Art began as the personal pleasure of its creator, from the Neanderthal caves onwards. It has been refined, it has changed, it has become a symbol of beauty, it has been purchased to show off one’s home, one’s life, one’s social status. All this has remained, of course, but the quantitative explosion of art objects, as well as the increasing value of antique objects, has perverted this perception as well, transforming an object, first considered artistic, into an economic value, comparable to that of a currency or metal.

Everything that can be monetised is monetised. Everything that is assessable and transferable becomes speculation, a safe haven, an investment. The symbol of this perversion is the Freeport – an extra-customs, closed and secret zone where art objects can be used to launder money, to buy and sell weapons, drugs or slaves, and who knows what else. This is not easy moralising. Things happen because there are chains of cause and effect, and it is difficult to oppose them. So it can happen that, in the deep forest of Thuringia, one of the most beautiful, poorest and least inhabited areas of Germany, an ancient villa of the princes of Saxony ends up being the place where, secretly, paintings and statues are used for trades that it is better that no one discovers.

Public opinion, however, is overwhelmed by a thousand other difficulties, and in the end it doesn’t give a damn about some crazy billionaire who pays exorbitant sums of money for a painting he can’t even stick on the wall and look at, because he has to hide it from thieves and tax collectors. That is why we feel it is right to write this story, at least from a testimonial point of view, so that it will not be forgotten.

What are Freeports

The wonderful Piazza dell’Unità in Trieste, Freeport since 1719[1]

Freeports originated at the same time as the institution of customs duties at the border between two states: they are places to store goods in transit, without having to pay customs: in the 16th century, Livorno, Genoa and other Italian cities were famous for offering special economic zones in which to stow goods. By the 18th century, the phenomenon had spread throughout Europe[2]. Since then it has become customary, especially after the discovery of America and the beginning of the colonisation of Africa and Asia, to use these Freeports to hide stolen goods. Things changed after the French Revolution (1789) and the Congress of Vienna (1815), when wealthy families on the run, or soldiers returning home with booty in their saddle, became an economic factor that changed the history of some cities and some families – especially on the shores of the oceans and, in Europe, along the navigable course of the Rhine[3].

Over the next two centuries, especially during the Second World War, when tax havens had sprung up and belligerent nations were trying to disguise their trade in raw materials and industrial artefacts, the Freeport concept became a cornerstone of the world trading system, but also a phenomenon combated, more or less resolutely, by nation states – with the emergence of the concept of smuggling and the laundering of illegal proceeds[4]. The fight against illegal transnational trade and, later, the concealment of illicit financial assets, was at the origin of the birth of Interpol, the Egmont Group[5] and various other police instruments and state investigative agencies that, over the last 90 years, have fought this phenomenon with varying fortunes – and inconstant diligence.

Since the establishment of Interhandel AG Basel (the financial holding company that concealed the financial and industrial investments of National Socialism abroad[6]), Switzerland has specialised in the storage of sensitive goods (gold, precious metals, works of art, weapons, drugs bearer bonds) and became the first global Freeport – suffice it to say that, in the three freeports at Zurich airport (Philoro, Embrach and Safeguard), customers have over half a million square metres of numbered cells, almost inaccessible to the judicial authorities, capable of maintaining the required humidity and temperature for centuries[7]. The first of these companies, the German company Philoro, allows not only the interchange between different Freeports located in different European cities, but even the marketing of products located in virtual Freeports – i.e. hidden where really no one could ever discover and control them, yet legalised in order to be traded[8].

Following an endless series of banking and organised crime scandals, Switzerland has been confronted over the decades – on the one hand – by the fact that other countries demand transparency and traceability for criminal operations and – on the other – by the fact that, worldwide, competition in the illegal market has grown to once unthinkable levels[9]. In 2017, Berne introduced the CRS (Common Reporting Standard), pledging to exchange information with partner countries on foreigners holding bank accounts in the country, as part of its efforts to crack down on tax evasion and fraud[10]; at the same time, being under just as much international pressure, countries such as Luxembourg report the active interests of those who want to save on taxes in their home country. The real estate market, a century ago the easiest way to move money and goods, is now completely controlled. All this opens up a new slice of the market: that of works of art, which in recent years has become an efficient way of investing large amounts of money discreetly[11].

