013.pdf pag. 21;

[152] https://www.wrm.org.uy//wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Oil_Palm_in_Africa_2013.pdf pag. 13

[153] https://www.wrm.org.uy//wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Oil_Palm_in_Africa_2013.pdf pag. 13

[154] http://expoangolait.blogspot.com/2015/09/la-foresta-di-mayombe-il-secondo.html

[155] https://greenmarketing.agency/olio-di-palma-ambiente-e-deforestazione/

[156] https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/idee/congo-olio-di-palma-e-colonialismo/

[157] https://www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-analyse-1048_fr.html

[158] https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/cria/article/view/104/1083 pag. 2

[159] https://greenmarketing.agency/olio-di-palma-ambiente-e-deforestazione/

[160] https://www.club-k.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=48872:analista-preve-desafios-importantes-para-a-nova-governadora-de-cabinda-mara-quiosa&catid=14&Itemid=1090&lang=pt

[161] https://www.icij.org/investigations/makingkilling/greasing-skids-corruption/

[162] https://lindro.it/cabinda-la-spina-al-fianco-dellangola-lourenco-come-dos-santos/

[163] https://www.hrw.org/legacy/backgrounder/africa/angola/2004/1204/10.htm

Excellent, thorough and fair. Well done.