Behind this lucrative business lie, essentially, two reasons: the first is that works of art are assets whose value cannot be precisely quantified[12] and is little affected by the instability of the financial markets. The second is regulatory: few markets are as poorly regulated as this one, making works of art an excellent tool for tax evasion and money laundering[13]: it is the only ‘financial market’ not subject to the world’s Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). This means that wherever works are stored, anti-money laundering regulations are not legally binding, but at most have the value of a recommendation[14].

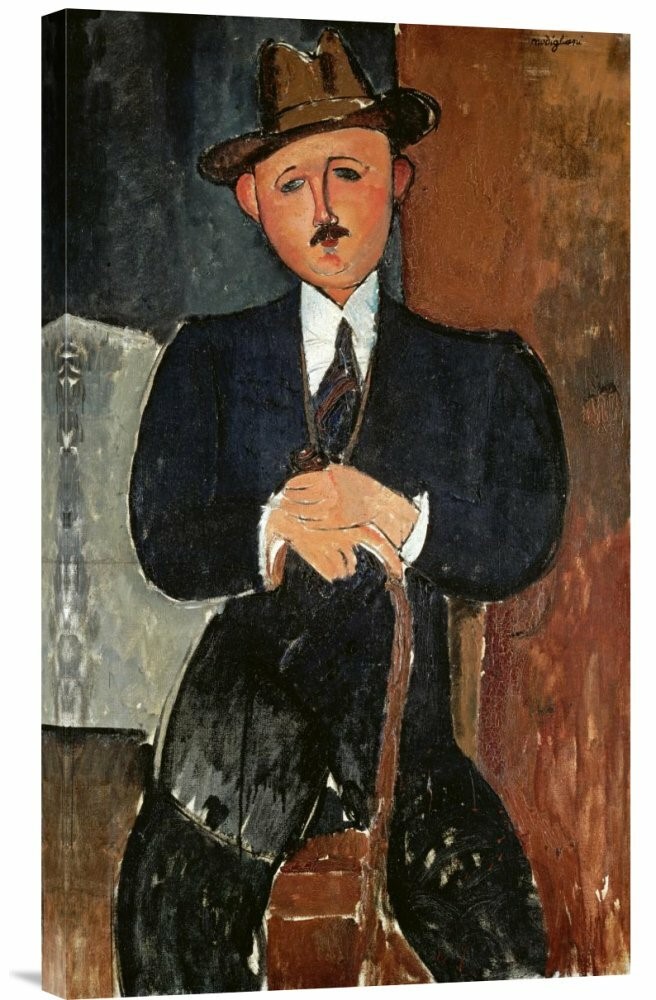

Modigliani’s painting (Seat man with a cane) recycled by art dealers after disappearing during World War II[15]

The problem of art laundering is well-known: at the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos, economist Nouriel Roubini explained: ‘Whether we like it or not, art is used for tax avoidance and evasion. It can be used for money laundering. You can buy something for half a million, not show a passport and send it off. A lot of people use it to launder”[16]. There are dozens of examples: from Edemar Cid Ferreira, the former Brazilian banker who laundered millions of dollars through a collection of 12,000 paintings and statues[17], to the Nahmad family of gallerists, who own the company International Art Center SA Panama[18], owner of a Modigliani painting (‘Seated Man with a Cane’), which reappeared at a Christie’s auction after being stolen by the Nazis during the occupation of Paris[19]; recently, some cases have been uncovered thanks to the publication of the Panama Papers[20].

In this context, the natural – and often final – destination of many works of art are the Freeports (Zollfreilager in German, Entrepôt in French), huge high-security warehouses that allow individuals and companies (often based in tax havens) to store valuables in an easy-to-reach place and use them as currency of exchange, without controls and without taxes[21]. Assets stay there for years: analyst Walter Leonhardt points out that the easiest way to launder money through Freeports is to store expensive works for five years. Because at the sixth year, the statute of limitations for money laundering as a criminal offence (in the US[22] and Germany[23]; in Switzerland the term is ten years[24], in the UK there is no statute of limitations for this offence[25]); then the owners can legally resell the artwork or fake a transaction by selling to another offshore company of the same owner[26].

Spread all over the world, these tiny tax havens house very valuable assets that the owners can secretly admire forever (there are special showrooms), waiting to sell them anonymously to a buyer who will most likely leave the works where they are, waiting to start the tour again[27]. The core of this activity is the impenetrable secrecy of the Freeports, without breaking any laws: no one can say whether the works in one of these warehouses have been stolen, bought with the proceeds of illegal activities or are the result of a legal investment. This secrecy, combined with the unregulated nature of the market, makes it very difficult to link owners and works stored in Freeports, as no government can regulate, tax or investigate property stored within a secret, extraterritorial jurisdiction[28].

The tip of the iceberg: Yves Bouvier and Giacomo Medici

The Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier[29]

The unscrupulous Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier is the owner of the family business Natural Le Coultre SA[30], a 100-year-old Geneva-based shipping company which, under his control, specialises in the storage, warehousing and shipping of works of art[31]. Most of the storage is in the secret warehouses of the Freeport in Geneva, the largest repository of works of art in the world: 2300 have since been exhibited in the British Museum, 200,000 have been placed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York[32]. There are an estimated 1.2 million works of art in the Swiss warehouse, including a collection of 1000 Picassos[33].

Its warehouse buildings occupy a space equivalent to twenty-two football pitches; the owner of the majority stake in Geneva Freeport is the canton of Geneva, while Yves Bouvier is the largest private shareholder[34], holding 5% of the property until 2017 (the year in which he sold Natural Le Coultre[35]); at which point, under pressure from the Swiss authorities, Bouvier moved: in 2010 to Singapore, in 2014 to Luxembourg and then to Shanghai[36], through Euro Asia Investment SA Luxembourg, owned by Bouvier[37]. In addition to the secrecy and economic advantages, the landing of works at a modern Freeport allows gallery owners, collectors and art dealers to store works in extremely secure, fireproof premises, where space is never in short supply and where temperature and humidity are controlled, protected from sunlight[38].

The enormous fortune Bouvier amassed could not, however, have provided him, on its own, with the resources to construct such expensive buildings as the warehouses he built; in fact, Bouvier owes his fortune to his unscrupulous activity as an intermediary on behalf of the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev: the tycoon built his fortune with Uralkali, Russia’s largest potash fertiliser company – of which he controlled the majority stake until 2010, when he was forced to sell to Suleyman Kerimov, Alexander Nesis and Filaret Galchev[39], entrepreneurs very close to Vladimir Putin[40]. In little more than ten years, Bouvier enabled Rybolovlev to acquire one of the most important private collections in the world, including works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Mark Rothko, among others[41].

From 2003 to 2014, the Swiss dealer bought paintings by Van Gogh, Modigliani and Klimt, then resold them to the Russian businessman at such inflated prices as to generate staggering profits: when, in 2014, Rybolovlev realised he had been swindled and filed a lawsuit against Bouvier, he claimed that the latter’s earnings from the purchase of the 38 works bought over the years amounted to one billion dollars[42]. Clamorous is the case of the ‘Salvator Mundi’, a work attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that Bouvier, paid by Rybolovlev in 2013 with a commission of 2%, was bought by Bouvier for $80 million and transferred to the Russian oligarch for $127 million[43]; on 15 November 2017, the painting was resold by Rybolovlev at a Christie’s auction for a record $450.3 million[44]. The buyer is Saudi Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud[45].

In December 2014, Rybolovlev’s accidental discovery of the sale price of Modigliani’s painting ‘Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu’, procured for him by his intermediary years earlier, caused the case to explode: sold by the former owner for USD 93.5 million, ‘Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu’ was bought by the Russian for USD 118 million[46]. Bouvier owns some 150 companies, such as Diva Fine Arts SA Panama and Diva Fine Arts Inc. Tortola (Virgin Islands), which are used to move huge sums of money, untraceable by the Swiss authorities; as a resident of Singapore, Bouvier avoids declaring to the Swiss government the amount of transactions concluded with Rybolovlev, and is therefore only liable for those completed while he was still a Swiss citizen (until 2009)[47].

The ‘Crater of Euphronius’, an Athenian vase over 2500 years old[48]

In September 2021, Yves Bouvier was acquitted by a Geneva court of the charges of fraud, mismanagement, breach of trust and money laundering[49], but his reputation was destroyed[50], so much so that he asked Rybolovlev for USD 1 billion in compensation[51]. The consequence of the Bouvier Affaire is the great attention that the international media are beginning to devote to the tendency of the richest people on the planet to invest in the art market in order to conceal or increase their wealth[52], or to hide the proceeds of criminal activities[53].

The Bouvier case is not the first to directly involve the Freeports business. The Italian antiquarian dealer Giacomo Medici, active in Rome since the 1960s, was first convicted in 1967 for buying stolen archaeological artefacts – a conviction that made him famous and convinced the US billionaire Robert Hecht to choose him as an intermediary[54]: from Medici he supposedly bought in 1972 the Crater of Euphronius, a vase made in Athens around 500 BC, and then sold it to the Metropolitan Museum in New York; although the exact provenance of the artefact has never been established, it is estimated in court that it was stolen in 1971 by grave robbers in the Etruscan cemetery of Cerveteri, and then sold to Medici[55]. In 2008, the Metropolitan returned the work to Italy[56].

Certifying the illicit provenance of the Crater are photographs found by carabinieri during a raid carried out in September 1995 at Medici’s warehouse in Geneva’s Freeport: the operation, carried out in agreement with the Swiss police, arose from an auction catalogue of Sotheby’s, in which a sarcophagus was put up for sale which the Italian military recognised as having been stolen from the church of San Saba in Rome[57]; tracing, thanks to the collaboration of the auction house, Medici’s name as the owner of the auctioned property, the carabinieri reconstructed the man’s role and network of international accomplices: During the raid on the warehouse of the Geneva Freeport, five rooms totalling 200 square metres[58], a restoration workshop and a showroom were found[59].

In January 1997, Medici is arrested and his Geneva warehouse is opened for inventory[60]. The final report, presented in July 1999, mentions 3800 objects, more than 4000 photographs of artefacts and 35,000 documents containing information on the goods’ trade[61]. Two of those photographs, dated May 1987, show Medici and Hecht next to the Euphronios Crater[62]. In 2005, Medici was sentenced to ten years imprisonment (later reduced to eight in 2009) and to pay a fine of EUR 10 million[63]. The case created such a stir that in 2009, the Confederation was persuaded to bring its customs legislation into line with European standards: since then, the Geneva Freeport is no longer considered an extra-territorial zone, so some services on site are now subject to Swiss VAT (7.6%), however this does not apply to the value of the stored objects, storage fees and insurance premiums. In addition, all stored items must be recorded in an inventory with the description, value, size, date and place of storage, country of origin and the name and address of the person who has the item – all directly in the Customs database[64].

The mystery of the Meiningen Freeport

The huge Freeport of Meiningen in the Thuringian Forest[65]

These measures do not affect the Freeports business in the slightest. In 2016, a priceless collection was discovered in the Geneva warehouse: 45 crates containing Roman and Etruscan antiquities, belonging to a convicted criminal, the British art dealer Robert Symes[66]. The treasure, including two Etruscan sarcophagi in excellent condition, had been in the warehouse for over fifteen years and was found in boxes labelled with the name of an off-shore company belonging to Symes[67]. This scandal erupts as Swiss lawmakers discuss stricter regulations for Freeports and bonded warehouses. As of 1 January 2016, the Federal Customs Administration (EZV) acquires new powers to control the entry and exit of goods: the government introduces a six-month time limit for the storage of goods intended for export; exporters must explicitly declare whether the goods are intended for export; in addition, the identity of the buyer must be declared[68].

While the new rules on the sale of works of art use due diligence and financial intermediaries to improve transparency, the amendments to the Customs Act aim to reduce the secrecy of the art market by encouraging a higher turnover rate of goods. Renters will have less freedom to keep artworks indefinitely, or at least face more administrative hurdles to do so. Consequently, fences will have fewer opportunities to hide illegally obtained objects from customs authorities[69].

The weak point: the anonymity of honest dealers might be compromised by the obligation to list the actual owners in the inventory[70]. In addition, the rules could dissuade investors from operating in Switzerland. The country’s art market, which revolves around major events such as Art Basel, could suffer from a potential haemorrhaging of customers to Freeports located in more legislatively attractive areas, such as Luxembourg, Monaco, Singapore[71] (whose warehouses are controlled by Swiss shareholders[72]), and Delaware[73].

In the city of Meiningen, Thuringia, Viktor Schulte and Nicolas Perren’s Vallor Development GmbH is converting a Bundesbank building to house works of art and other luxury goods in its 4,000 square metres[74]; there is also a duty-free safe inside the building[75]. The company was founded in 2018 with a capital of only €25,000, half of which was paid by Schulte, the other half by Meta Holding GmbH Davos (Switzerland)[76], which at the time of foundation had a capital of CHF 2,000, now increased to CHF 20,000, of which Perrin controls the majority, while the minority share belongs to architect Peter Bitschin[77]. Vallor is part of a group of companies, the most important of which is Zentraldepot AG Berlin – which is then the company that runs the art trade in Meiningen, and whose profits are reinvested by Vallor Assets GmbH Berlin[78].

To improve its image, Vallor Development is building 96 flats for pensioners[79]. Although Vallor’s is billed as the only warehouse of its kind in Germany[80], there is a logistics company, Hasenkamp Holding GmbH, which offers duty-free storage of art goods for an unlimited period of time in Berlin, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Cologne, Munich and Stuttgart[81], while Philoro is present in almost all large cities in the Federal Republic[82].

In Meiningen, Zentraldepot GmbH offers the storage of goods in shared or private warehouses, as well as a dedicated space for the exhibition of works[83]. Nicolas Perren, who as a Swiss is familiar with the controversial reputation of the Freeports, states that the Meiningen facility is a warehouse to which the customs authorities have access – everything by the book, then[84]. On 22 February 2022, Zentraldepot is pointed out as an example of opaque practices by MP Janine Wissler (Die Linke)[85]: in Germany, Wissler complains, there is no obligation for Freeports to register the actual owner of the goods, there are no time limits for storage, and transfer of ownership is allowed while the goods are in storage – which makes these places potential fodder for money laundering and tax evasion[86]. His denunciation occupied the pages of the newspapers for a few days, then nothing more. As for those financing Perren and Schulte, who with a total capital of not even € 100,000 allegedly bought a medieval villa, plus land for pensioners and who knows what else, this remains a secret.

United Kingdom and United States

The Delaware Freeport in Wilmington[87]

Great Britain hosted seven Freeports between 1984 and 2012, then decided to close them down due to the relevant laws passed by the European Union, which reduced the competitiveness of EU Freeports against international competition[88]. After Brexit, a debate started in the UK on the revival of Freeports, and in 2020 seven licences were granted: East Midlands Airport, Felixstowe and Harwich, Humber Region, Liverpool City Region, Plymouth, Solent, Thames and Teeside[89]. British legislation provides for a simple description of the property, excluding more detailed information[90]. While British and European laws explicitly mention the possibilities of laundering money through art deposited in Freeports, the London government makes no mention of this controversial aspect of Freeport development. Considering that the country is, together with China and the United States, one of the three largest art markets in the world (turnover is estimated at $12.7 billion, representing 20% of the global market[91])[92], London’s silence on the risks of Freeports is puzzling.

In the United States, where foreign-trade zones (FTZs) were established in 1934 to help boost production, trade and investment[93], there is a Freeport dedicated to the art world: the Delaware Freeport, a 3345-square-metre warehouse with plenty of space, top-level security, constant monitoring of the conservation conditions of the goods, a refined showroom[94], maximum confidentiality on the actual owners of the goods stored and exemption from paying customs duties[95]. Fritz Dietl, owner of the Delaware Freeport, opened the business in 2015, just as the scandal surrounding Yves Bouvier’s activities broke out, offering the many US collectors, gallery owners and art dealers a Freeport three hours’ drive from New York and two from Washington[96].

The success is overwhelming: in New York, one way to avoid paying customs duties on a work of art purchased at an auction is to entrust the shipping to the Freeport to the selling entity (the auction house in the example); in this way the buyer does not physically take possession of the good until it is inside the warehouse – avoiding assuming fiscal responsibility for the use of the work – where he can finally inspect it[97].

In February 2022, the US Treasury Department published a report entitled ‘Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art’, in which it emerges that the United States has also become aware of the danger posed by the vulnerability of the art market: the high value of many transactions, the frequent use of shell companies and intermediaries to buy and sell works, the culture of privacy and the complicity of professionals in the sector highlight the flaws in the American anti-money laundering system[98]. Freeports are explicitly mentioned in the report as potential vulnerabilities in the control system[99]. However, the report concludes with a series of non-binding recommendations[100]. In the short term, therefore, no concrete action will follow from these recommendations.

The humiliation of art

Edvard Munch’s painting ‘The Scream’, repeatedly stolen and later found in secret private collections[101]

Life for Freeports is not all sunshine and roses. Case in point is ARCIS, New York City’s first Freeport. Inaugurated in 2018, this windowless fortress, built in Harlem by the real estate giant Cayre Equities Llc[102], is equipped with the most sophisticated security systems: visitors must undergo iris scanning before entering the building, where they are subjected to further checks[103]. The installation of a technologically state-of-the-art storage facility in one of the world’s art capitals seems to herald a great success – costing $50 million[104]. But the high costs of using the facility are a boulder: Delaware is much cheaper[105]. On 2 September 2020 ARCIS closes its doors for good[106].

Even when they are not used to support criminal interests, such as South American drug cartels[107], or to evade tax payments, the artworks stowed in Freeports raise inevitable moral questions: artworks tend to deteriorate, and these warehouses are built to prevent this. All this, however, takes art away from its original purpose: to be admired. Paintings or sculptures from the 16th or 17th century have passed from hand to hand to rich families, and only rarely have been exhibited in a museum. Otherwise, they could only be enjoyed by the owner and his guests. The financialisation of art leads to works stored in Freeports no longer having any artistic value[108]. The uniqueness of the work and its invisibility are, for investors, the best guarantee for future appreciation[109].

But here we come to the main question: an artist does not live without selling, and every sale depreciates the work of art. This has been the case for millennia. Capitalism, with its rules of supply and demand, has made things worse: a painting has a value as fluctuating as grain or zinc, but linked not to the seasons and industrial use, but to the aesthetic sense of the time. And the age we live in, unfortunately, prides itself on humiliating and monetising beauty, joy, humanity, life.

[1] https://www.turismofvg.it/fvglivexperience/visita-al-municipio-di-trieste-per-i-300-anni-del-porto-franco

[2] https://www2.helsinki.fi/en/researchgroups/a-global-history-of-free-ports/about

[3] Max Karl Feiden, „Franz Haniel & Cie. GmbH“. Haniel, Duisburg 1956, pag. 3-21; Pacini, Giulia “The French Emigres in Europe and the Struggle against Revolution, 1789-1814”, French Forum No. 26, Paris 2001, pag. 113-115

[4] https://www.swissinfo.ch/ita/dossier-sulla-storia-del-contrabbando-tra-italia-e-svizzera/47237518 ; http://www.cicad.oas.org/cicaddocs/document.aspx?Id=3095

[6] https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/34

[7] https://swissgoldsafe.ch/de/weitere-informationen/leistungen-kunden-infrastruktur/zollfreilager/ ; https://philoro.de/filialen/zuerich ; https://swiss-safeguard.com/de/zollfreilager-zurich-flugahfen/

[8] https://philoro.de/filialen/virtuelle-filiale

[9] http://www.unionsverlag.com/info/title.asp?title_id=1357

[10] https://www.kendris.com/en/news-insights/2021/10/20/four-years-automatic-exchange-information-switzerland/#:~:text=Switzerland%20has%20implemented%20the%20global,has%20grown%20steadily%20to%20date

[11] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/panama-papiere-viele-bilder-werden-ueber-briefkastenfirmen-100.html

[12] https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/profile/lisa-paus/fragen-antworten/koennen-diese-zollfreilager-welche-zum-steuern-austricksen-und-zum-geldwaschen-benutzt-werden-koennen-nicht

[13] https://www.moneta.ch/zollbefreite-kunstaufbewahrung

[14] https://de.beincrypto.com/teil-i-interview-mit-analyst-walter-leonhardt-geldwaesche-freeports-und-scams/

[15] https://www.wayfair.com/decor-pillows/pdp/global-gallery-seated-man-leaning-on-a-cane-by-amedeo-modigliani-painting-print-on-wrapped-canvas-blga1881.htmlb

[16] https://www.ft.com/content/992dcf86-a250-11e4-aba2-00144feab7de

[17] https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/13/arts/design/art-proves-attractive-refuge-for-money-launderers.html

[18] https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/10010842

[19] https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/01/09/new-evidence-cited-in-restitution-claim-for-panama-papers-modigliani

[20] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/panama-papiere-viele-bilder-werden-ueber-briefkastenfirmen-100.html

[21] Oddný Helgadóttir, “The new luxury freeports: Offshore storage, tax avoidance, and ‘invisible’ art”, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 0308518X2097271. 10.1177/0308518X20972712, 2020, p. 3

[22] https://complianceconcourse.willkie.com/resources/anti-money-laundering-us-statute-of-limitations

[23] https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e934a7e1-a8ad-496b-a80b-568effc1a5e3

[24] https://iclg.com/practice-areas/anti-money-laundering-laws-and-regulations/switzerland#:~:text=1.7%20What%20is%20the%20statute,1%20lit.

[25] https://iclg.com/practice-areas/anti-money-laundering-laws-and-regulations/united-kingdom

[26] https://de.beincrypto.com/teil-i-interview-mit-analyst-walter-leonhardt-geldwaesche-freeports-und-scams/

[27] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-freeports-operate-margins-global-art-market

[28] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-freeports-operate-margins-global-art-market

[29] https://www.independent.co.uk/independentpremium/long-reads/bouvier-affair-yves-dmitry-rybolovlev-art-corruption-scandal-monaco-a9266561.html

[30] https://naturallecoultre.ch/en/about/

[31] Sam Knight, “The Bouvier Affair”, The New Yorker, 8 February 2016

[32] https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-38167501

[33] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/29/arts/design/one-of-the-worlds-greatest-art-collections-hides-behind-this-fence.html?_r=0

[34] https://www.swissinfo.ch/fre/des-tr%C3%A9sors-dans-des-entrep%C3%B4ts_ports-francs–les-coffre-forts-des-supers-riches/40487690

[35] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/27/arts/yves-bouvier-sells-his-geneva-based-art-storage-company.html)

[36] https://www.artrights.me/en/the-king-of-the-free-ports-yves-bouvier/ ; https://www.brookings.edu/essay/shanghais-dynamic-art-scene/

[37] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/le-freeport-west-bund-282939 ; https://www.dnb.com/business-directory/company-profiles.euroasia_investment_sa.45ab3b41fd994a233cdd1f934c766e59.html

[38] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/29/arts/design/one-of-the-worlds-greatest-art-collections-hides-behind-this-fence.html?_r=0

[39] https://www.reuters.com/article/uralkali-idUSLDE65D05U20100614

[40] https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/as-monaco-dmitry-rybolovlev-and-his-influence-in-monaco-a-1238822.html

[41] https://www.artnews.com/art-collectors/top-200-profiles/dmitry-rybolovlev/

[42] Sam Knight, “The Bouvier Affair”, The New Yorker, 8 February 2016

[43] https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/as-monaco-dmitry-rybolovlev-and-his-influence-in-monaco-a-1238822.html

[44] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/15/arts/design/leonardo-da-vinci-salvator-mundi-christies-auction.html

[45] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/06/world/middleeast/salvator-mundi-da-vinci-saudi-prince-bader.html

[46] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/dmitry-rybolovlev-yves-bouvier-366572

[47] Alexandra Bregman, “The Bouvier Affair: A True Story”, Alexandra Bregman, 2019, p.178

[48] https://www.davideferro.com/blog1/2021/9/26/cratere-di-eufronio-con-scene-di-palestra

[49] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/yves-bouvier-declares-total-victory-dmitry-rybolovlev-2010315

[50] https://inews.co.uk/culture/arts/how-argument-450m-da-vinci-painting-exposed-grubby-world-art-dealing-1048872

[51] https://delano.lu/article/bouvier-on-the-rebound-freepor

[52] https://newrepublic.com/article/147192/modern-art-serves-rich

[53] https://itsartlaw.org/2020/11/03/behind-closed-doors-a-look-at-freeports/

[54] https://traffickingculture.org/encyclopedia/case-studies/giacomo-medici/

[55] https://traffickingculture.org/case_note/euphronios-sarpedon-krater/

[56] https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/19/arts/design/19bowl.html

[57] Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini, “The Medici Conspiracy”, Public Affairs, 2007, p. 19

[58] Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini, “The Medici Conspiracy”, Public Affairs, 2007, pp. 19-20

[59] Vernon Argento, “The Lost Chalice”, HarperCollins, 2009, pp. 180-81

[60] Vernon Argento, “The Lost Chalice”, HarperCollins, 2009, pp. 175-76

[61] Vernon Argento, “The Lost Chalice”, HarperCollins, 2009, p. 192

[62] Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini, “The Medici Conspiracy”, Public Affairs, 2007, p. 107

[63] https://www.adnkronos.com/Archivio/AdnAgenzia/2005/11/15/Cronaca/ARCHEOLOGIA-CASO-MUSEO-GETTY–GIACOMO-MEDICI-SPERO-NEL-PROCESSO-DAPPELLO_091951.php ; https://www.civonline.it/2012/05/30/traffico-di-reperti-archeologici-condannato-giacomo-medici/

[64] https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/news/2009/it-s-business-as-usual-says-freeport-as-eu-brings-law-change-in-geneva/

[65] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/zollfreilager-in-meiningen-banksafe-fuer-grosse-kunst-100.html

[66] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/trove-looted-antiquities-belonging-disgraced-dealer-robin-symes-found-geneva-freeport-418157

[67] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/switzerland/12134541/Disgraced-British-art-dealers-priceless-treasure-trove-discovered-hidden-in-Geneva.html

[68] https://news.artnet.com/market/switzerland-freeport-regulations-367361

[69] Katie L. Steiner, “Dealing with Laundering in the Swiss Art Market: New Legislation and its Threat to Honest Traders”, 49 Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 351 (2017), p. 368

[70] “Message concernant la modification de la loi sur les douanes”, FF 2015, p. 2667

[71] https://money.cnn.com/2014/04/08/news/economy/freeports-art-luxury/index.html?iid=EL

[72] https://www.economist.com/briefing/2013/11/23/uber-warehouses-for-the-ultra-rich

[73] https://news.artnet.com/market/delaware-freeport-tax-haven-341366

[74] https://www.welt.de/kultur/article166951654/Deutschland-bekommt-sein-erstes-Zollfreilager-fuer-Kunst.html

[75] Monika Roth, “Kunst und Geld – Geld und Kunst: Schattenseiten und Grauzonen des Kunstmarkts”, Stämpfli Verlag, 2020, p. 196

[76] Vallor Development GmbH Berlin

[77] Peter Bitschin on Nexis

[78] Meta Holding GmbH Davos

[79] 2021.06.05 Neuer Wohnraum für Senioren

[80] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/zollfreilager-in-meiningen-banksafe-fuer-grosse-kunst-100.html

[81] https://hasenkamp.com/de/fineart/kunstlagerung

[83] https://www.zentraldepot.de/depots ; https://www.welt.de/kultur/article166951654/Deutschland-bekommt-sein-erstes-Zollfreilager-fuer-Kunst.html

[84] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/zollfreilager-in-meiningen-banksafe-fuer-grosse-kunst-100.html

[85] https://www.linksfraktion.de/fraktion/abgeordnete/profil/janine-wissler/

[86] https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/profile/janine-wissler/fragen-antworten/koennen-diese-zollfreilager-welche-zum-steuern-austricksen-und-zum-geldwaschen-benutzt-werden-koennen-nicht

[87] https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/delaware-freeport-fine-art-storage

[88] Matthew Ward, “The establishment of free ports in the UK”, House of Commons Library, October 2018, p.3

[89] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/mar/03/eight-free-ports-low-tax-zones-created-england

[90] https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/freeports-consultation/freeports-consultation#chapter-3-customs chapter 3

[91] Clare McAndrew, “The Art Market 2020”, Art Basel & UBS Report, 2020, p. 29

[92] Clare McAndrew, “The Art Market 2020”, Art Basel & UBS Report, 2020, p. 19

[93] Liana Wong, “U.S. Foreign-Trade Zones: Background and Issues for Congress”, U. S. Congressional Research Service, December 19th 2019, p. 7

[94] https://www.delawarefreeport.com/what-we-do

[95] https://www.barrons.com/articles/freeports-in-freefall-1448897379

[96] https://www.barrons.com/articles/freeports-in-freefall-1448897379

[97] https://news.artnet.com/market/delaware-freeport-tax-haven-341366

[98] “Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art”, Department of the Treasury, February 2022, pp. 19-25

[99] “Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art”, Department of the Treasury, February 2022, p. 18

[100] “Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art”, Department of the Treasury, February 2022, p. 30

[101] https://www.thevintagenews.com/2018/03/06/valuable-stolen-paintings/?firefox=1

[103] https://news.artnet.com/market/the-first-ever-freeport-in-new-york-is-a-super-high-tech-art-warehouse-1275194

[104] https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/09/03/manhattans-first-and-only-freeport-to-close

[105] https://news.artnet.com/market/the-first-ever-freeport-in-new-york-is-a-super-high-tech-art-warehouse-1275194

[106] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-02/fortress-in-new-york-storing-million-dollar-art-to-shut-down?sref=NZW35ECu

[107] https://www.economist.com/briefing/2013/11/23/uber-warehouses-for-the-ultra-rich

[108] https://www.unclosed.eu/rubriche/sestante/esplorazioni/131-freeport-art.html

[109] https://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60521/freeportism-as-style-and-ideology-post-internet-and-speculative-realism-part-i/

Leave a Reply